Milton Bennett

Milton Bennett is the director and founder of the Intercultural Development Research Institute, and the creator of the Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity, a framework that is used internationally to guide the design and assessment of training programs in intercultural communication and competence. Bennett is an adjunct professor of intercultural studies at the University of Milano Bicocca in Italy, and he was formerly a tenured professor at Portland State University, where he created the institution’s graduate program in intercultural communication. He is the author of Basic Concepts of Intercultural Communication: Paradigms, Principles, and Practices, co-editor and contributor to The Handbook of Intercultural Training, and co-author, with Edward Stewart, of the revised edition of American Cultural Patterns: A Cross-Cultural Perspective. Bennett is also a reviewer for the International Journal of Intercultural Relations and Journal of Intercultural Education, and the author of many articles on intercultural research and practice.

Interview by Stephen Abbott

Q: I want to get to the Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity, but perhaps we could start with how you are using the ideas of “culture” and “intercultural” in the context of equity and diversity. I also think it would be helpful if you could describe the distinction between generalizations and stereotypes.

Sure. Since the 1960s, concerns about equity and diversity have mostly been associated with the encouragement and enforcement of civil rights—in other words, they’ve been political and legal issues. More recently, a lot of attention has also been given to prejudice-reduction and its extensions, such as implicit bias or microaggressions. I’ve been working with a less well-known approach to equity and diversity that also began in the 60s: intercultural communication.

In this context, intercultural communication is concerned with how we can understand and be respectful of differences in worldview, by which I mean the different ways we perceive and experience the world. People tend to think of this idea in terms of national cultures like French or Japanese, but it is equally applicable to cultural groups that are defined by ethnicity—which may or may not be associated with so-called “racial” differences—and gender, social status, age, ability, sexual orientation, or other group criteria.

“Intercultural communication is concerned with how we can understand and be respectful of differences in worldview, by which I mean the different ways we perceive and experience the world.”

Over the years in my work with schools, companies, and communities, I’ve found it’s helpful to think of different approaches to equity and diversity as different “levels of analysis,” each of which can be useful in particular ways. The levels are institutional, group, and individual.

An institutional-level analysis focuses on how organizations and societies enable some groups to exercise power while other groups may be systematically disempowered. This kind of analysis allows us to see that dominant ethnic or gender groups, such as European American males, are more likely to make institutional rules than are members of non-dominant groups—for instance, African American women. Even if the rules are not intentionally biased, they tend to favor the group that makes them. I find that members of dominant groups are reasonably open to this argument because it doesn’t target them as intentionally racist or sexist. Of course, traditional civil-rights remedies address these kinds of institutional issues, whether they are intentional or not.

An individual-level analysis focuses on the behavior and characteristics of people, including whether they are personally prejudiced, biased, racist, sexist, et cetera. There is a kind of optimistic assumption underlying approaches to equity and diversity at the individual level—that if people could just overcome their prejudices, or -isms of any type, they would relate more respectfully with members of historically denigrated groups. So individual-level approaches emphasize training and other interventions aimed at making people aware of their prejudices and encouraging them to treat others more humanely. Yet it is difficult to conduct programs at this level without making some people feel attacked. While defensiveness is an inevitable part of dealing with this issue, the cost—in terms of resistance to future programs and pushback—may be quite high.

Intercultural communication is located at a group-level analysis. This level focuses on the fact that all of us have been socialized into some group, which means that we have learned how to use language and other behaviors to coordinate action with the people around us—other members of our culture. Usually, we are not aware of our own culture—it just seems “natural”—and we may falsely assume that others share our view of the world. But even if we are culturally self-aware, we still have a natural tendency towards ethnocentrism and distrust of other worldviews.

So an intercultural approach to diversity tries to improve awareness of differences between one’s own culture and other cultures, and it teaches communication strategies that allow us to relate across cultural boundaries in more appropriate and respectful ways. I’ve found that people are usually more open to seeing negative stereotypes as the result of ethnocentrism rather than racism, which can provide a constructive context for less-threatening dialogue and training on the topics of bias and prejudice.

