Mark Warren is a professor of public policy and public affairs at the University of Massachusetts Boston’s McCormack Graduate School. Warren studies how broad-based alliances, grassroots organizing, and multiracial political action can advance social and educational justice in American communities and schools. He is the author of several books, including Fire in the Heart: How White Activists Embrace Racial Justice and Dry Bones Rattling: Community Building to Revitalize American Democracy, and he is co-author, with Karen Mapp (@karen_mapp), of A Match on Dry Grass: Community Organizing as a Catalyst for School Reform, which describes the results of a large-scale study of the role community organizing plays in school reform. Warren is also a co-founder of the Urban Research-Based Action Network, and he is committed to using scholarly research to promote greater equity in public policy, democratic practice, and educational decision-making. His most recent book, written in collaboration with the journalist David Goodman (@davidgoodmanvt) and the book’s many contributors, is Lift Us Up, Don’t Push Us Out! Voices from the Frontlines of the Educational Justice Movement.

Follow Mark Warren on Twitter → @mark_r_warren

Interview by Stephen Abbott

Q: In Lift Us Up, Don’t Push Us Out!, you write, “Many Americans, especially white Americans, cling to the notion that public education represents a path for children of color to access the American Dream. They hold up individual success stories and applaud the hard work that created achievement. Yet the essays in this volume show that individual successes remain the exception to the rule. The harsh reality is that public education is part of a larger system that systematically denies opportunity to youth of color and keeps their communities without power.” What would you say to people who simply don’t believe the American public education system perpetuates and reinforces discrimination in communities and society? And can you give us a real-world example of the problem?

For a lot of people, particularly more affluent white Americans, their children are going to well-resourced public schools that are embedded in communities with a lot of support and with highly qualified teachers teaching a curriculum that’s relevant to their lives. These families typically don’t have any direct experience with the kind of education that children from low-income communities of color—particularly African American and Latino students—experience, and therefore they don’t have a real understanding of the obstacles, indignities, or violence these students face.

For example, schools in low-income communities of color are significantly under-resourced; their teachers, while often very caring, are less qualified; students are learning in older, often dilapidated buildings with outdated materials; and the curriculum being taught has very little content that relates to the history, culture, and experiences of African American or Latino communities in the United States. These students also face daily policing in their schools and very harsh zero-tolerance discipline systems. All of which leads to what we call the school-to-prison pipeline.

Let me give you an example that I write about in the book. I’ve been touring the country interviewing people and doing research on the school-to-prison pipeline, and there are some very devastating personal experiences I’ve observed. When I was in a community outside of Richmond, Virginia, I met a mother who was called into a school meeting, and I got the chance to go along with her. This woman’s son, an African American boy in middle school, was a special-education student, and he had what’s called an IEP—or an individualized education plan. The plan stated that he was allowed to go outside during the school day to blow off steam, essentially.

The day before the meeting, he went outside on school grounds for just that purpose, and a security guard came up to him, handcuffed him, and dragged him along the ground. When he got home, his clothes were completely full of mud, and his mother was outraged. The school did not suspend him, which would’ve put it on record—it would have created a paper trail. Instead, they called the mother and told her she should keep him home for a few days. When she went to the meeting the next day, nobody apologized for the fact that her child had been assaulted. They also had a video of the assault, which they had been watching, but they refused to show it to her. In the end, she had to settle for getting $100 to buy her son some new clothes.

These kinds of violence and assault cases are quite numerous. We have statistics that show these patterns, but we also have the individual stories of black and brown students and their families describing what they are experiencing in our public education system today. While people need to know the statistics, of course, they are ultimately just numbers. I really think what people need to hear are the individual stories about what’s happening to real people in American public schools. And that’s why in our book, Lift Us Up. Don’t Push Us Out!, we feature essays by people who tell their personal stories. We have black and brown parents and students telling their stories, as well as a range of people who are working with them to organize and change these systems.

