Lee Anne Bell is professor emerita at Barnard College, Columbia University. She specializes in the study of gender, race, and culture in educational settings, and how these issues impact equity, access, and opportunity in schools. Bell’s work also focuses on teaching race and racism through storytelling and the arts, and in the early 2000s she worked with a team of artists, academics, public-school teachers, and undergraduates to develop an anti-racist storytelling curriculum that was implemented in two New York City classrooms. Called the “Storytelling Project: Learning about Race and Racism Through Storytelling and the Arts,” the research project led to the development of the Storytelling Project Model, which is described in Bell’s book, Storytelling for Social Justice: Connecting Narrative and the Arts in Antiracist Teaching. Bell is also a co-editor of Teaching for Diversity and Social Justice, and she produced 40 Years Later: Now Can We Talk?, a documentary film that explores the impact of racial integration in the Mississippi Delta through dialogue with black and white alumni of the 1969 graduation class of South Panola High School in Batesville, Mississippi.

Interview by Stephen Abbott

Q: I want to begin with the Storytelling Project. Can you tell us about the origins of the project, how it worked, and what your team learned from the process and research?

Well, I had just joined the faculty at Barnard College as the director of the education program, and the development office introduced me to a potential funder. We went out to lunch, and he asked me a question that’s probably the best question I’ve ever gotten in my life: “If you had the money, what would you want to do with it?” I told him about my past work, and my interest in teaching about race and racism, and that I had recently co-edited a book called Teaching for Diversity and Social Justice with Maurianne Adams and Pat Griffin.

At the time, I was interested in doing something new, but I wanted to continue exploring the same topic. I had just seen a performance created by Michelle Fine at the CUNY Graduate Center based on her work with a group of young people and artists. The performance honored the 50th anniversary of Brown vs. Board of Education, looking back at the Brown decision a half-century later. It was really exciting to see the way Fine and her team used the arts to work with young people in her retrospective.

So when the funder posed this great question, I said, “I’d really like to work with a team of artists, teachers, academics, and some of my undergraduate students and take a new look at the teaching of race and racism to see what we can come up with if we pool our various talents, skills, and interests.” We talked back and forth about what such a project might look like and what kind of funding I would need, and he ended up funding it.

I wanted to find a workspace that would take us out of our daily routines, and the funder had a great space in a beautiful old brick building in the Dumbo neighborhood of Brooklyn. It was an airy, open space on the top floor of the building with art on the walls and views from every window of the river and bridges to Manhattan. The team I assembled decided to meet there once a month.

One important thing about having money on a project like this is that we were able to compensate people who are usually not paid very well, like artists and teachers, and we were able to cover transportation and food costs. For the teachers who participated, we also paid for substitutes if they had to miss a day of classes.

One of the people who joined us was my post-doc, Rosemarie Roberts, a dancer and dance teacher who had also worked on the project with Michelle Fine. Rosemarie and I worked together to organize everything. She knew a poet, Roger Bonair-Agard, and he joined us. I also knew Kayhan Irani, a performance artist, and she joined us as well, along with photographer Uraline Septembre Hager.

I also knew some academics who were working with young people in interactive ways: Dipti Desai from New York University, who is the director of the art education program there, and Thea Abu El-Haj from Rutgers University who had been doing work with Palestinian-American and Jewish youth in the United States. I thought their work was really interesting. We also found three incredible teachers—a high school teacher, Christina Glover, and two middle school teachers, Anthony Asaro and Patricia Wagner. Three of my undergraduate students rounded out the team: Zoe Duskin, Vicki Cuellar, and Leticia Dobzinski.

On the first day we convened in Dumbo, we started discussing our interests in the topic and what we each brought to the project. Right away, the artists got us up and moving around and interacting with each other and with the material, and it was just a great community-building process.

From that day forward, that was basically the process we used every time we got together. Different members of the team would take responsibility for organizing some part of the day in ways that reflected their particular background or expertise. For example, Thea had everyone do some reading and writing work based on Toni Morrison’s Nobel Prize speech. At another session, Dipti shared some contemporary art to show us how artists are challenging racism through their work. Each day was generative and inspiring.