“An intercultural approach to diversity tries to improve awareness of differences between one’s own culture and other cultures, and it teaches communication strategies that allow us to relate across cultural boundaries in more appropriate and respectful ways. I’ve found that people are usually more open to seeing negative stereotypes as the result of ethnocentrism rather than racism, which can provide a constructive context for less-threatening dialogue and training on the topics of bias and prejudice.”

In response to your question about generalizations and stereotypes, an important skill in using intercultural communication is being able to generalize about groups without stereotyping individuals in those groups. In a nutshell, a belief or statement about a group becomes a stereotype when it is applied to any particular individual.

For instance, it is a true generalization that European Americans are, on average, less emotionally expressive than Latino Americans. This is a useful starting point for attempting to understand certain misunderstandings between the two groups. But if you meet a particular European American and say, “You must be uncomfortable expressing emotion,” then you would be stereotyping her as representative of the whole group, when if fact she might be someone who’s completely comfortable expressing her emotions.

Another way you can get stereotypes is by generalizing from too small a sample. This kind of stereotyping happens a lot internationally when people are traveling and they make judgments about, let’s say, French culture based on their interaction with a few French waiters. But domestically, it also occurs when our major contact with other cultural groups is either through the media or restricted to just a few people at school or at work. In those cases, the few people we see or interact with can easily be taken as representative of their group, when of course they are not. Also, for the purpose of improving intercultural relations, I should mention that positive stereotypes, such as “all Asians are good at math,” are no better than negative stereotypes, such as “all men are bad at relationships.”

Q: Let’s talk about the Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity. We’ll link readers to our introduction to the DMIS, so you don’t need to explain the model in detail, but could you describe the basic structure and progression of the model, including the concepts of ethnocentrism and ethnorelativism? And perhaps a few examples of how the model is commonly used?

I’m particularly happy to do so because the DMIS is still standing after its initial publication more than 30 years ago. I’ve made some tweaks to the theory, and I’ve of course updated the applications over the years, but the basic structure is the same. I think the model has been so resilient because it’s based on the fundamental process of human perception—that is, the ability to make discriminations.

It might sound strange to use the word “discrimination” positively in an equity and inclusion context, but that is what human perception is all about—the ability to differentiate figure from ground, to think or feel that this is a difference that makes a difference. Humans have the ability to discriminate instinctively about some things, but for the most part we pay attention to the differences emphasized by our families, cultures, personal interests, and education.

For instance, Italians generally learn how to discriminate many more forms of pasta than do non-Italian Americans. Or if you are a music lover, you have likely learned how to discriminate the sound of different instruments and the style of different rhythms and tonal configurations in ways that are imperceptible to casual listeners. That same idea applies to every kind of expert knowledge: discriminating one vintage of wine from another, the taste of one herb from another, or the effectiveness of one kind of motor oil over another. In each case, the ability to make complex discriminations is associated with your ability to experience something in a rich way that people without that perceptual ability either cannot experience at all or can only experience in a simple way