Q3: Many Americans are simply unaware that there’s a school-to-prison pipeline in American public education because, as you mentioned, their children have not experienced abusive school-discipline practices or they have not seen first-hand the resulting long-term harm that can result from systemic school pushout. What is the school-to-prison pipeline, how does it work, and why does it urgently need to be dismantled?

The school-to-prison pipeline refers to a systemic problem that disproportionately affects students in low-income communities and communities of color. It often begins with zero-tolerance discipline, where children, and particularly black and brown children, are suspended and often expelled for minor behavioral infractions. Once they’re expelled, they’re not in school learning, and they’re often out on the streets where they get caught up in the juvenile criminal-justice system—that’s the pipeline. And I’m not talking about small numbers of children and youth. Take Texas, for example. In that one state, 75% of all black children have been suspended from high school, as one recent study showed. Nationally, black children are three times more likely to be suspended than white children.

If a student is suspended, and eventually drops out or is pushed out of school, these experiences often have devastating lifelong effects on young people. If you are a young black man without a high school degree, you are highly likely to end up in the criminal justice system. In fact, another study showed that nearly 70% of all black men without a high school degree end up in prison at one point in their lives. That’s just a devastating number. Or we could look at it in terms of college completion rates. Even in a city like Boston, which claims to have one of the best big-city public education systems, a child entering one of the city’s non-exam high schools today has about a 12% chance of graduating from high school and then completing college within six or seven years. Just over half will graduate from high school. Of that number only half will even start college, and of that number only half will actually finish.

Think about that number: 12%. If you’re poor, if you’re a black or brown child, if you’re in an underfunded school, our public education system is failing you. It just is. It’s reinforcing the profound inequities that exist in our society. These children are most likely to remain in poverty or end up in the prison system.

Maybe ten years ago, most Americans—and even most people in the education field—had never heard the term “school-to-prison pipeline.” It turns out that the first people who started calling out the school-to-prison pipeline, and who gave it a name, were black and brown parents and students in communities across the country. I’ve been down to the Mississippi delta, and I went to Holmes County, which is very poor—it’s one of the poorest counties in the country—and I visited a local organization that’s connected to Southern Echo (@SouEcho), a community-organizing group. In Lift Us Up, Don’t Push Us Out!, Joyce Parker wrote about this particular example.

“Maybe ten years ago, most Americans—and even most people in the education field—had never heard the term “school-to-prison pipeline.” It turns out that the first people who started calling out the school-to-prison pipeline, and who gave it a name, were black and brown parents and students in communities across the country.”

In 1998, more than 20 years ago now, organizers with Citizens for Quality Education in Holmes County noticed that a growing number of black children were out in the streets during school time. They started asking them, “Why aren’t you in school?” The kids told them they had been suspended for talking back to a teacher or other minor things. There was one case in which black kids on a school bus were throwing peanuts at each other, and one of the peanuts hit the back of the white school-bus driver, who then drove the bus directly to the police station. Five black boys were arrested for assault, and although the charges were eventually dropped, they had to drop out of school—for throwing peanuts around on a bus.

So the people who really pointed it out first, who got it into the public discourse, and who really drove the movement to build understanding and end zero-tolerance were the people who had been most impacted by the systemic abuses. They were the first to talk about the “school-to-jail” track, as they first called the school-to-prison pipeline. After they gave it a name and drew attention to it, researchers started to study the effects of zero tolerance and talk about the racial disproportionality, and the legal community started to address the violations of civil rights associated with the school-to-prison pipeline. Largely because of this movement, we’ve seen improvements in recent years. Suspension rates have declined in a lot of cities and districts, which is a great thing.

