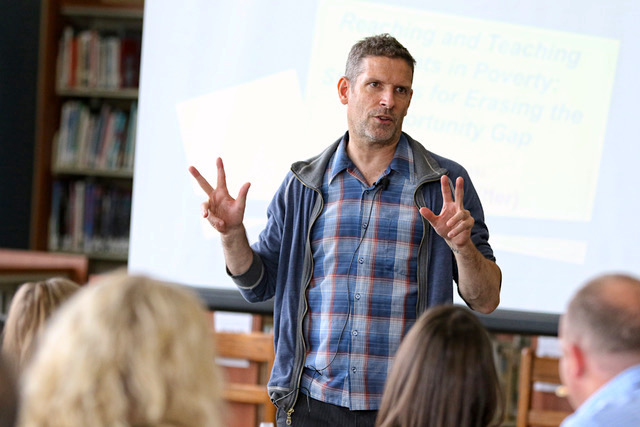

Paul Gorski is the founder of the Equity Literacy Institute and EdChange. For more than 20 years, Gorski has helped educators in 48 states and a dozen countries strengthen their equity programs and practices in districts, schools, and classrooms. He has published more than 70 articles and has written, co-written, or co-edited twelve books on a variety of subjects related to educational equity, including Reaching and Teaching Students in Poverty: Strategies for Erasing the Opportunity Gap and, with Seema Pothini, Case Studies on Diversity and Social Justice Education. Gorski is also the author of the Multicultural Pavilion, an online compendium of free resources for educators.

