Raquel Jimenez

Raquel Jimenez is the executive director of equity for Oakland Unified School District, which educates 35,938 students in 83 schools. Jimenez has more than 25 years of combined teaching, nonprofit, and grassroots and school-based youth, family, and community organizing and engagement experience in Oakland. Jimenez joined the Oakland Unified School District leadership in 2007, and she works to advance racial justice, equity, and healing throughout the district by working across departments and with the community to build capacity for student, parent, and community partnerships both inside and outside of schools.

Interview by Stephen Abbott

EDITORIAL NOTE: During the latter half of the 2018–2019 school year, when this interview took place, many districts across the state of California, including Oakland Unified School District, were experiencing severe budgetary challenges due to declining student enrollments in district-run schools.

Q: It must be a particularly crazy time for you. While we’re having this conversation, Oakland Unified is facing $30 million in potential budget cuts and the school board is preparing to vote on possible school consolidations and staff layoffs. It also looks like the district’s teachers are preparing to strike, and students and families are organizing to oppose the looming cutbacks. It’s hard to imagine a context in which constructive community engagement is more urgently needed. What’s it like to be a district director of engagement and equity at a moment like this?

It’s beyond challenging to say the least. Yet I

also think this moment is an opportunity because it’s shining a light on the

knowledge gaps in our system when it comes to truly understanding what it takes

to do constructive and meaningful engagement. With everything that’s happening

right now, it’s forcing us as district leaders—and really everyone in our

system—to be more self-reflective and actively acknowledge that we need to do

engagement in a different way. So that’s the opportunity.

What’s challenging is coaching people up,

particularly across staff roles and decision-making power, and really getting

them to engage with asset-based thinking and language so they can understand

the difference between authentic engagement—with the goal of building trust,

relationships, and partnership—versus information sharing. In our situation

right now, many decisions need to be made quickly due to political and

financial pressures, so we don’t have optimal conditions to design and execute

opportunities for family partnership or community collaboration.

While this is our reality right now, some of our

leaders are still holding on to the notion that we can do both—that is, share

information quickly and speed through

a process to build trust, relationships, and two-way partnerships. Yet

when it comes to decisions about finance and school redesign, this approach is

just not possible. We need to decide if we’re willing to take the time to

engage for the purpose of partnership and shared ownership or if we can live

with just sharing information.

For example, when designing a community meeting

that’s about getting input on the criteria we’ll use to determine which schools

will be selected for our Blueprint for Quality Schools cohort—these are schools that

are going to be consolidated, expanded, or redesigned to achieve our goals for

increasing quality school options in every neighborhood—it’s critically

important that we clearly explain what decisions the community will be involved

in and what decisions will be made by district leadership.

My message to our leadership team is that we need to make decisions about power-sharing, and we need to determine precisely how we will and won’t be sharing power with our community, at different points in the timeline for a specific project. If we are not willing to share power on important decisions—or if we decide that we simply don’t have the time for authentic engagement—then we can’t call a committee a “stakeholder engagement committee,” for example. Maybe we can call it an “information-gathering committee” or something else that clearly articulates to the community that all we are doing is sharing information, and that we are not engaging in a shared decision-making process. Families and community members value transparency, and they will appreciate that the district is making the purpose of the meeting clear.

As a district director, another challenge for me

is making sure that I’m always true to the principles and values that have

guided me throughout my journey as a learner and leader in creating systemic,

transformative change—whether I’ve been a community organizer, a nonprofit

leader, or a district administrator. I need to make sure that I’m being

transparent when I share the information with the community, and I need to make

sure that information is accurate. But the challenge, of course, is that the

information I share with the community needs to be consistent with the district

leadership’s understanding of that information. Let’s take an important

committee decision, for example. In some cases, the messages being communicated

by our community organizers conflict with the messages that our district

leaders are communicating—but they’re both talking about the same issue and

decision. I’m often standing in the middle of those tensions, which is made

even more challenging because, in most cases, neither side is being 100%

accurate or clear.