We met for a year, and we were taking notes throughout, and Rosemarie, myself, and the Barnard students would cull through the notes following each meeting. As part of the project, we read about critical race theory, which looks at storytelling and counter-storytelling as a process for seeing the ways in which mainstream studies ignore race and exclude the concerns of people of color. We liked the idea of “counter-storytelling,” and started using that concept in our work. We realized we were hearing different kinds of stories, and a few common story types began to emerge over the course of our meetings—that’s more or less how we came up with the model.

Once we developed a draft of the story types, and began creating curriculum activities around the types, we brought in some high school students as paid consultants because we wanted to know how young people responded to the emerging ideas we were playing with. Because adults don’t usually think of high school students as consultants or experts who have something to valuable to say, it was a particularly fun and illuminating element of the project. The students were extremely thoughtful and provided a lot of useful insights. They talked to us about how they experienced racism in their schools and which stories and story types resonated with their experiences.

At the end of the yearlong project, we held a five-day summer institute with New York City public school teachers, which also contributed insights that eventually ended up in the book. By actually doing our activities with teachers, we learned a lot about what worked or didn’t work, and what kinds of support teachers need to apply the Storytelling Project Model in their own classrooms. In the second year of the project, we field-tested the curriculum in two high school classrooms in the Bronx, and we again solicited feedback from the teachers and students in these classes. Four Barnard students—Svati Lelyveld, Brett Murphy, Vanessa D’Egidio, and Ebonie Smith—attended all of the classes to take notes, and they participated in the data analysis as we finalized the curriculum.

One major takeaway I had from the project is how invaluable the arts can be in generating clear thinking and new ideas. Everyone working on the project had developed intellectual ideas about racism, and we all had individual experiences with racism that we brought to the table, but writing poetry together or looking at contemporary art or doing theater of the oppressed activities allowed us to enact abstract concepts like power or oppression or liberation. Physically engaging with each other, and trying to embody what those ideas might look like, really helped us think more deeply about what we were reading or discussing. I should also mention that Maxine Greene was an inspiration throughout our work together and was an interested observer and supporter as we developed the project.