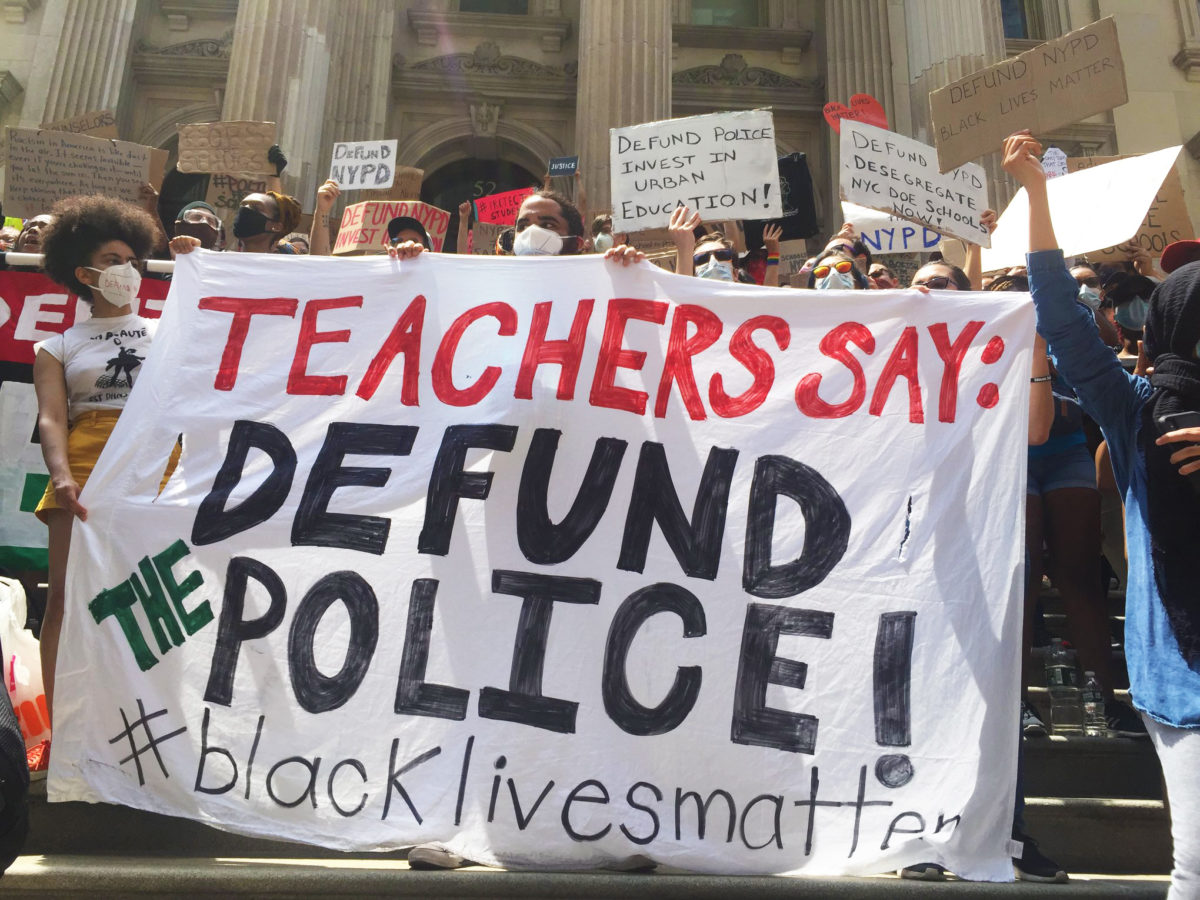

But a new feature of the problem has emerged that, once again, was first called out by the students and parents who were most directly affected: it’s the widespread presence of police in schools. During the 1990s, when schools were moving to adopt zero-tolerance policies that targeted minor misbehaviors and that produced dramatic increases in suspension rates, we also began to see a significant increase in the presence of armed police and security officers in schools.

Again, this police presence is not occurring, for the most part, in our affluent suburbs; it’s being seen in our inner-city and low-income schools. Which is ironic because when a tragedy happens, like what happened at the high school in Parkland, that results in calls for more police officers in schools, the additional police end up in schools located in low-income communities of color, which is not where mass shootings are happening.