Another related problem is that we often use a

lot of jargon and “eduspeak.” When the community can’t make sense of the

information the district provides, they create their own understanding and

analysis, which can then cause even more tension. So what’s difficult is

translating, in a way that makes sense to the community, what’s happening with

our budget, or our citywide plans to move the district toward financial

stability, so that we can have quality schools in each neighborhood. We lose

sight of what it is we should be communicating at all times: care. Making that plan accessible and

understandable to students, families, and community members is hard, it takes

time, and it’s just not easy to use a language of care, responsibility, and

commitment if we were never trained to reflect on and recognize deficit

thinking and framing or to practice asset-based thinking and language.

Ideally, we would be structuring in time for

equity and engagement learning with our senior leaders so that we’re better

prepared to lead with asset-based thinking, language, and practice during

difficult times. With this knowledge gap, and with the decision-making process

moving so quickly, it’s often not possible to do authentic engagement well. My

hope is that we can learn from this challenge. Right now, we’re developing a

plan for more meaningful equity-focused family engagement next year that will

allow us to authentically engage the community on sensitive decisions and

develop a timeline that allows us to do it well.

Another knowledge gap I’ll point out is when district leaders loosely throw around terms such as “student engagement,” “family engagement,” or “community engagement” when they’re talking about any activity that touches students, families, or the community. Misapplying the language of engagement can set up expectations that the district then fails to deliver on. Engagement is a process, not a meeting, and it involves two-way learning between staff and community. Engagement is not a survey. A survey may be one tool used in an engagement process, but it is not in itself a form of engagement. So this is the kind of thing I mean when I say “knowledge gaps.”

Here’s another example. One component of our

citywide plan to achieve financial stability is the reorganization of the

central office, which is following a massive layoff. Right now, the

“community-engagement process,” as it’s been designed, is a series of meetings

over the next two months during which the district will present the key drivers

of the central-office reorganization. This is a necessary process, of course, but

does the community care enough about the process to attend a meeting? And have

we decided what the purpose is for this “engagement”? Or how we’re going to

share power and use the feedback we collected? Just because you have a meeting,

and a few community members come by, you can’t just check the box and say, “We

did community engagement on the central-office reorganization.” Right? That’s

another example of a knowledge gap.

For me, any student, family, or community engagement process should be focused on building trust, strengthening relationships, and acknowledging histories of inequity, which begins with our own personal values and beliefs about our community. Do we truly believe all children can achieve at high levels? Do we truly believe every parent wants the best for their children? Do we truly believe all parents can support their child’s learning? Do we truly believe that partnerships with our students, families, and communities, particularly with those furthest from opportunity, are critical to solving our district’s greatest challenges? Engagement is a two-way set of activities that gets the community to a shared solution that deals with the root cause of an issue.

“Engagement is a process: it starts at the very beginning with community members looking at an issue, analyzing data, and engaging in a conversation to develop a shared understanding of how we got to where we are. Engaging in public learning with our community also creates and repairs trust. This public-learning process needs to help students, families, educators, and leaders develop a shared understanding of our context, what we can do to improve, and what conditions need to be created to get us to where we want to be. That would my simplified description of a meaningful engagement process.”

Let’s consider an issue such as designing

quality standards for a community school, for example.

In the process of convening young people, parents, and community members, there has to be an acknowledgment that quality is lacking, an understanding of why we have low-quality schools, and a shared definition of quality. In our community, there also needs to be an acknowledgment that our schools are where they are because of a history of white supremacy and institutionalized racism in this country, and we need to acknowledge and talk about how that history has played out in Oakland and in our school system.

The first step needs to be that acknowledgment. We then need to acknowledge all of the things that were tried in the past that didn’t work—all of the mistakes that were made in the community or in the schools. To rebuild trust and faith with the community, they need to know that we’re learning from past mistakes. They also need to know that we care about repairing harm, and that we want to work with them to create a shared definition of quality schools for our students.