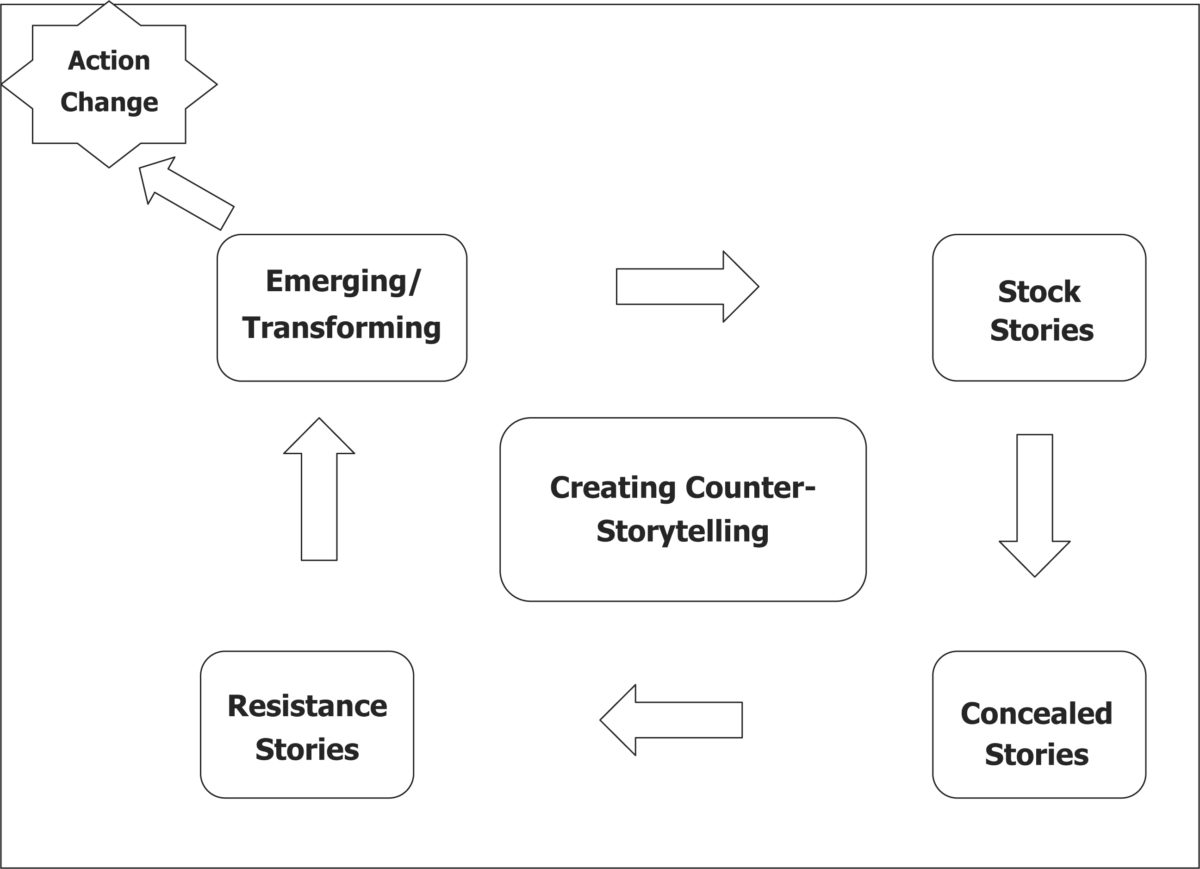

Q: You alluded to this already, but the central organizing feature of the Storytelling Project Model is its articulation of four distinct types of stories, and how each type can be used to illuminate different dimensions of America’s complex history of race, including the personal narratives of those who have been harmed the most by racism. I think it would be helpful if you briefly described each of the four story types, but perhaps we should focus primarily on stock stories. What are stock stories and how do they operate in American culture?

Stock stories are cultural narratives that valorize, reinforce, justify, or rationalize the racial status quo. They’re the stories that communicate this is just the way things are, this is the way things should be, or this is what’s normal and acceptable—they’re normalizing statements that justify inequality.

Stock stories are reflected in what people commonly say about who we are as a country, but they are incomplete, misleading, and often false stories, such as assertions that we live in an egalitarian democracy that’s welcoming to immigrants, or that everyone can achieve the American dream if they just work hard enough. These kinds of stock stories justify the status quo, so in our analysis we start with stock stories because they form the backdrop for the other story types.

What we uncovered during the Storytelling Project were a multitude of other stories that have been eclipsed by the stock stories. These alternative stories narrate a much different story about the immigrant experience or the ability to get ahead through hard work. We call these stories “concealed stories” because they have been left out of our collective history and they remain largely untold and unheard, even to this day. Concealed stories are often told by people in communities of color who have struggled to be fully included in society or who have been left out of the so-called American dream. These alternative stories challenge the mythology of our stock stories, whether it’s their veracity or their representation of history. At the very least, they expose the partiality of stock stories—that they don’t convey the whole truth, and that more needs to be unearthed and examined, particularly regarding race and racism in the United States.