Having police officers in schools is a huge issue. Once again, a lot of people don’t know just how many police there are in our schools today, or what it costs to have officers in schools, which is money that could be invested in more teachers and social services. There are 1.6 million children in public schools in the United States with at least one law-enforcement officer and no counselors, and the numbers are similar for students in schools with police officers but no nurses.

I was in Chicago, for example, and people don’t realize that there have been police substations located inside of high schools for many years. There are also metal detectors, and these armed police officers are sometimes arresting and booking children right in school in front of their peers and teachers.

In Los Angeles, police officers used to stand outside of the schools and ticket students for coming in late. I’m not saying that I think students should be late to school, but sometimes the buses aren’t running on time or older students have to be at home a little while longer to take care of a younger sibling—things happen and students arrive late to school for reasons that may be entirely outside of their control. Instead of welcoming them in, these students were being ticketed. Many of them can’t afford to pay the $100 tickets, so the tickets pile up, of course, then they end up in violation of court orders to pay the fines, and then the police come in and arrest them for failure to pay the fine, and they end up in the juvenile justice system. This is another way the school-to-prison pipeline works.

As we discussed, a lot of people don’t understand that these issues and processes are widespread in our education system. The school-to-prison pipeline is not just pushing students out of school, onto the street, and into the criminal justice system, but it also includes the large numbers of police officers in schools who are criminalizing, and sometimes abusing, our young people. Now the call, in the national educational-justice movement, is not just to end zero-tolerance, but also to end the regular presence of police in schools, and then use those funds to invest in counselors, nurses, teachers, and restorative-justice programs that can become alternatives to harsh discipline and pushout.

“A lot of people don’t understand that these issues and processes are widespread in our education system. The school-to-prison pipeline is not just pushing students out of school, onto the street, and into the criminal justice system, but it also includes the large numbers of police officers in schools who are criminalizing, and sometimes abusing, our young people. Now the call, in the national educational-justice movement, is not just to end zero-tolerance, but also to end the regular presence of police in schools, and then use those funds to invest in counselors, nurses, teachers, and restorative-justice programs that can become alternatives to harsh discipline and pushout.”

We should keep in mind that the rise of zero-tolerance and the presence of armed police in our schools started in the 1980s, and it became much more severe in the 1990s and into the early 2000s because it was part of the “three strikes” policies being implemented in the larger criminal-justice system—policies that were based on a profoundly distorted stereotype of black boys and men, particularly the black “superpredator,” a term popularized by the criminologist John DiIulio in a widely read Weekly Standard article. [EDITORIAL NOTE: Dilulio later admitted that his superpredator theory was wrong.]

Prejudice and stereotypes underpin the school-to-prison pipeline. It’s the stereotypes of young black men, and young brown men, that portray them as criminals, as violent, as dangers to our society, such as the widespread depictions we see in the media and in film. These prejudices and stereotypes translate into real-world problems. The larger proportion of our teaching force is white and female, for example, even in our communities of color. And very young boys of color, by the time they’re in third or fourth grade, are often seen as threatening by white teachers. The stereotype of the threatening black boy, even in grades two and three, is there, while young black boys, as early as preschool, who are rambunctious or who won’t sit still in a chair are seen as troublemakers. Yet the same behaviors by young white boys in suburban communities are just seen as harmlessly rambunctious or normal—they are not seen as troublemakers who need to be disciplined and controlled from a very early age.

We are actually seeing a high proportion of suspensions in preschool now—if you can believe that—and newer reports are showing that the school-to-prison pipeline actually starts in preschool, with children in kindergarten and pre-kindergarten being suspended from school for normal childhood behavior.