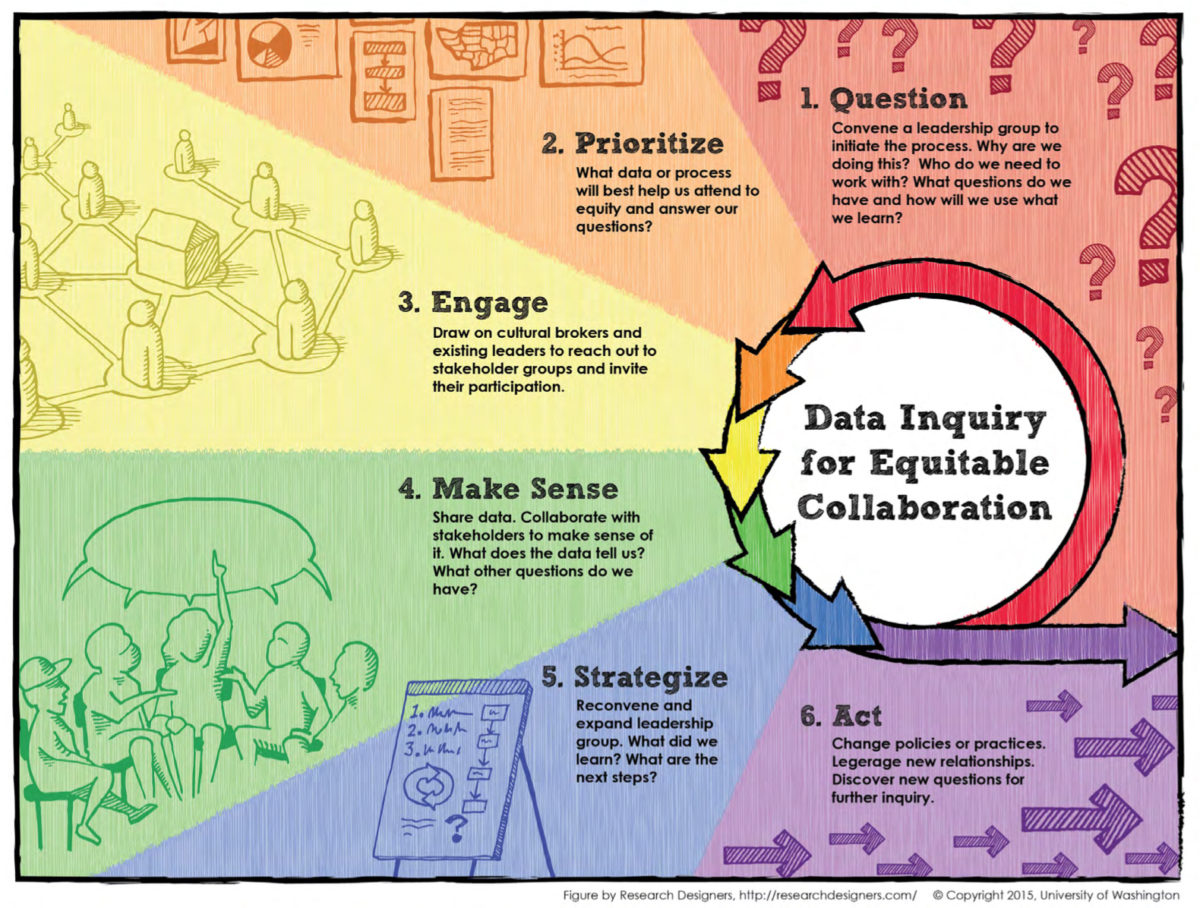

One of my other principles of engagement is always engage students, families, and

community members closest to the issue from the very beginning and in the

analysis of the problem. Educators might call this process a “cycle of

inquiry.” In our engagement work, we often look at data. Do we understand how

African American, Latino, or Pacific Islander students are doing, for example?

Or how our English learners or students with special needs are doing? What

about the cross-section of Latino students who are English learners and have

individualized education programs? How are they doing?

Once you’ve looked at the data, you can then

engage the community in a learning process: Where we can go from here? What are

other schools doing to increase the achievement of our target populations? Can

we try what that those schools are doing here at our school? What do teachers

and administrators need to do? What do parents and students need to do?

That’s what I mean when I say that engagement is a process: it starts at the very beginning with community members looking at an issue, analyzing data, and engaging in a conversation to develop a shared understanding of how we got to where we are. Engaging in public learning with our community also creates and repairs trust. This public-learning process needs to help students, families, educators, and leaders develop a shared understanding of our context, what we can do to improve, and what conditions need to be created to get us to where we want to be. That would my simplified description of a meaningful engagement process.

For an example of a cycle of the inquiry that has been in community-engagement contexts, see the Organizing Engagement introduction to the Equitable Collaboration Framework, which describes a six-step Data Inquiry for Equitable Collaboration process designed to guide action-research projects in culturally diverse districts, schools, and communities.