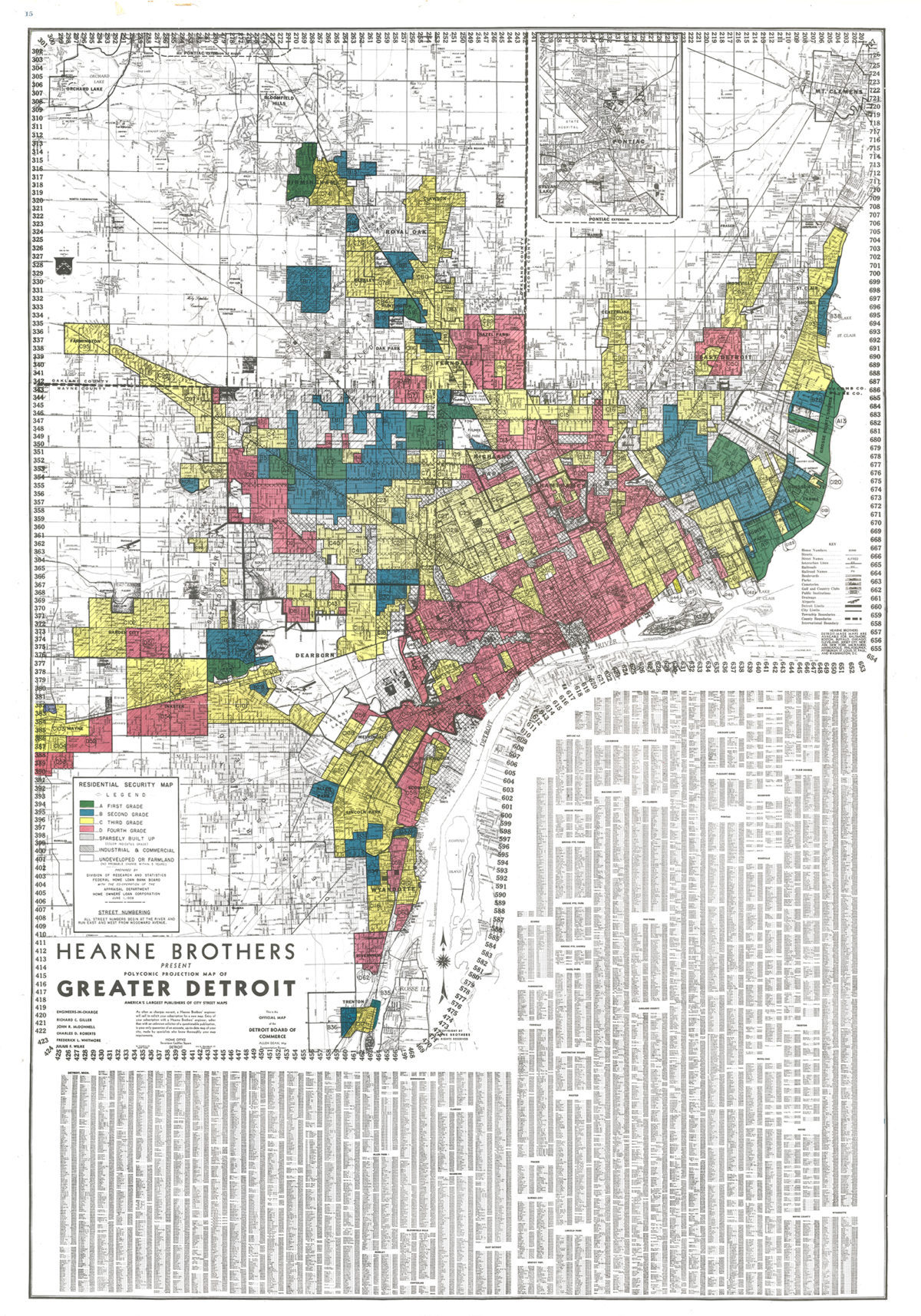

For example, concealed stories from people in marginalized groups reveal the barriers to getting ahead through hard work promised by the American dream stock story. Such concealed stories illustrate the effects of redlining, segregation, or employment discrimination that prevent people of color from building equity and assets that they can pass on to the next generation. In my book, I provide some of the statistics behind these concealed stories.

It’s important to point out that when we’re talking about any of these story types, we’re not talking about individual or idiosyncratic stories. These are stories that echo throughout our history and our culture. Some of the specific stories may appear to be individual or idiosyncratic, but they all reflect broader patterns and narratives in our culture and society.

For example, when a white person complains about affirmative action by saying, “Well, my uncle or cousin or brother didn’t get a job because it was given to a less-deserving minority,” something that’s usually impossible to verify, well, that’s an individual story that’s also representative of a stock story that gets repeated over and over—it’s part of a much broader narrative pattern that’s attempting to challenge the validity of affirmative action.

“Resistance stories” are the third type of story, and they’re the often-forgotten stories from our history that challenge the whitewashed, selective, and stock versions of American history that so many of us learned in school. It’s getting better now, of course, but schools are still teaching histories that largely or entirely exclude the experiences and perspectives of African Americans, Native Americans, other people of color, as well as the stories of white people who fought against racism.

Throughout American history, there have been people who’ve resisted racism and fought against it—people from all racial groups—but we typically don’t learn about, or know very much about, their stories. Yet these stories of resistance can inspire us today because they give us models and inspiration and a fuller and more accurate picture of American history.

For example, we learn very little about how groups have organized to fight for justice at various points in American history. In the long and ongoing struggle for civil rights, we typically learn a sanitized version of the real story, such as the popularized story of Rosa Parks as an individual woman who was tired one day and refused to move to the back of the bus. We don’t learn about Rosa Park’s committed activism, the organized resistance of black churches and other organizations, the thousands of ordinary black citizens in Montgomery who walked for an entire year rather than take segregated busses, or the small but important number of white allies who volunteered to drive people to work.