The first essay in our book is by Zakiya Sankara-Jabar (@ZakiyaChinyere), and she starts off by telling the story of her African American son, Amir, who was suspended and eventually expelled from a series of preschools, and how she came to understand, by talking with other black parents and looking into the research, that this wasn’t just her child’s experience, but it was a common experience for black boys everywhere. She became a racial-justice organizer and helped found a group in Dayton, Ohio, called Racial Justice NOW! (@RacialJsticeNow). In her essay, she talks about how she and other parents started to organize and eventually won a moratorium on suspensions for children in pre-kindergarten through third grade in Dayton Public Schools.

Q: You’ve touched on this point already, but in Lift Us Up, Don’t Push Us Out! you write that “successful movements are led by people who are most affected by injustice,” and you and your collaborator, David Goodman, chose to let local leaders, organizers, and activists tell their own stories in the book. Why is it so important that we listen directly to those who are doing the work of educational justice in communities? And why do we need to intentionally support and fund local organizations, groups, and movements being led by those who have been most harmed by injustice?

I think it’s essential that we listen directly to the people who are the most affected by injustice—that is, our students and families in low-income communities and communities of color. They are the people who are most directly affected by injustice, and we need to listen, as I’ve been saying, to their stories and their experiences, and we need to respond to them.

One of the reasons we need to listen, of course, is that their voices are often not heard. We see this play out in policy-making circles that are often very elite-dominated, perhaps by well-meaning people, but these circles are not intimately connected to the stories and experiences of people experiencing injustice. It’s their narratives that ground the work, I believe, in a strong sense of urgency, in strong moral passion, that compels us to do something about injustice today, not 30 or 40 years down the road.

“It’s essential that we listen directly to the people who are the most affected by injustice—that is, our students and families in low-income communities and communities of color. They are the people who are most directly affected by injustice. We need to listen to their stories and their experiences, and we need to respond to them.”

I also think that it’s important for the people who are most affected to be participating as leaders in the struggle for educational justice. When societies and communities have faced profound inequalities—let’s take Jim Crow segregation in the South—it’s those who have suffered through injustice who have been able to create movements that change that system, as they did in the Civil Rights Movement. These people have the strongest voices for demanding change, they have the strongest experiential understanding of the need for change, and when they get into motion—when they come to school-committee meetings or state legislative hearings, or when they rally in front of police departments or city hall—their presence and their articulation of the problem and their passion and their knowledge really moves people, and moving people is what produces change.

Because part of your question is about the need to intentionally support local organizations, groups, and movements that are being led by black and brown students, parents, and their allies, I think it’s very important to start at the local level. Movements that really create change start locally and build up from the ground. We certainly need national movements and coalitions, but I think it’s better to think about national movements as alliances that support and spread strong local organizing on the ground.

The fact of the matter is that probably 80% of our education policy is developed, and certainly implemented, at the local level or state level. This is where the levers of control can really be moved, and it’s also where the people who are most directly impacted can most easily, at least initially, get involved in organizing and justice work. This is where parents and students are living their lives. A lot of research has shown that it’s at this ground level that you can really get people involved in collective action.

But you can’t stay limited to local-level action. What you want to do is something called nationalizing local struggles. I got that term from Jitu Brown (@brothajitu), who writes about it in Lift Us Up, Don’t Push Us Out! Jitu is a community organizer in Chicago and the director of the Journey for Justice Alliance (@J4J_USA), a national alliance of local community-organizing groups. He was the leader of a hunger strike to stop the closing of Dyett High School in Chicago—the last remaining public neighborhood high school in the South Side, a historic African American community. The city and the mayor were going to close that school, and the organizers tried everything to stop the closure. They even developed a plan to transform the school into a school of green technology and global leadership, and they had it vetted by national education experts who determined it was a great proposal for the school.