Q: You have a somewhat atypical background for a district administrator. Not only are you a graduate of Oakland’s public schools, but your family has roots in the city dating back to 1950s. You have also held leadership roles in the school system as both a student and adult, and you worked for many years as a grassroots community organizer who was at times critical of the district. How has your background and personal investment in the community shaped your approach to student and family engagement?

I think my background is one of the assets I

bring to the school district. When I was interviewed, the district

administration had a mindset that fit well with my background and principles. The

administration wanted to create an office of student, family, and community

engagement that would systemically build community critical friendship and constructive criticism into the district’s

decision-making process, particularly around school improvement. It didn’t

happen by accident. The leadership at the time was influenced by a sustained

community campaign to build a structure that would engage youth, families, and

the community on a consistent basis—not just with one-off or emergency issues.

So that’s essentially what I do.

My approach is to build community trust and

leadership, while also showing people that we cannot get better without

students, families, and community members playing a leadership role in school

change. I’m still the same community organizer I’ve always been—it’s just that

I’m now working inside the district. What’s challenging in this role, however,

is the community seeing me as a district employee. For community members who

don’t know me and who aren’t familiar with my background, I often get the

immediate reaction, “Oh, she’s the district, so we can’t trust her.” But once

these community members see the work and the actions we take, the wall comes

down pretty quickly.

Another thing that’s somewhat unique about my background is that my specialization in graduate school was racial and ethnic studies in education. And that’s not just my professional specialty; it’s also my passion. I strongly believe that the only way we’re going to disrupt racism in our institutions and advance racial justice is by developing the capacity of students, families, community members, and educators to work together to improve education through a racial justice, equity, and healing lens.

I also bring my experience with community

organizing to the development of our staff teams, whether they’re in service

roles, teaching roles, or leadership roles. In our staff-development work,

we’re engaging in conversations about the root causes of educational inequity.

We’re talking about the internalized racism we all carry around, the harmful

effects of interpersonal microaggressions, and the institutional and structural

barriers that get in the way of the work.

At Oakland Unified, we’re now at a place where

our Office of Equity is part of the district’s academic division.

The office is working to inform teacher professional development and, in

collaboration with other departments, increase the social-emotional learning and

equity mindsets of everyone who works for the district. This June, we’ll be

hosting a standards and equity institute for teachers across the content areas

and in all grade levels. No matter what they’re learning or talking about

during their scheduled professional-development week, all of them will be

reflecting on bias, inequity, and the mindsets they bring to their classrooms

and interactions with families. This is just one example of how my background,

and ability to form partnerships, is helping to reshape district

approaches.

“One of the skills I think we need to refine, as educators, is being comfortable with being uncomfortable—because that’s the mindset that’s necessary for change to take place. It’s only when we invite in constructive criticism that we’ll hear about what’s not working in the system or how our work is being experienced by students and families.”

Another thing I’ll mention is that one of the

skills I think we need to refine, as educators, is being comfortable with being uncomfortable—because that’s the

mindset that’s necessary for change to take place. It’s only when we invite in

constructive criticism that we’ll hear about what’s not working in the system

or how our work is being experienced by students and families. Sometimes that

feedback is going to be uncomfortable because it feels like an attack on the

hard work we do every day. When someone in the community criticizes something

that’s happening at a school, many educators feel like it’s a direct criticism

of them—not a criticism of the system.

Our principals, teachers, and staff are

definitely hardworking, and I understand why criticism doesn’t feel good—it feels

like it’s targeting you and ignoring your hard work. But that’s not why we need

to invite criticism in, and it shouldn’t be a reason why we avoid it. We need

our community to shed light on the things that need to change, and we need to

engage in an honest dialogue that builds trust. More than anything, I feel like

that’s what engagement work is all about: building or rebuilding the trust that

has been broken. We need to demonstrate that we are aware of our mistakes, that

we’re learning from our mistakes, and that we’re committed to figuring it out

together.

In my view, experience and skill in anti-racist community

organizing and trust-building should be one of the standards that districts

apply when hiring engagement staff. What engagement teams do is help educators,

students, and families move through a cultural and relational process of

two-way learning, analysis, and decision-making—and that’s exactly what anti-racist

community organizers do. What I’ve tried to do is build trust within the

district, and in the community, using two-way approaches.