The final story type is called “emerging-transforming stories,” and we create these stories in the present moment as we build on what we’ve learned studying the stock, concealed, and resistance stories. Emerging-transforming stories acknowledge that we are not separate from history, that we step into the stream of history, and that we have a role to play in either supporting or challenging injustice through our everyday actions. These stories interrupt and dismantle the old racist narratives and replace them with new narratives that can redefine how we all relate to one another, what we mean by community, and how we can create a society that is fair and inclusive.

Q: As you just said, the “emerging” or “transforming” stories are what will ultimately help us create new narratives that can rewrite our understanding of race and racial dynamics. You’ve called this process a “counter-storytelling community” because it intentionally challenges the stock stories that have long perpetuated and reinforced racist mythologies. What does a counter-storytelling community typically look like in practice?

Yes, the creation of counter-storytelling community is a central feature of the Storytelling Project Model, and it happens when people engage in groups and communities to talk about issues of racism and learn from each other. If we want to challenge the stock stories that just keep getting repeated and replicated, we need to intentionally and explicitly create a different kind of community, one in which issues of race and racism can be held up and examined honestly, and in which we can all face the pain of racism and acknowledge the role that we and other members of our racial group have played in that history.

Building a counter-storytelling community requires people to make certain commitments, and they often need ground rules and guidance to create communities that operate consciously to challenge racism. For example, problematic patterns of behavior need to be called out and addressed, such as white people expecting or asking people of color to educate them about racism, which is a very typical behavior in dialogues on race.

Many white people assume that people of color possess all the knowledge about racism, but they overlook the fact that certain experiences with racism also need to be seen and understood from the perspective of white privilege and dominance, and that those experiences operate in ways white people can expose from the inside. When these kinds of behaviors happen, everyone participating in the community needs to hold it up and talk about it so that a different kind of dialogue can take hold. That’s one example of building counter-storytelling community.

“Many white people assume that people of color possess all the knowledge about racism, but they overlook the fact that certain experiences with racism also need to be seen and understood from the perspective of white privilege and dominance, and those experiences operate in ways white people can expose from the inside. When these kinds of behaviors happen, everyone participating in the community needs to hold it up and talk about it so that a different kind of dialogue can take hold.”

Another essential feature of a counter-storytelling community is that people need to be willing to hang in there, to be challenged, to hear truths they might not want to hear, and to listen carefully to what other people have to say. As I mentioned, most people have rarely if ever experienced this kind of dialogue, so they usually need guidance, ground rules, facilitation, and forms of support—otherwise, it’s not going to work.

Another essential element of counter-storytelling is a collective imagining of what could be. What kind of communities do we want to have? And what’s required to make that happen? What kind of a society do we want to be? What does a multi-racial democracy look like? How do we bring it into being? How do we protect and sustain it? How do we continue to perfect it?

In the graphic we developed for the Storytelling Project Model, there’s an arrow that leads to action and change after going through all the story types, but there’s also an arrow pointing back to stock stories because we can always get co-opted back into racism, into the status-quo system, so we have to be vigilant.

Read the Organizing Engagement introduction to the Storytelling Project Model →

For example, until LGBTQ people started talking about their experiences, until their stories started being told, society largely didn’t acknowledge them, even in progressive political circles. People with disabilities were also largely ignored—that’s another example. Well, how do all these issues affect them? What changes do we need to enact to fully include them? Storytelling helps us continually learn who’s being left out. We continually learn what we didn’t know before, and what we need to know to keep perfecting how we’re going to function as an inclusive, multi-racial democracy.

I realize that I might sound idealistic, but the only alternative I see is just a constant fighting against ignorance and meanness and hatred and belligerence, which is exhausting and dispiriting. I believe we need positive visions to sustain us and remind us what we are fighting for. These stories help us hang in for the long haul.

Q: Have you encountered any particularly successful real-world examples of counter-storytelling?

Oh, yes. In practice, a counter-storytelling community can take a lot of different forms. One larger-scale example is the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama. The memorial project is creating a counter-storytelling community by engaging visitors in a visual walking tour of lynching and racism that helps people question their and our role in United States history. It is an inspiring and critically important place that I believe every person in this country should visit and learn from.