The mayor refused. African American parents went on a hunger strike, and here we see the direct leadership of those most affected in the community. They also nationalized that struggle. They spread it all over the country. They used social media. They worked with the Journey for Justice Alliance. And their work brought all kinds of attention to Chicago. The hashtag #FightforDyett trended number one on Twitter for several days. The president of the American Federation of Teachers, Randi Weingarten, came to Chicago to support that strike. That helped break the media blockade—or whiteout, if you will—against the strike, which forced the media to cover it.

All this pressure ratcheted up and, eventually, the mayor capitulated. Dyett High School was saved and reopened as a school for the arts. I think this is an example of a campaign that was led locally, but where national alliances and movements supported it and helped win that victory. And it’s these victories that inspire people to organize against school closings or privatization that may be detrimental to their community in other parts of the country.

The same dynamic applies to the movement against the school-to-prison pipeline. When black parents in a group called CADRE (@CADREparents) in Los Angeles were the first to win a major change in district policy way back in 2006, which started moving the district away from zero-tolerance, that victory was nationalized. It was spread across the country. It inspired people in New York, Chicago, and Denver to take up similar campaigns, in part because they were able to get national support to help organize parents and students locally. In Denver a couple of years later, for example, local organizers in Padres & Jóvenes Unidos (@PJUnidos) won changes in the district’s code of conduct that moved away from zero-tolerance and toward restorative alternatives. That victory was then also nationalized.

I think this is the kind of dynamic we need to have. We need to be thinking about how we can support local organizations, strengthen them, and then spread their victories and their strategies across the country. Once again, this message is a central part of the purpose of Lift Us Up, Don’t Push Us Out! The book is about lifting up these local struggles, bringing them to light, and giving people a chance to hear them and understand how parents and young people made change happen in their community so that they will be inspired to create change where they live and work.

Another fundamental issue, one that is still not very well understood even within the more progressive social-justice foundation world, is how to appropriately fund and support local organizing. We absolutely need to invest directly in local organizing—in the parents and young people and teachers and their allies who are on the ground in communities. But it’s not all going to get done by local groups working on their own; we also need to build larger coalitions that are working to address more complex systemic issues at the state level or nationally.

Nevertheless, these local forms of organizing are not getting the kind of investment they need. Larger foundations typically only give very small amounts of money to organizing on the ground, and the real money that’s invested in organizing tends to go to larger regional or national alliances. I think about this problem in terms of social capital. Financial capital refers to money, of course, and human capital is about education, skills, training, that sort of thing. Social capital is about relationships and the social networks and infrastructure needed to create change. The social and professional relationships among parents, students, teachers, and their allies—these are the relationships that create the foundation for social change. Just like financial capital and human capital, we have to invest far more in the building of social capital. But it doesn’t happen overnight. Not only do we need more money going into supporting local organizing, but we need longer-term investment strategies so that foundations are not just putting a little here and there or funding something for only one year.

The kind of systemic change we need in public education requires a long-term organizing effort. Now, that’s not to say that we don’t urgently need change tomorrow—we do. We need to win victories and significant policy and practice changes as soon as we can. But we also need an investment that is sustained over five, ten, or fifteen years in local organizing work across the country. In the movement to end the school-to-prison pipeline, we’re trying to demonstrate that local organizing can make significant changes—that it has already made significant changes—and that the value of that work should be recognized by larger educational nonprofits and the foundation world. There’s an enormous amount of money that goes into those educational nonprofits, but it’s more focused on technical changes or curriculum changes, which certainly have value. But those technical changes are not necessarily shifting the fundamental realities on the ground, which are shaped by the profound racial inequities we’ve been talking about.

Q: You’ve just discussed the need for educators to form alliances with youth, family, and community organizers. Yet in many communities, educators and organizers have an adversarial relationship: school leaders may feel they are being unfairly judged or attacked, for example, while students and families may distrust representatives of a system that has repeatedly broken promises or failed them in the past. What advice do you have for school leaders and community organizers who want to initiate a dialogue that can begin to rebuild relationships and trust? Where can they start?