Interview by Stephen Abbott

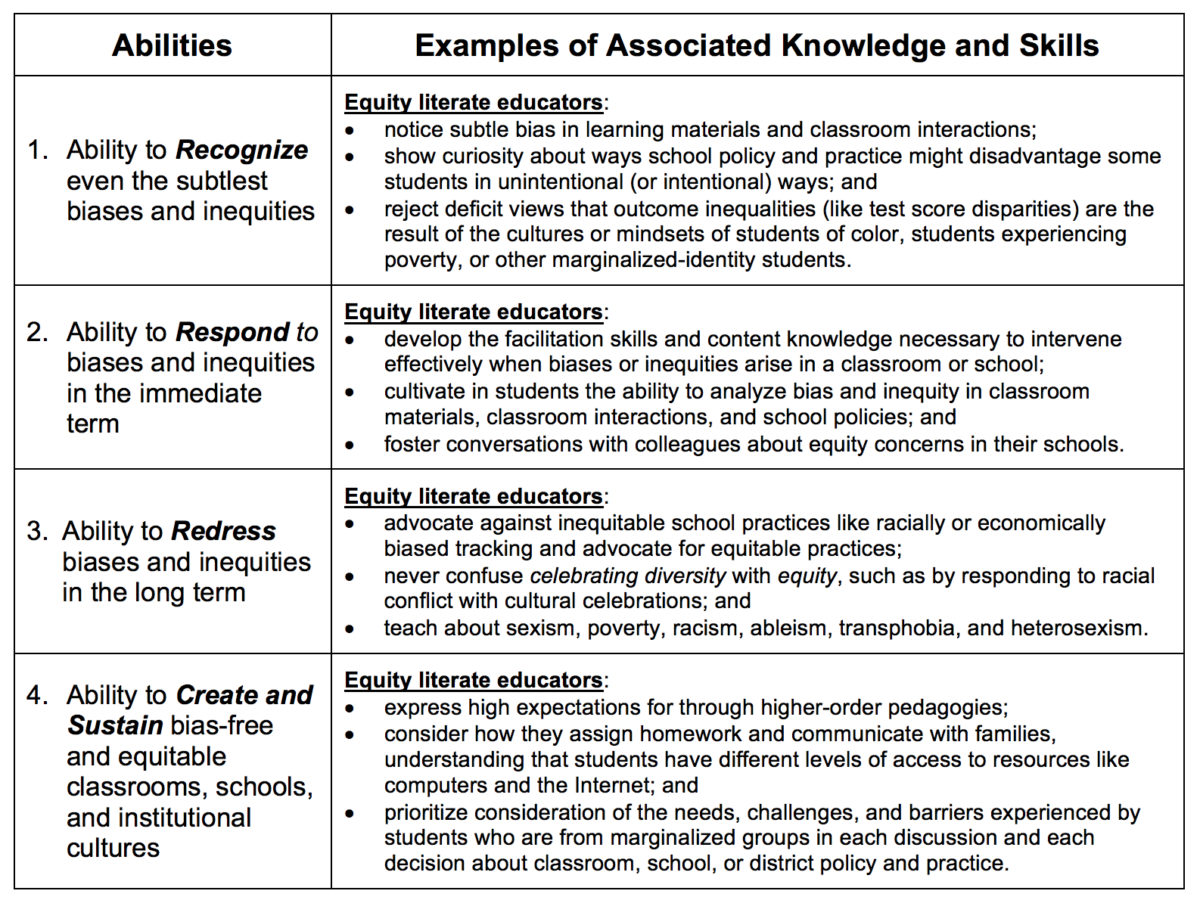

Q: You developed the Equity Literacy Framework to help people, in your words, become a threat to the existence of inequity. Why did you feel that it was necessary to create a new equity model? How is equity literacy different than, say, a concept such as “cultural competency”?

Our intention really was not to create a new model. Katy Swalwell—the co-architect of the equity literacy framework—and I were frustrated about how equity conversations always seem to be driven by simple strategies and shiny new initiatives. The reality is that a majority of the strategies and initiatives implemented in schools in the name of equity have no shot at creating more equity. What the education world was missing, we thought, was a depth of understanding: How do equity and inequity operate in classrooms and schools? Why do educational outcome disparities exist? What was also missing was the will to make the changes necessary to root inequities out of educational systems.

Instead of asking these sorts of questions, what we so often see are schools implementing grit initiatives or growth mindset initiatives and calling them “equity strategies”—like we want to help students of color be more resilient against racial inequities while we ignore the racial inequities. So the framework was created initially as a set of ideological tools, really, to help push educators to look more deeply at what was happening. A few other models—culturally relevant teaching, for example—have this deeper digging built into them. But as Gloria Ladson-Billings, the creator of that framework, has pointed out, schools often implement it without the deeper digging, without confronting racism or sexism or heterosexism, for example, and they instead focus on cultural celebrations or minor bits of curricular diversity.

We worked on developing an approach that does not allow for that sort of evasive implementation. How do we create a framework that puts—and keeps—equity at the center of the conversation? Instead of dancing around the issue, we ask: How is racial inequity operating in this school right now? How can we best understand the roots of this inequity? What is the most immediate way to eliminate this inequity? We want to gently but firmly force people to stay in that conversation.

We also recognized that not everybody has developed the understanding necessary to stay in that conversation. So equity literacy is a framework that provides a set of tools for strengthening and then implementing those understandings. It’s meant to provide guidance to schools that might be celebrating diversity, or focusing on cultural competence, but struggling to address inequities.

It’s interesting that you ask about cultural competence, by the way, because we often use that framework as a way to describe what’s unique about equity literacy. Cultural competence is important. Knowing something about the cultures of our students and families can help us interact with them more effectively and relate to them more deeply. But knowing a bit about African American culture—which is, in itself, a bit of a misnomer because there’s enormous diversity among African Americans—is not the same as being able to recognize subtle forms of racial inequity in school policies or to recognize the ways ableism creeps into classroom practices.

And we need to be careful not to confuse racism or heterosexism or ableism with cultural problems. I mean, they are problems that might be based in institutional cultures, but they’re not interpersonal cultural conflicts. Instead, they’re problems with how access and opportunity are distributed in society and in school, and they’re problems that result from differences in power and privilege. Equity literacy works on that level of awareness.

Read the Organizing Engagement introduction to Paul Gorski’s Equity Literary Framework →

Q: One of the foundations of equity literacy is a total rejection of deficit narratives, such as the view that communities of color need to be “fixed” or that students from low-income backgrounds are “at-risk” because they live in an imagined “culture of poverty.” Why are deficit narratives so insidious and harmful? And what can people do to actively name, challenge, and reframe these narratives in their schools and communities?