On a smaller scale, an example that comes to mind is the work of Susan Glisson, one of the contributors to the new edition of Storytelling for Social Justice. Glisson is an activist and trainer in the American South who has used the Storytelling Project Model in her work. I met her when she was living and working in Mississippi, but I believe she works with communities all across the country, especially on racial tensions in community policing.

Glisson says in her essay that having people tell their stories is a method she often uses, but getting them to take the next step was always challenging. The four story types in the model helped her figure out how to move groups forward by examining concealed and resistance stories in their communities as a basis for taking action in the present. I think she’s doing really great work.

I’ll mention another example. I’m reading a book that just came out by Jonathan Metzl called Dying of Whiteness: How the Politics of Racial Resentment Is Killing America’s Heartland. Metzl is a professor at Vanderbilt University, and in the book he looks at three different states and the ways that racial resentment affects how white people respond to different issues in each state: gun rights, healthcare, and education. What his research shows is how racial resentment on the part of whites ends up generating policies that often hurt whites even more. For example, he looks at gun control in Missouri. Apparently, the state used to have pretty strong gun protections—people had to go down in person to the local sheriff’s office to get a gun permit, they had to have a secured storage locker for their gun, and they had to take a class in firearms use and safely.

“The white racial resentment driving state politics and policies are hurting white people as much or more than people of color. In one sense it’s hard to believe, but pitting racial groups against one another has been a consistent theme throughout our history. By exposing the self-destructiveness of white racial resentment, Metzl is telling an important counter-story.”

But then conservative groups like the Tea Party came in and part of their message was aimed at stoking racial fear—that you need guns to project your family from black people. Keep in mind that we’re talking about Missouri, where most people live in all-white communities, right? Well, now Missouri has some of the laxest gun-control laws in the country, and the suicide rate has skyrocketed in the state. And who’s most affected by this problem? It’s young white men.

Metzl also looks at the healthcare system in Kentucky and the education system in Iowa. And in these cases, as well, the white racial resentment driving state politics and policies are hurting white people as much or more than people of color. In one sense it’s hard to believe, but pitting racial groups against one another has been a consistent theme throughout our history. By exposing the self-destructiveness of white racial resentment, Metzl is telling an important counter-story.

In the emerging-transforming story chapter of the book, I also write about the Black Lives Matter movement, the Dakota Access Pipeline protests, the DREAMers, and the Parkland students because these emerging-transforming stories show us what’s possible, and because they’re all grounded in a knowledge of history and use acts of intentional storytelling to imagine what is possible in fighting toward a more just society. What’s inspiring about these movements is not just a consciousness of history, but they are using resistance and concealed stories—even if they don’t use those terms—to ground and drive the emerging-transforming stories they’re creating.

What emerging-transforming stories really highlight and show us is that dialogue, collaboration, coalition-building, and working for the common good can provide the inspiration we need to move forward. We can’t just react to the horrors; we also have to articulate and co-create a vision of the society we want to motivate us to move toward.