I think dialogue is a great place to start. But I also think that a number of things need to happen at the same time. First of all, I absolutely believe that we will eventually need to get to a point where educators are working with families and students and community groups to create the kind of change we want to see. As important as it is for communities to push for change from the outside, we need educators to be part of changing the system from the inside. We’re not really going to transform our educational system unless educators are part of that process.

Education is a human endeavor, so we have to change the hearts and minds of educators, and that often means educators have to get involved in the organizing process themselves. In the book, we have an essay by Sally Lee and E.M. Eisen-Markowitz, who are teacher activists in New York. They’re part of a group called Teachers Unite (@Teachers_Unite), and their vision is for teachers to organize other teachers at the school site into partnerships with parents and students to overcome zero-tolerance discipline and implement restorative-justice programs. They want to create authentically restorative and humane environments in schools.

Part of what we need is dialogue. It’s having teachers and parents and students talk about their personal experiences with one another. Most of the time, teachers don’t really know what’s going on in the lives of their students and families, and therefore they don’t understand the impact it has on them in school. Some of the things I’ve discussed today are examples. At the same time, parents don’t often have a chance to learn about teachers—to really understand why someone became a teacher, what they are trying to do in the classroom, how they are trying to make a difference in the lives of children and young people.

I think relationship-building at the level of personal one-on-one dialogue and connection is foundational—that’s where you start to build the social capital I’ve been talking about. I also believe that it’s going to have to be a struggle over policy, as well. If young people and parents in Denver, for example, are demanding that the school district take zero-tolerance out of its code of conduct, the Denver Classroom Teachers Association (@DenverTeachers) has to be willing to support it, not resist it. When teachers unions have resisted the demands of communities of color, it’s contributed to the creation of the historic divisions we now have pitting teachers unions against communities of color. We need organizers and activists inside of the schools and teachers unions to transform the way those institutions have operated.

And we’re seeing that happening. It happened in Chicago when the leaders of the reform movement became the leadership of the Chicago Teachers Union (@CTULocal1), and the union went on strike—not just for higher wages, but to bring arts and other programs for students back into Chicago’s schools. They took the position that teachers’ working conditions, the students’ learning conditions, and the families’ living conditions all mattered. By bridging those three things, they had overwhelming support from parents in the community when they went on strike. Again, in the book, we have an essay by Brandon Johnson (@BrandonCCD1) telling the story of that strike in Chicago. More recently, we saw a similar alliance in Los Angeles, where the Los Angeles teachers union went on a strike, and their agenda included something called “bargaining for the common good.” Their demands included not just higher pay for teachers—which is important—but also smaller class sizes, protections for immigrant children, and other policies that support students and families. So I think you need the personal stories, the one-on-one relationships, and the building of a larger social fabric that includes educator organizers leading within their own institutions in alliance with young people, families, and communities.

Q: You’ve studied numerous schools and education-organizing groups across the United States, and you’ve spoken with hundreds of people who are achieving remarkable results despite facing challenging odds. In the schools and communities that are making the most progress addressing structural racism and other inequities in the education system, what commonalities have you observed? What seems to work?

I think we’ve already talked about a few things. In general, though, where I’ve seen it work is in places where the foundation—the young people, parents, teachers, and community organizations—have been able to tell their stories to one another, organize themselves for action, and connect it to broader organizing campaign led by people who are determined and persistent. It doesn’t take a huge number of people to do this. It was surprising to me at first to see what a relatively small but determined and persistent group of parents and young people could accomplish. Persistence and determination and pushing it through, that’s one key thing.

Another key thing is funding—getting support from donors and foundations—so that these local groups at least have some resources behind what they’re doing. These could be local sources, not just national ones. In many cases, local organizers also need support from national movements and alliances, as I’ve discussed. We are now seeing this dynamic really emerging, and I think it’s critical. New coalitions such as the Journey for Justice Alliance, Dignity in Schools Campaign (@DignityinSchool), or the Alliance for Educational Justice (@4EdJustice) are some of the groups that we feature in the book. These national movement-building alliances can help the relatively small local groups build and expand their power. Places like Dayton, Ohio, which I mentioned before, where Zakiya Sankara-Jabar started Racial Justice NOW!, these are tough places to organize. If you have a determined group of local parents who have the support of a national movement, it can really help create some real change.