Deficit narratives are really a symptom of a mindset that most people are taught if they’re raised and socialized in the United States. That’s why they’re so insidious—they’re very normalized. Why does poverty exist? Deficit narratives tell us that it’s because people are lazy or because they don’t value education. If you believe the United States is a meritocracy, and that everybody has equal opportunities if they just apply themselves, and that what we achieve is a perfect reflection of our effort—that old “bootstraps” mentality—then it’s very easy to embrace a deficit interpretation of educational or economic disparities.

Part of the problem is that there’s a big and growing industry of educational concepts and initiatives that revolve to some extent around the idea that we can close educational gaps by adjusting the mindsets, values, grittiness, behaviors, or social and emotional intelligence of students. And in most cases, though it might not be said out loud, these initiatives are being specifically applied to students of color, students experiencing poverty, students who are learning English, and students with (dis)abilities. Grit, growth mindset, trauma-informed practices, mindfulness, social-emotional learning…what I find curious is that the people who developed these practices and initiatives never pitched them as equity strategies. Carol Dweck, who developed the concept of growth mindset, has explicitly said her framework is not an equity strategy. And yet it’s implemented in schools all over the country as an equity strategy.

“We challenge deficit narratives by making an intentional choice: equity efforts should never be about fixing anything about students who are marginalized in schools. They should always—always—be about fixing whatever is marginalizing students in schools.”

When I think about why that’s happening, it’s rooted in deficit ideology. All these practices are alluring because they avoid the harder work of equity—because they don’t require that we identify inequities, how they are operating in schools, and how we’re complicit in them. I want to clarify: I do think that—in the context of a robust systemic approach to equity—some of these practices can play an important role. I wish my own teachers had access to trauma-informed classroom practices, for example, because I grew up with a lot of trauma and generally felt like I was repeatedly punished for the impact of that trauma. But what none of these approaches help us do is identify and eliminate inequities that are deeply embedded in our educational systems. When we’re not eliminating inequities, we’re instead trying to help students adjust to inequity-laden institutions—we’re feeding that classic deficit ideology.

We challenge deficit ideologies by learning how to spot them in all their forms. Educational leaders have a big role to play here: they simply cannot allow deficit narratives and assumptions to live in their school or district cultures. On a more interpersonal level, when I hear somebody make a deficit-oriented statement, I like to ask a question that invites that person to look through a more structural lens. Somebody might say, “These low-income families just don’t value education. They never show up for anything.” In this case, I might ask, “I wonder if there are any other possible explanations for why those families are less likely than wealthier families to attend family-engagement events? Could there be an explanation other than they don’t care or they’re irresponsible?” In this way, I’m inviting somebody to try on a different lens.

Ultimately, we challenge deficit narratives by making an intentional choice: equity efforts should never be about fixing anything about students who are marginalized in schools. They should always—always—be about fixing whatever is marginalizing students in schools.

→ For an in-depth discussion of deficit ideology, see Gorski’s article “Unlearning Deficit Ideology and the Scornful Gaze: Thoughts on Authenticating the Class Discourse in Education“