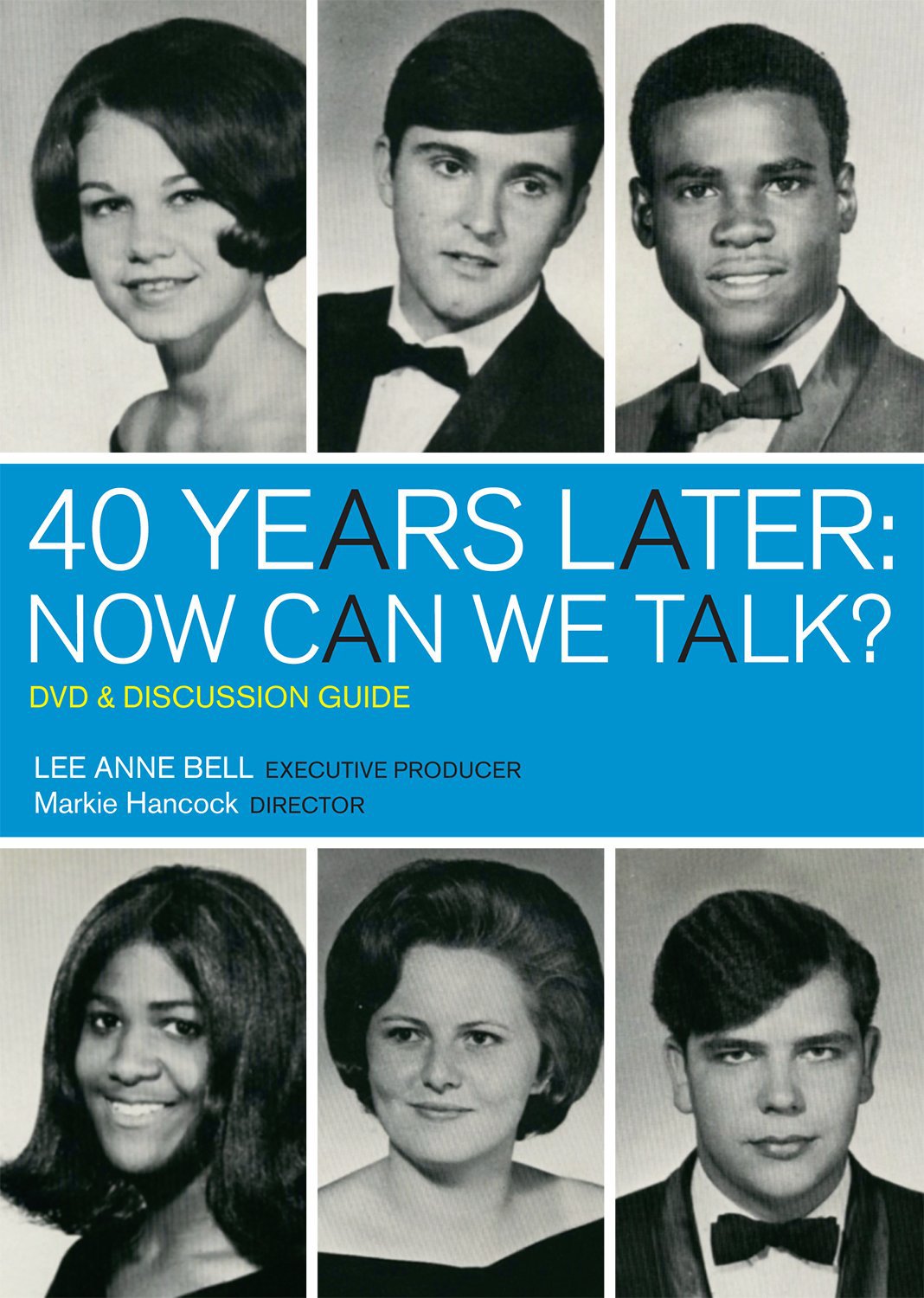

Q: It seems appropriate to end this interview with a story. After the first edition of Storytelling for Social Justice was published, African American woman from the Mississippi Delta contacted you. It turned out that this woman had graduated from high school in 1969, but she and her fellow black classmates were not invited to their high school reunion until 2009. Your work with her eventually developed into a documentary film called 40 Years Later: Now Can We Talk? How did the project evolve and what happened over the course of filming these conversations? Can you talk a little about the role that storytelling can play in racial healing and reconciliation more generally?

I had a website for the Storytelling Project, and a woman named Cheryl Johnson from North Carolina found the website, and called me one day in 2009. She was hoping I could help her with a storytelling project, and I said, “Sure. Tell me about it.” The story she told me was incredible. She and her other black classmates had just received an invitation to their high school reunion for the first time in 40 years! They had never before been invited to a reunion. Cheryl said she realized that she and her fellow black classmates had never actually talked to one another about what had happened to them back then, and they very much wanted to have that conversation. She wanted to know if I would facilitate it. That’s pretty much how it started.

I said I would be happy to facilitate, and also somewhat naively added, “This seems like a historic opportunity—we should probably film this.” She said, “Well, let me talk to the others and see how they feel about that.” At the time, I was imagining someone holding a video camera in the corner—I wasn’t thinking about professionally filming a documentary. But I spoke with my friend Markie Hancock, who’s a filmmaker, and she said, “You know, if you’re going to do this, you should do it right, and you need high-quality equipment and filmmaking skills from the beginning—a camcorder isn’t going to work.”