“There’s a difference between an organizer and an advocate. An organizer is someone who has built a community base and who serves those people. An organizer develops the leadership abilities of others—they are not the leaders themselves. An advocate is someone who speaks up and speaks out on behalf of others who don’t necessarily have a voice. However, the advocate may only be representing their own opinion, and not necessarily the voices of a representative group of people. People who are vocal at board meetings may only be speaking for themselves or their family, even if they claim to be representing others. As district leaders, we have to pay close attention to these distinctions because they’re absolutely critical.”

At the same time, we also need to be mindful of appropriate roles and definitions. I don’t know if this is an issue in other cities, but in Oakland it seemed like all kinds of people suddenly started identifying themselves as organizers or advocates. I’ve had to do a lot of work making distinctions about these roles and raising awareness among our district leadership teams.

There’s a difference between an organizer and an advocate, for example. An organizer is someone who has built a community base and who serves those people. An organizer develops the leadership abilities of others—they are not the leaders themselves. An advocate is someone who speaks up and speaks out on behalf of others who don’t necessarily have a voice. However, the advocate may only be representing their own opinion, and not necessarily the voices of a representative group of people. People who are vocal at board meetings may only be speaking for themselves or their family, even if they claim to be representing others.

As district leaders, we have to pay close

attention to these distinctions because they’re absolutely critical. Sometimes

different voices may be in conflict in communities, and some voices may be more

representative than others. For example, our students may decide they want to

organize around an issue that places them in conflict with other members of the

community, such as a particular parent group. When we say we want to welcome in

critical voices, we need to be aware of these nuances, such as who’s speaking

on their own behalf—not their cultural group—or who represents a narrow

interest group—not the majority of the community.

So the question becomes: Whose voice are we going to listen to? Are we listening to the community members who are going to be deeply impacted by the decision? Are we listening to the organizers who have been working in the community for years to build unity and collective voice? Or are we just listening to the people who are loud at board meetings or who have connections, influence, wealth, or racial privilege?

Q: I want to talk a little more about Oakland Unified’s commitment to sharing power and decision-making with the community. While many districts express a desire to engage their community, they often want to engage on their own terms. For example, they may attempt to control the process by determining the parameters and objectives in advance, by scheduling and facilitating all the meetings, or by excluding or marginalizing voices they disagree with. You’ve already talked about why you feel a power-sharing approach is so essential, and particularly in communities where there has been a history of tensions or distrust. But how did power-sharing become a priority for Oakland Unified?

Well, it’s not by accident that our approach is different. I mentioned this briefly, but there was a community-led campaign to develop standards and protocols for involving the community in decision-making, which is now part of our school-governance policy. In Oakland Unified, our governance policy sets standards for our school site councils and defines what shared decision-making looks like in practice. That was a huge win for the community.

Other district policies also come into play and give us the leverage we need to meaningfully engage our youth, families, and community. For example, we have a policy that established standards for family engagement, and we also have a rubric that provides guidance for staff members who are implementing family engagement in their schools. And we have a student-engagement policy that sets standards for our middle schools and high schools; it articulates how students should be meaningfully involved in decision-making. More recently, our school board passed a sanctuary policy that defines what it means to be a sanctuary school for Oakland Unified staff. We’ve developed protocols for protecting our immigrant students and families, and we’re now expanding that sanctuary definition to include what it means to provide safe and affirming spaces for black students and families, girls and young women of color, and LGBTQ students and families.

With these policies in place, I think our school board really set the bar for authentic engagement. The family-engagement and student-engagement policies include statements that frame the district’s engagement work in terms of racial justice and equity. That language is key because it gives us leverage to ask difficult questions with our principals and teachers: What does equity look like on this campus? How are you changing instruction and learning conditions for students furthest from opportunity?

When we can be direct, candid, and intentional about

issues of inequity and injustice, it sends a message to our community, and it

communicates that we actually care. There are many other things that we’re

doing, but I feel like those policies have given us the leverage we’ve needed

to do this work in ways that have not been allowed or supported in other

districts. If we need to, we can always refer back to the policy and say, “This

is not an optional approach, actually, this is our directive.” We’re able to

refer back to these policies and really hold staff accountable. For example,

we’ve integrated deadlines into our deliverable calendars for principals that

require them to log how many times they’ve engaged families in supporting

student learning at home, or how many capacity-building trainings they’ve

scheduled with our family-engagement and school-governance teams.