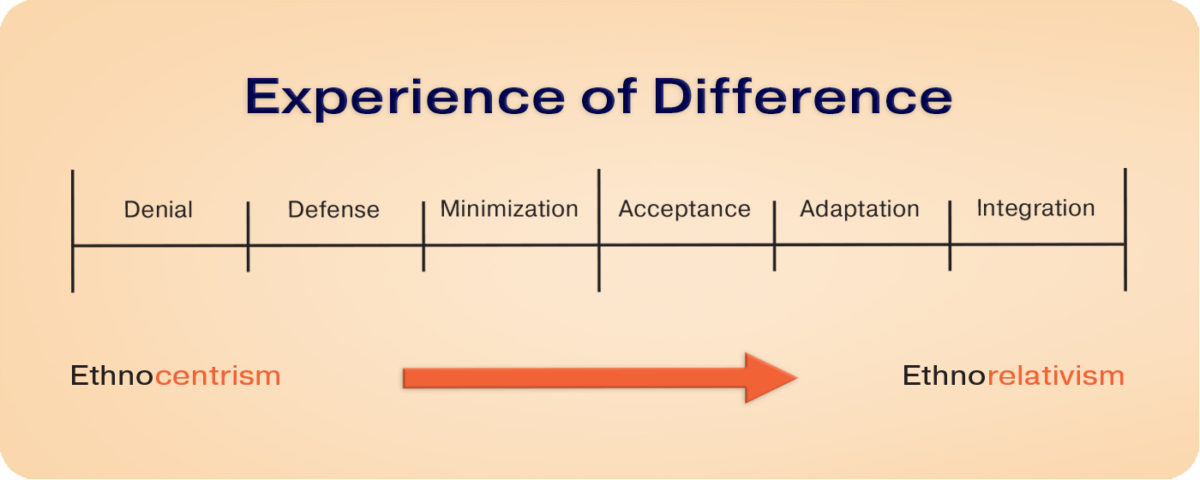

The DMIS is built on the observation that our perception of cultural “otherness” is also a skill that has to be learned. All of us are born into the default condition of ethnocentrism, where we see our own group as natural and complex and other groups as unnatural and simple. At the beginning of the continuum of development—the stage I call Denial—people do not discern cultural otherness at all; they may have a vague sense that something is different, but it’s not something that is worthy of their conscious notice.

When interacting with people at the Denial stage, members of other groups may feel as if they are invisible—at least in terms of their distinctive cultural attributes, but possibly even as human beings. People who are socially and culturally isolated, whether it’s through circumstance or choice, may not be motivated to move beyond Denial. Consequently, they may seem to be willfully ignorant of equality or inclusion issues that seem obvious to people with more experience and a greater understanding of cultural differences. People at the Denial stage genuinely just don’t get it.

Movement along the continuum occurs when we need to interact with members of other cultural groups in more sophisticated ways. First, Denial gives way to Defense, where people start to see and discriminate cultural otherness, but only in fairly simplistic and stereotypical ways. At this point, people recognize obvious issues associated with otherness such as immigration and segregation, but they tend to approach the issues in polarized “us and them” ways. Usually, it is “us” better and “them” worse—the well-worn path of populism and nationalism.

But sometimes that’s reversed and people experience others as better—for instance, people from non-dominant groups who have internalized racist or sexist beliefs about themselves or expatriates who have “gone native.” In addition to describing the obvious cases of oppressed people aiding their oppressors, this form of Defense, which I call Reversal, may masquerade as a more sensitive position than it is. For example, dominant-culture members who take on the causes of non-dominant groups while fiercely criticizing their own ethnicity may not be more interculturally sensitive; they may just have changed sides.

Denial and Defense are clearly not very effective communication strategies, so when there is a need for more coordination among groups, people move to Minimization. At Minimization, we emphasize how much the other is really like us. Dominant-group members start saying things like “I’m colorblind” or “deep down we’re all human.” While members of other groups may be offended by this disregard for their cultural differences, for people at Minimization the recognition of difference often seems like a regression to Defense, so they trivialize cultural differences as merely variations in things like music, food, or language. While people at this stage may be rather proud of their tolerance and interest in different customs, their underlying ethnocentrism precludes a more substantial appreciation of significant cultural differences.

“If ethnocentrism is thinking that one’s own culture is the center of reality—that it’s just the way life is—then ethnorelativism is seeing one’s own culture as just one way among many to organize human societies and social interactions. In ethnorelativism, you may prefer your own culture, but you also recognize there are other successful cultures that are different from your own.”

The minimum condition for respectful intercultural communication is Acceptance, which is the first stage of ethnorelativism. I use the term “ethnorelativism” to describe the opposite of ethnocentrism: if ethnocentrism is thinking that one’s own culture is the center of reality—that it’s just the way life is—then ethnorelativism is seeing one’s own culture as just one way among many to organize human societies and social interactions. In ethnorelativism, you may prefer your own culture, and even think it’s the best way to be in the world, but you also recognize there are other successful cultures that are different from your own.

So what “acceptance” means in this context is something like “I accept that other equally complex worldviews exist.” It doesn’t mean agreement with other cultural values nor does it imply that all cultural positions are equally good in every context. Rather, Acceptance is a kind of “critical relativism,” wherein we accept the viability of cultural alternatives but still choose our own commitment to certain values over others.

The practical application of

Acceptance is Adaptation, where we

attempt to understand others through empathy—or perspective-taking—and to

expand our repertoire of authentic behavior to include other cultural forms.