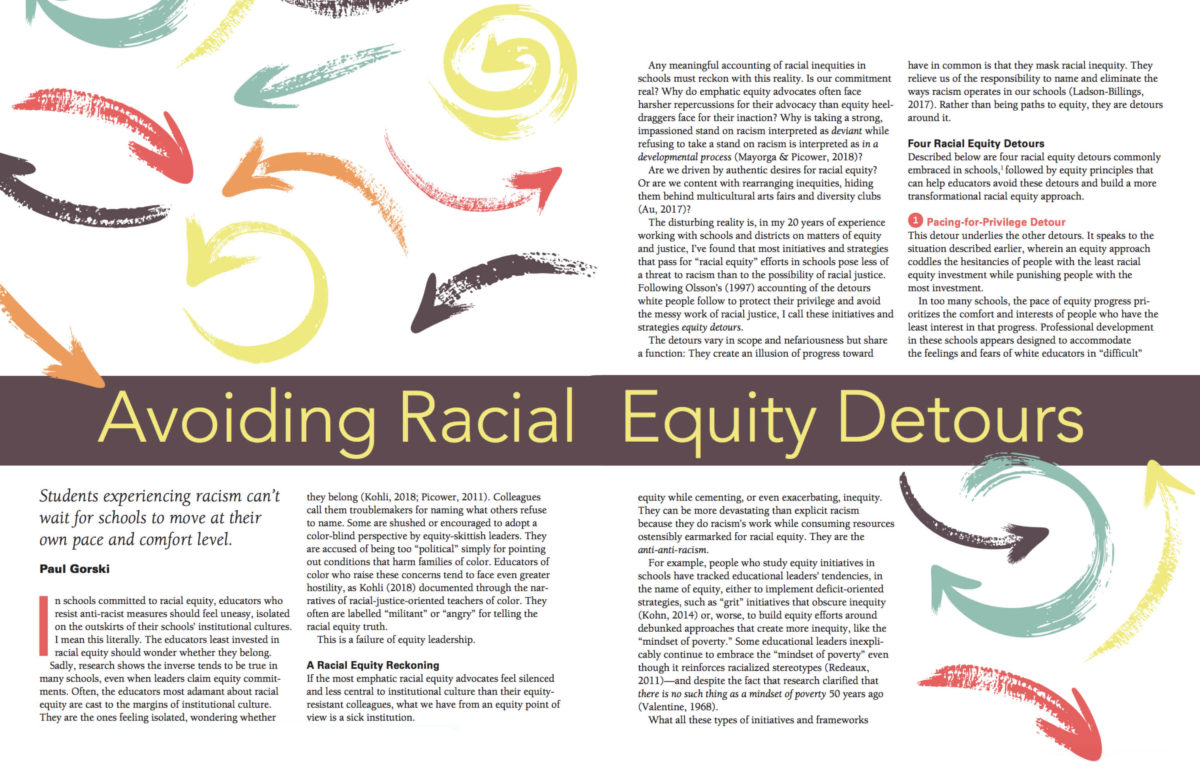

Q: In a recent article in Educational Leadership, you introduce the concept of “equity detours,” or well-intentioned initiatives that take a lot of time and resources but that fall far short of achieving genuine equity in practice. Can you provide a few examples of common detours? And how can school and community leaders avoid them?

The most common detour is probably the pacing for privilege detour. This happens when equity work is implemented at a pace that is comfortable for the people who are most resistant to conversations about equity rather than at a pace that demonstrates an urgency to create more equity. Another common detour is the celebrating diversity detour, which happens when we confuse surface-level diversity programming with meaningful equity initiatives that directly address inequities. And we already talked about the deficit detour—or trying to adjust the mindsets or behaviors of, say, students of color while ignoring the inequities bearing down on them.

There’s a basic principle we can follow to avoid the detours. I call it the direct-confrontation principle. Equity work is about identifying and eliminating inequities. I always come back to these questions: How is racism operating here? How are heterosexism and homophobia operating here? What is the quickest way to eliminate them? If we stay laser-focused on identifying and eliminating the challenges and barriers that create inequity, we can avoid the detours.

Q: You’re someone who gets called in when schools or districts are reeling from incidents of racism or prejudice—incidents that are increasingly going viral on social media and making national headlines. While these incidents can motivate communities to finally take steps to address inequity, calling up the equity consultant is often used as a quick-fix crisis-management strategy. What do you tell school leaders who find themselves in a crisis and want to take meaningful action? And more importantly, what should schools be doing to prepare for and avoid such incidents?

It’s interesting because, in some contexts, it seems like we’re just waiting for something awful to happen, then responding to it, rather than proactively addressing the school conditions that are doing damage to students right now. So most of my work is about helping schools proactively address those conditions. We need to see the existing inequities—the subtle day-to-day stuff—as a series of ongoing crises.

When I’m called in during terrible, event-driven crisis situations, I work with school leaders to understand why the crisis event happened and which aspects of their institutional culture might have contributed to it. Sometimes the impulse is to look at these big events as isolated events, but they’re never isolated. They’re always connected to a bigger set of conditions in schools and communities.

Again, most of the damage is not done through these crisis events, but rather through the grinding, day-to-day things that are being driven by that bigger set of conditions. So what I do is work with schools to recognize that those things are crises too—that the entire state of schools, where inequity exists, is a crisis we need to address right now.

I was working with one district where the leadership was trying to manage the fallout from a crisis event that involved white students at a high school taunting African American students with Confederate flags and the N-word and other racial slurs, which led to some physical altercations. My sense was that the leadership really wanted to respond effectively, and they knew they had to do some serious work. Their mistake, though, was that they immediately framed the incident as an isolated event. They tried to assure the community that they valued diversity and that the district didn’t condone racism. They were responding to the crisis of the event rather than the crisis of racial inequity.