“The policies that let us actually operationalize authentic engagement would not have been possible before the community organized and demanded changes that eventually made their way into district policy. And now we’re at a place where—even in the midst of huge budget challenges—our superintendent is not only on-board but explicitly naming equity as one of our main drivers for change. She is set to open our standards and equity institute by naming the root cause of inequity—systemic oppression—and naming that we must be engaged in equity learning.”

But keep in mind that all of this came from the community.

The policies that let us actually operationalize authentic engagement would not

have been possible before the community organized and demanded changes that

eventually made their way into district policy. And now we’re at a place where—even

in the midst of huge budget challenges—our superintendent is not only on-board

but explicitly naming equity as one of our main drivers for change. She is set

to open our standards and equity institute by naming the root cause of inequity—systemic

oppression—and naming that we must be engaged in equity learning. And our chief

academic officer is saying, “We’re not going to be able to move the needle on

achievement if we’re not intentional about addressing our target populations, engaging

families, and if we’re not listening to students.”

Before our Student, Family, and Community Engagement Office was created in 2007,

Oakland Unified had actually experienced a lot of success in some of our small

schools where family engagement was the foundation of the design. Schools like Think College Now, Melrose Leadership Academy,

International Community School, Acorn

Woodland Elementary School, Encompass Academy, and Coliseum

College Prep Academy all resulted from very strong

grassroots campaigns that engaged parents and communities in the design of the

school. There was an intense, authentic process that looked a lot like what I

described earlier: engaging families in an analysis of the data and an ongoing

cycle of inquiry, learning, designing, and implementing. I think that having

these previous experiences and successful models in the district also helps—we

can point to these successes and say, “Now we need to scale up this kind of

work and build it into all of our systems.”

Q: One of the foundational engagement strategies you mentioned is building the knowledge, skills, and agency of students and families so they can increasingly assume leadership roles in the district’s engagement work. This kind of “capacity building” is a frequently stated objective in community-engagement work, but the term is often left undefined. Can you give us your definition? What does capacity building mean in practice? And what are you specifically doing to build community capacity in Oakland?

Part of the definition is in your question.

Capacity building is certainly about increasing knowledge and skills, but it’s

also about building confidence. I think confidence is key, and to build

confidence we use a very specific approach when working with students and

families that grounds them in their own identity and experiences. For young

people, it might mean educating them about their history and culture, for

example. Our student-leadership curriculum includes an ethnic-studies section

for a reason—it’s because our young people have experienced deculturalization in schools where their racial identities

have not been valued or affirmed. So you have to do some work to rebuild their

sense of cultural pride and confidence—to get them to see that they’re

beautiful and brilliant and talented, and that they have something to give.

That’s one part of building confidence.

“For many parents and family members, what you know is less important than what you show—they want you to show them that you care about their child. That’s another essential part of the work: building school communities and spaces that are nurturing, valuing, and affirming of culture and race. Once we’ve built confidence and affirming spaces, then you can start building the knowledge and skills required to be a representative leader.”

This approach applies to families, as well. For

many parents and family members, what you know is less important than what you

show—they want you to show them that you care about their child. That’s another

essential part of the work: building school communities and spaces that are

nurturing, valuing, and affirming of culture and race. Once we’ve built

confidence and affirming spaces, then you can start building the knowledge and

skills required to be a representative leader.

And that’s another component of our

student-leadership curriculum: teaching young people what it means to be a

representative leader. What does that look like in practice? How do you do

action research? Then once they have engaged their peers and constituents on

the issues that matter the most to them—they have listened to their ideas and

their proposed solutions—they have to come up with an action plan to implement

some of those solutions. It’s really about taking young people through the

whole process of how change happens in a school or community, which begins with

grounding them in who they are. To me, that’s how you start to build the

capacity of young people, families, and teachers.

Recently, I started developing a Latino-teacher

pipeline for our district. A lack of racial or cultural representation on a

teaching staff is actually one of the big causes of low achievement among

Latino and African American students. Research has shown that if students of

color have an experience with even one teacher of color during their elementary

years it can have a significant positive impact on academic achievement later

on, so we want to bring more teachers of color into our system.