The important point here is that empathy has to be two-way; it is not just me

trying to understand you, but vice versa. The final position, Integration, refers to the habitual use of expanded cultural understanding

and behavior, such as when bicultural people easily shift between different

cultural modes of interaction.

I’ll also mention that the DMIS is generally used for three primary applications. One application is the diagnosis of individuals or collections of individuals for the purpose of targeting interventions, such as coaching or training. So, for instance, an individual whose predominant stage of development is Minimization could begin work on cultural self-awareness and perceptual strategies for recognizing relevant cultural differences. It would be too soon to do that work with people at Defense or Denial because they haven’t humanized otherness sufficiently to avoid stereotyping. Or if a person showed more Acceptance, the work would focus more on developing the skills of empathy and behavioral flexibility.

A second application of the DMIS is for program-effectiveness evaluation. By using fairly simple pre- and post-testing, it’s possible to show that a particular program was more or less effective in causing changes in intercultural sensitivity. The third application is program design. By sequencing material and activities appropriately, participants can be supported and challenged in ways that are both motivational and non-threatening. For example, DMIS-guided programs are often used to build the capacity of teachers, social workers, medical personnel, and others who work with multicultural communities and who need to create a climate of respect for diversity. Internationally, study abroad and exchange programs use the DMIS a lot to guide pre-departure, on-site, and re-entry intercultural learning. And corporations also use the DMIS to build and assess intercultural competence in their global operations.

Q: You mentioned this previously, but I think the distinction is important enough that we should talk about it a little more. The DMIS can help people address problems such as prejudice and discrimination, of course, but it doesn’t frame diversity or anti-racism work in terms of civil rights or political power, for example, or even in terms of individual or social psychology. Can you explain how the cultural, group-level framing of the DMIS is different from other approaches, and how developmental approaches are distinct from what you call “transformational” approaches?

Going back to the levels of analysis I mentioned earlier, the Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity allows us to look at relationships in terms of cultural worldview. For instance, the way people of European-American ethnicity value personal independence differs from the comparatively greater value given to group interdependence by African Americans. This cultural difference has profound implications for all kinds of behavior, including motivation for learning. If schools encourage and reward personal achievement a lot more than they reward group efforts, for example, they may be systematically more effective in motivating students of one ethnicity over another.

To be clear, there may also be racism and prejudice going on in schools, but it’s useful to be able to separate the kind of bias that comes from ethnocentrism from the kind that comes from one group trying to dominate another for some reason, which is what civil-rights work targets. Even if that civil-rights work is successful in changing policies in a school or workplace to make those organizations more equitable, it doesn’t get at cultural differences in worldview. Not only does this mean that certain issues such as learning-style differences may not be addressed adequately, but it misses entirely the goal of making diversity an educational or organizational asset.

Even in those areas traditionally approached with civil-rights advocacy or prejudice reduction, the cultural framing of the DMIS offers an alternative or complementary approach. When you treat prejudice as a personal attitude or as institutionalized privilege, it leads people to attempt to “transform” individuals or institutions to make them less prejudicial. While the transformative approach may sometimes be effective, success often comes with a price. People subjected to anti-prejudice efforts, but who are not transformed, may become even more adamant in their prejudice, which is now strengthened by hostility toward what they may perceive as inappropriate enforcement of “political correctness.” We are certainly seeing examples of this dynamic playing out in our current political discourse in the United States.

“When you treat prejudice as a personal attitude or as institutionalized privilege, it leads people to attempt to “transform” individuals or institutions to make them less prejudicial. While the transformative approach may sometimes be effective, success often comes with a price. People subjected to anti-prejudice efforts, but who are not transformed, may become even more adamant in their prejudice, which is now strengthened by hostility toward what they may perceive as inappropriate enforcement of ‘political correctness.’”

By treating prejudice as part of a stage of

development, the DMIS helps people to address prejudice as a developmental

issue rather than as a need for personal transformation. Developmental efforts do

not attempt to change people’s personal characteristics; instead, they provide

strategies for perceiving differences in more complex and less ethnocentric

ways. Not everyone will respond to developmental strategies, but the failure of

developmental approaches may not have as high a cost as the failure of

transformative approaches.