The African American students, the targets of the incident, didn’t see it that way at all—that is, as an isolated crisis. They saw the racist taunting as just an escalation of what they were experiencing all the time at school. So the administration further lost the students’ confidence by not being honest or complete in its response. That, to me, is an example of the problems that can result from a lack of equity literacy.

“The leadership really wanted to respond effectively, and they knew they had to do some serious work. Their mistake, though, was that they immediately framed the incident as an isolated event. They tried to assure the community that they valued diversity and that the district didn’t condone racism. They were responding to the crisis of the event rather than the crisis of racial inequity.”

In my work with this particular district, I interviewed several of the students who were the targets of the taunting. Their view of things—and I agree with them—was that the district leaders were confusing the optics of equity with actual equity. They were choosing short-term image-management and further alienating their most alienated students. So my work with them was about how they could shift from that approach to one that was more about listening and responding to the students’ experiences and addressing the deeper, more insidious conditions that created the context that led to the big racist event. I worked with the leaders to ask deeper questions: What is it about the institutional culture here that made those white students feel like it was perfectly normal to behave in such a racist way? What is it about the institutional culture that made you, in essence, re-abuse those students by prioritizing the district’s short-term image over their experiences?

We worked on shifting their focus from short-term equity optics to sustained, long-term equity transformation, starting with the central issue: What do we need to do right now to root that racism out of our institutional culture?

Q: In your writing and workshops, you talk about the importance of will—that educators, and especially educational leaders, not only need equity knowledge and skills, but they also need the will to use their knowledge and skills to do the right thing, even if it results in opposition, criticism, or attacks. What does “will” look like when it comes to equity? Do you have an example of a school or district leader doing the right thing despite knowing that it would upset or anger some people?

When it comes to equity, having will means doing the right thing despite the blowback. It means being committed not just to an equity philosophy, but to equity action.

I want to be a bit careful here, though, because will needs to be supported from the top of the power structure. It’s hard to tell a teacher to do the right thing when doing the right thing might get the teacher punished or fired, for example. I also know that there are things I can say as a white man about equity and inequity that will be heard completely differently, and punished more harshly, if a woman or person of color says them. That makes me feel an elevated sense of urgency to tell the equity truth.

Here’s an example of a leader demonstrating will: I was working with a group of superintendents in Pennsylvania a few years ago, and I asked them for examples of when they had demonstrated equity will even though they knew they’d face blowback. One superintendent described how he had two high schools in his district—one on the wealthier side of town and one on the higher-poverty side of town. The parents in the wealthier school often raised big money to support school activities. In the other school, the parents worked just as hard and were just as invested, but they didn’t have the means to raise that kind of money. As a result, the students who had the most access and opportunity were getting additional access and opportunity.

“The superintendent decided—against the wishes of his district’s school board—to implement a new district policy: all the money raised by parent groups connected to any school would go into a central district pot, and then the money would be distributed based on need. This was a bold equity move, and super unpopular among powerful families in the district, but the superintendent did it because it was the right thing to do. That, to me, is true equity leadership.”

The superintendent decided—against the wishes of his district’s school board—to implement a new district policy: all the money raised by parent groups connected to any school would go into a central district pot, and then the money would be distributed based on need. You can imagine just how angry this policy made many of the parents at that wealthier school.

This was a bold equity move, and super unpopular among powerful families in the district, but the superintendent did it because it was the right thing to do. That, to me, is true equity leadership.

One problem is that when people are trained to be school administrators, their training usually doesn’t address how to manage blowback from those kinds of strong equity decisions. My organization does a lot of work with administrators to develop the knowledge and skills required to lead bold, equity-oriented organizational change. In the same way, teachers aren’t always prepared in their teacher-education programs to identify and eliminate inequities in their classrooms and schools. It’s a set of knowledge and skills people need to develop, and that set of knowledge and skills is what we call equity literacy.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Copyright

Copyright © by Organizing Engagement and Paul Gorski. All rights reserved. This interview may not be reproduced without the express written permission of the publisher. Brief quotations are allowed under Section 107 of the Copyright Act.