As I’ve been working with these new teachers,

I’ve found that they also need cultural healing. They need to be grounded and

affirmed in who they are, and they need to talk about the microaggressions and

other biases they have and will continue to experience in schools. What I’ve

found is that building staff capacity also requires making space to talk about

race and culture and oppression—how we’ve internalized it and how we can heal

from it. Once that foundation has been established, we can then move on to

discussing the legacy we want to create as social-justice-minded educators of

color.

That’s what capacity-building means to me. Yes,

it’s about building the content knowledge of teachers or the skills required to

be a representative leader, but it needs to be grounded in an ongoing

commitment to nurturing cultural identity and pride, and to making space to

mourn and heal from past personal, collective, and historical traumas.

I’ll add one more thing: building community

capacity also means that we need to model restorative approaches to difficult

conversations. That’s another part of the work we do with our student, parent,

and community leaders—we build their confidence and skills to hold restorative

circles, engage in respectful conversations on difficult topics, and create

healing spaces where they can repair relationships and acknowledge feelings of

trauma, distress, hurt, and pain. Just making space to acknowledge all of that

is profoundly important. After we’ve named and talked about all the difficult

and uncomfortable issues, the next step is deciding how we are going to move

forward together to fix it.

Q: As you just described, your philosophy of engagement is grounded in social-justice theories and practices. But many school leaders do not see greater social, political, or economic justice as the desired goal or outcome of engagement work. What would you say to other administrators or teachers who may be reluctant to discuss issues such as systemic racism or classism? Why should districts take the lead in disrupting and dismantling bias, discrimination, and inequity in their schools and community?

If you want to improve student achievement, I

would say that you need to address the racial patterns in the data. You have

look at inequity in resources or staffing or outcomes in your school district—you

have to look at the root causes. A lot of research also suggests that you have

to engage in targeted approaches for your target populations so they can

develop a sense of belonging and an academic cultural identity.

To do all that, you need to build the capacity

of educators at all levels of the system to analyze data and determine root

causes. School leaders and educators need to get on the same page about the

root cause of a problem—for example, that today’s achievement problems have

historical roots in racism and the way education has been provided to African

Americans, Latinos, Asians, Pacific Islanders, Native Americans, and other

communities of color. We need to look at the history of deculturalization,

genocide, and slavery, and at attempts to “invisibilize” or color-blind race in

schools.

“When school communities don’t have honest discussions about dismantling systemic racism, or when they intentionally avoid the problems of bias, discrimination, or inequity, they are only going to continue to harm their students. This kind of avoidance prevents educators from engaging students in schools and classrooms, and it often results in those students disengaging from school altogether. If we are going to be serious about engaging all students or improving achievement, we also need to engage in self-examination.”

When school communities don’t have honest

discussions about dismantling systemic racism, or when they intentionally avoid

the problems of bias, discrimination, or inequity, they are only going to

continue to harm their students. This kind of avoidance prevents educators from

engaging students in schools and classrooms, and it often results in those

students disengaging from school altogether. If we are going to be serious

about engaging all students or improving achievement, we also need to engage in

self-examination. As leaders of schools and districts, we need to understand

how our students are experiencing education, whether those students are Latino-Indigenous

students, Polynesian students, African American students, LGBTQ students, Middle

Eastern students, or students with special needs. We have to pay attention to

their experiences and we have to understand them.

We also have to acknowledge the mistakes school

systems have made, and we need move forward in solidarity with our students,

families, and communities. I think we now have enough research showing that educators

not only have to teach to the standard, but they need to engage students in

standards-based instruction using asset-based practices that build empowering

narratives about our students and families, that counter deficit thinking, and

that integrate our students’ and families’ cultural and linguistic assets in

the learning process.

So, yes, let’s make sure to teach rigorous

academic standards to students in the classroom…and let’s also make sure that we affirm who they are so that they

feel safe, seen, and nurtured.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Copyright

Copyright © by Organizing Engagement and Raquel Jimenez. All rights reserved. This interview may not be reproduced without the express written permission of the publisher. Brief quotations are allowed under Section 107 of the Copyright Act.