Actually, I’ve observed another problem with transformation strategies in addition to the potential blowback. It seems to me that a lot of anti-prejudice work is based on the premise that if people were not prejudiced, they would naturally default to relating to others in more respectful and constructive ways. I think that’s a questionable assumption at best. My observation is that our default condition is not to respect cultural differences, but to ignore them. In other words, Denial is the default condition.

People at Denial can, in a way, accurately claim that they are not prejudiced because they really don’t think about other groups at all. Similarly, people at Minimization are still ethnocentric and blind to important issues such as privilege, but they can rightly say that they are not prejudiced in the way they might once have been when they were in Defense. Essentially, the goal of a developmental approach is not so much to stop something like prejudice from happening but to develop something new—an improved cultural understanding and sensitivity. The more people know how to have respectful relations with others, then the less inclined they are to use simple prejudicial stereotypes.

Q: I think that one of the most useful concepts you’ve articulated is Retreat, which occurs when people are confronted with cultural difference and their reaction is to become defensive or lash out, particularly if they feel criticized or judged. I see this behavior play out all the time—not only in my own life and work, but also in our national political discourse. Can you explain the concept? And perhaps a few strategies facilitators can use to avoid triggering retreat responses when doing equity work?

Yes, I agree that this is a really relevant issue

just now. In short, Retreat refers to

people moving from a higher ethnocentric stage of development to an earlier

stage. The most common form of Retreat is to move from Minimization to Defense,

and it usually happens when people feel that their culture is being judged,

threatened, or attacked.

You could say we are now in a perfect storm of Defense, where people are becoming more and more polarized about more and more issues. Using my DMIS terms, there are three things happening simultaneously that are causing this perfect storm.

One is the normal process of people moving out of Denial into Defense, but that movement is happening at an accelerated pace due to increased contact with immigrants, refugees, and global foreigners in our social relations, and due to political rhetoric and media coverage that stokes fear of otherness.

Additionally, as you mention, people are retreating from Minimization to Defense. Minimization looks good on the surface—be tolerant of others, try to treat everyone the same—but it’s a really unstable condition. It doesn’t take much for a demagogue to shake a lot of people out of their tolerance and back to seeing others in terms of simplistic, less-than-human stereotypes. Even Acceptance, which is usually safe from Retreat, has been hijacked by bigots who are claiming that racism and sexism are characteristics of an alternative worldview that should be respected. Unfortunately, this gathering storm is likely to become even more violent unless some of the contributing factors can be weakened.

“The best we can hope for in the current paradigm is a kind of balance of terror, where abuses of power, such as implicit racist or sexist discrimination, are challenged with the power of negative sanctions such as public shaming. This scenario is not a very good foundation for creating respectful relations. I believe we need to be moving towards the new paradigm of constructivism, where the goal of communication is mutual empathy—or the joint responsibility for us to understand each other—and where ethicality is not based on easily hijacked universal principles, but on a collective commitment to equitable ways of being in the world.”

There is not much we can do about immigration and refugee movement, for example, given that it is being driven by political, economic, and environmental crises and upheavals. It might help if there was less sensational media coverage, of course, since research shows that communities where immigrants actually live are less fearful than communities that just infer a threat from the media. On the other hand, media can be useful in exposing the inhumane tactics being used by some governments to counteract mobility.

For diversity workers, the good news is that there’s

a lot we can do about retreat from Minimization. For too long we have been

exhorting people in Defense to recognize the terrible cost of their prejudice,

and, when successful, leaving them in the unstable condition of Minimization. An

increasing number of diversity workers have been arguing that we need to move

beyond tolerance, which means that anti-racism programs and newer implicit-bias

work needs to spend less time on what not

to do and more time on what to do.

Facilitators also have to move beyond Minimization in their own development to help

participants become more accepting of alternative worldviews and more adaptive

in multicultural situations.

Regarding the hijacking of Acceptance, we also need to recognize the limitations of cultural relativism. Certainly, a relativist paradigm is more appropriate in multicultural contexts than the absolutist Social Darwinism that it seeks to replace, even if bigots claim its protection for their racism. But more importantly, the paradigm fails to provide us with alternatives to power as the basis of all intergroup relations. The best we can hope for in the current paradigm is a kind of balance of terror, where abuses of power, such as implicit racist or sexist discrimination, are challenged with the power of negative sanctions such as public shaming. This scenario is not a very good foundation for creating respectful relations. I believe we need to be moving towards the new paradigm of constructivism, where the goal of communication is mutual empathy—or the joint responsibility for us to understand each other—and where ethicality is not based on easily hijacked universal principles, but on a collective commitment to equitable ways of being in the world.