Cheryl talked to the other people, and they agreed to be filmed. Barnard College gave me some money so that I could bring a camera person, Claudia Raschke-Robinson, to Mississippi, and we hired a sound person from Memphis, as well. I also brought my colleague Fern Khan to co-facilitate our first meeting. Initially, the goal was simply to film the discussion so we wouldn’t lose what came out of that day.

We met at a community center in a black neighborhood in Batesville, Mississippi—the town where the reunion took place—and we spent about eight hours together. The opening prompt was simply, “Just start with what you remember….” That was the only prompt they needed. Everybody started their stories with “I remember…” and the conversation just rolled on from there.

What came out were really painful, horrible stories about how they were treated by white students, teachers, coaches, and administrators. Stories about the complete lack of support they felt in school and what it was like to want to learn but be denied that opportunity. For example, in one of their science classes, the teacher put them in a corner and taught only the white students on the other side of the room. The stories were amazing, really poignant, and truly painful to hear.

But for them, it was cathartic—they were finally able to share these stories and realize they weren’t alone. They had decided to attend the reunion after all, and I requested permission to join them. The reunion committee said I could come, but I couldn’t bring the camera crew or anyone else. I ended up attending with the black alums, and it was fascinating to see the first awkward attempts on the part of the white alums to welcome their black classmates.

The white man who opened the gathering said something vague about it being a historic moment and offered a few words of welcome, but then the reunion went on as I’m guessing it had every year previously. At one point, they even showed a slide show of photos from their high school years and all the pictures were white kids. It seemed that, after that one moment of welcome, it was the same white reunion it had always been.

“I don’t think racial reconciliation can happen without people owning up and taking responsibility for the past, but we also need to keep owning up and taking responsibility going forward. We always have to ask ourselves, ‘Now what? Now that we’ve had the conversation, how is that going to change what we do next?'”

I talked to the organizers, and said, “We had a discussion today with the black alumni about their experiences in high school, and I’m wondering if you would be willing to have a conversation, as well.” They were a little suspicious, but I stayed in touch with them over email after I returned to New York, and they eventually agreed to have the conversation and got a group of people together. I went back down Batesville with the film crew, and we spent a day together, starting our discussion with the same prompt I used in the first conversation: I asked them what they remembered, and they started talking about their memories.

After that second conversation, we brought the two groups together for a joint conversation, something members of both groups said they would like. In that third gathering, we showed film clips from each of the separate conversations. These illustrated two very different sets of experiences, and we filmed their reactions and responses to these clips. I think that approach jump-started a more honest conversation than might typically happen in such a meeting, even though it didn’t go as far as I had hoped it would. I think the film illustrates the challenges and possibilities of cross-race dialogue.

In terms of racial reconciliation, I would say the film is instructive but does not pretend to be an ideal model. The film does show the very different experiences white people and black people can have even when sharing the same space. It also illustrates the importance of apology, and the fact that apology is meaningful. But I think that apologies are not enough—true reconciliation also requires taking responsibility and owning up to the past, and it requires some corrective action going forward. I don’t feel those second two steps happened, although there was a moment of apology that the black alums appreciated, as I mentioned.

I have shown the film in many venues around the country and it does generate productive conversation about ongoing racism today, especially in terms of school segregation, and it helps to show some of what’s needed for racial reconciliation to occur. While the film does not enact a full process of reconciliation, it shows what happens in an unscripted dialogue that we can all learn from.

For me, the Storytelling Project Model is useful because it can help people create a holding environment in which they can tell their stories and have their stories heard in a respectful way. And because it helps ground dialogue in history, it can connect individual stories and traumas to the broader patterns of our shared history. It also asks people to carry the conversation forward—to not just listen to stories and tell stories, but to question what these stories mean for us as individuals, as communities, and as a nation and to consider the steps we need to take to enact the kind of country we want to see.

I don’t think racial reconciliation can happen without people owning up and taking responsibility for the past, but we also need to keep owning up and taking responsibility going forward. We always have to ask ourselves, “Now what? Now that we’ve had the conversation, how is that going to change what we do next?”

It’s always that next step—taking action—that’s essential.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Copyright

Copyright © by Organizing Engagement and Lee Anne Bell. All rights reserved. This interview may not be reproduced without the express written permission of the publisher. Brief quotations are allowed under Section 107 of the Copyright Act.