To achieve real transformation in public education, you also need to be able to take the next step to form deeper collaborations and partnerships. The reality is that changing policy is important, but then what? So the district can no longer suspend a child from prekindergarten to third grade—which is very, very important because schools have no business suspending children between pre-K and third grade, or even beyond that—but then the question is: What’s the alternative? Schools and teachers need an alternative, and they need to work with young people and families to determine what those alternatives should be. The alternatives might include social-emotional supports, positive behavioral supports, restorative justice, and practices like that. Then educators, students, and parents have to start organizing to make sure the policies are implemented and schools get the resources they need to support these alternative programs.

We can’t force a teacher to create a restorative and humane climate in their classroom. We can’t only have a policy that says you must have restorative justice in your classroom—we can’t just demand that outcome and walk away. If it’s only a demand, then it’s never going to really take hold. Teachers can resist the policy, treat it like just another policy that will pass in time like all the other ones before it. We need strong alliances in schools, unions, and communities that are changing hearts and minds and making sure the necessary resources are there—that’s what makes a difference.

Another thing we haven’t talked about so far is that the struggle for educational justice is not just a concern for students, parents, and teachers—it’s really a concern for our whole society. Other stakeholders, such as other unions, for example, have to get involved and become a force for change. In Massachusetts, the Massachusetts Education Justice Alliance (@massedjustice), which is part of a coalition of unions, organizations, and other groups that are pushing, at the state level, for more funding for public education, mass transportation, and other things. So building a coalition that works across movements and issues—what we sometimes call justice reinvestment—is also important. This approach might take money or resources from the policing and criminal justice system, for example, and reinvest them in public education, social services, public transportation, and other things that will ultimately help to solve downstream problems that contribute to the school-to-prison pipeline.

The struggle for educational justice and against racial inequities in our educational system is part of a larger struggle to address systemic inequities in society—the failures of our public education system are all connected to the more profound inequities in our society. If children are growing up in poverty, if they’re homeless, if their parents are in jail, if they’re suffering from environmental racism, those problems can’t be solved in schools alone. It takes a broader societal movement in which the struggle for racial and educational justice must be at the center.

Q: One last question. In your view, how has the rise of mass protests against police killings affected the educational justice movement?

First of all, people have to realize that these protests did not come out of nowhere. Years of organizing by groups in the educational justice movement and other movements laid the groundwork for the recent upsurge in protest. In particular, the police-free-schools movement has been building for many years, often led by young people involved in the kind of youth-organizing groups discussed in Lift Us Up, Don’t Push Us Out!, and coordinated by the Alliance for Educational Justice and other networks. This movement won victories to defund school policing in Minneapolis, Denver, Oakland, Portland, and other cities. In fact, almost all of the cities that achieved recent victories were cities in which young people had been organizing for police-free schools for years.

More broadly, since the educational justice movement is fundamentally a racial-justice movement that has increasingly taken an intersectional approach, the movement appreciates and understands the interconnections between the various forms of racial oppression that black people and people of color face. The movement is clear that we cannot simply go back to public education as it has been traditionally defined. Our public education system has been profoundly shaped by white supremacy, and we need more radical transformations to create an antiracist and liberatory education for black children and children of color. Despite the ravages of COVID-19, this agenda makes the current period an exciting opportunity for the educational justice movement and its allies.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Copyright

Copyright © by Organizing Engagement and Mark Warren. All rights reserved. This interview may not be reproduced without the express written permission of the publisher. Brief quotations are allowed under Section 107 of the Copyright Act.