Q: A few years ago, you worked on a large training project with the Clark County school system in Nevada. One of the major goals of the project was to help the district build school cultures that are more respectful of diversity and difference. How did that project work? And, in your view, what are some of the major obstacles to changing school climates and professional cultures?

The Clark County project was an exercise in doing exactly what I just described—moving into a constructivist paradigm and honing the skills of facilitators to guide school teachers and administrators in that direction. It was a particularly important project, since Clark County already has the cultural demographics that are likely to characterize the entire United States by about 2050. So success in this district could well mean that a developmental-constructivist approach could be increasingly effective elsewhere.

The program was called “Building a Climate of Respect for Diversity.” The approach was explicitly based on the idea that we should be talking about what to do more than what not to do. So the focus was on developing intercultural competence, such as recognizing relevant cultural differences among the multicultural students and staff; finding communication strategies that were respectful of those differences, while still effective in coordinating educational activities; and building capacity in teachers and staff to engage each other and students in mutual adaptation. Of course, an important part of building capacity is dealing with the common forms of Defense, such as prejudice and stereotyping. But the developmental goal was not just to limit Defense behavior; instead, it was to move through Minimization into the ethnorelative positions of Acceptance and Adaptation. In DMIS terms, the end of this process is Integration, where constructivist intercultural competence is “just the way we do things around here.”

A really important part of this approach is that it

begins with the most knowledgeable and committed people available; you might

say, the people who “need it least.” In Clark County, this group consisted of

around 30 people drawn by invitation from the ranks of teachers,

administrators, and staff. The group completed 80 contact hours of training

over a period of two years, which involved about ten days of seminars, virtual

meetings, and substantial amounts of reading and group-project work. In effect,

the group that began as the most qualified people in the district went through

a process that made them really extraordinary representatives and practitioners

of an intercultural-competence approach to equity and diversity. The next stage

of the process is for the group to work in every school with other teachers,

administrators, and staff through training, coaching, and consulting to build a

climate of respect for diversity that is based on improved intercultural

sensitivity.

“The major obstacle to using an intercultural-competence approach to diversity issues in schools in the same one that exists in societies at large—which is the idea that prejudice and bigotry are personal flaws that can be overcome, and that learning what not to do will be adequate for intergroup relations. In my experience, this mistaken idea keeps diversity work on the extracurricular sidelines. If diversity is approached as learning what to do in multicultural relations, it can be positioned as a more central educational strategy in schools, organizations, and communities.”

I would say that the key element for conducting a program such as the one in Clark County is buy-in and support from top administrators. Diversity work in general, and this approach, in particular, does not work very well in an organizational context as a grassroots effort; that’s probably because the topic is bound to be threatening to some people in a school district or workplace, and they will then complain that the program is wrong-headed or unnecessary. Unless administrators are prepared to defend the program, it will probably not survive.

Another issue in schools is that the primary focus of teacher training is usually new classroom activities or teaching strategies. An intercultural-competence approach depends on teachers being willing to devote time to self-development and on their being able to identify and facilitate interactions between cultural differences in multicultural classrooms. Teachers who are not already committed to achieving this competence are sometimes resistant to professional development that focuses on them rather than on new classroom activities.

Overall, I’d say that the major obstacle to using an intercultural-competence approach to diversity issues in schools in the same one that exists in societies at large—which is the idea that prejudice and bigotry are personal flaws that can be overcome, and that learning what not to do will be adequate for intergroup relations. In my experience, this mistaken idea keeps diversity work on the extracurricular sidelines. If diversity is approached as learning what to do in multicultural relations, it can be positioned as a more central educational strategy in schools, organizations, and communities.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Copyright

Copyright © by Organizing Engagement and Milton Bennett. All rights reserved. This interview may not be reproduced without the express written permission of the publisher. Brief quotations are allowed under Section 107 of the Copyright Act.