As the executive director of the Participatory Budgeting Project, Shari Davis oversees the organization’s operations, technical-assistance programs, and advocacy work. Davis joined Participatory Budgeting Project after working for 15 years in local government. When she was the executive director of the Department of Youth Engagement and Employment for the City of Boston, she launched the first youth-led participatory budgeting process in the United States, Youth Lead the Change. Davis initially got involved in city government as a student leader in high school, serving as the citywide neighborhood safety coordinator on the Boston Mayor’s Youth Council. In 2019, she was honored with an Obama Foundation Fellowship for her work on participatory budgeting.

Interview by Stephen Abbott

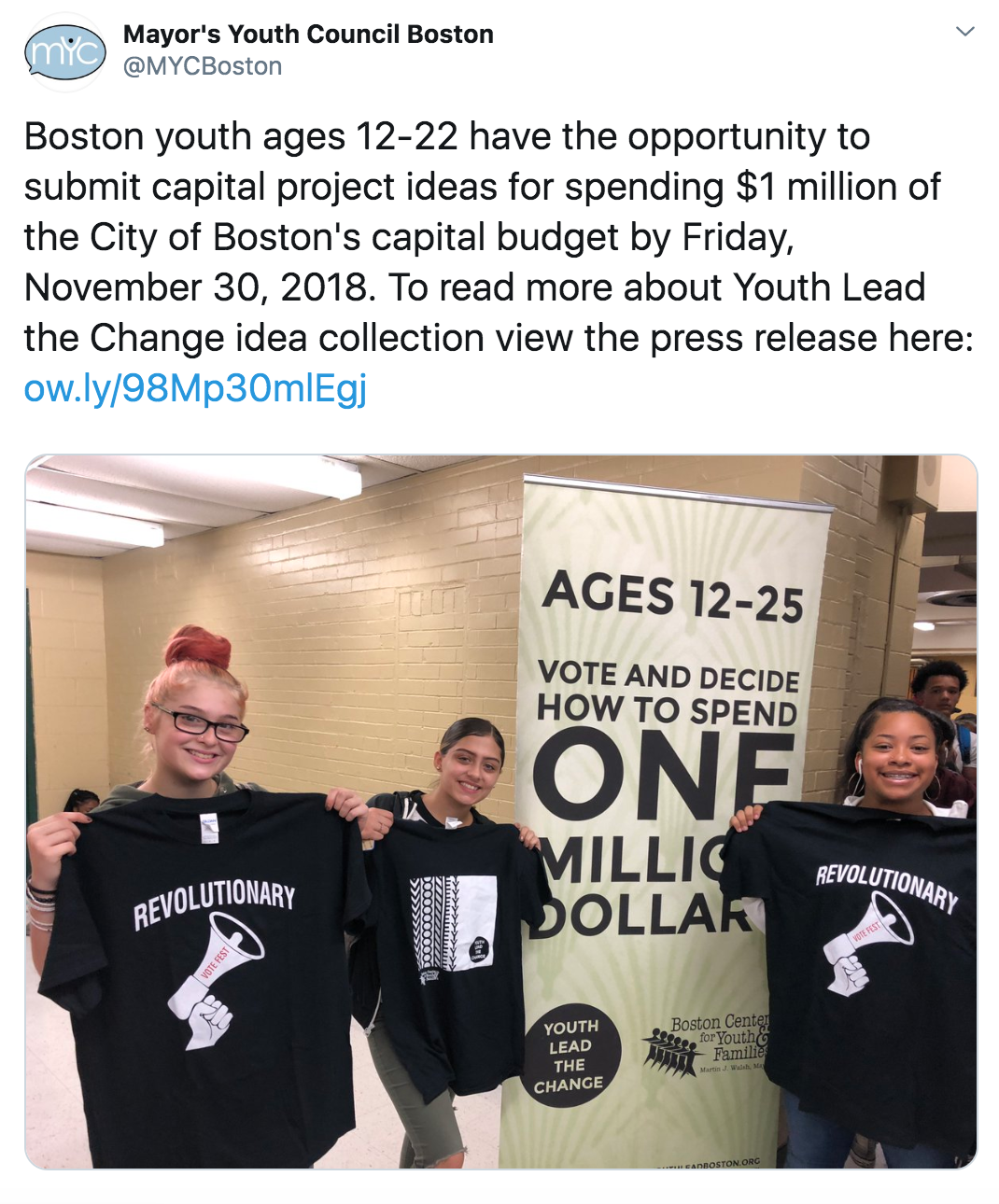

Q: Let’s start with the work you did in Boston. In 2014, you launched the first youth-led participatory budgeting process in the United States with $1 million in funding from the city budget—and the annual process is still going on today. Can you tell us how the project got started and how it worked? But more importantly, how did the process ultimately impact the community and the youth who were involved?

That year, 2014, was a really amazing moment for the city of Boston. As Mayor Menino, a 20-year incumbent, was exiting office, he was thinking about how the city could double down on authentic youth engagement. During his tenure, Menino had built a youth council that was unlike many others because it really advised the mayor and other elected officials on youth-related issues. If a city department or agency was considering a youth initiative like reimagining school lunch or improving community policing, the young council was engaged immediately. Someone in the budget office, who had attended a presentation on participatory budgeting, proposed the idea of bringing PB to Boston—it didn’t originate with me.

I was the director of Boston’s Department of Youth Engagement and Employment at the time, so when Mayor Walsh, the current mayor of Boston, was elected, he took up the mantle and authorized our department to move forward with a youth-led participatory budgeting process. We called the program Youth Lead the Change, and it empowered 12 to 25-year-olds in Boston to decide how to spend $1,000,000 of the city’s capital budget.

We could have taken participatory budgeting in a lot of different directions, but Mayor Walsh made the project’s priorities clear. We thought hard about who is most often excluded from government decisions and how to center their lived experiences. Equipping young people—and especially the most marginalized young people living in Boston—with the tools to execute a participatory budgeting project was not only a way to make our community more livable but, more importantly, it could make our community more equitable. It was a chance to make a real difference.

I’m happy to say that the City of Boston went on to win the United States Conference of Mayors City Livability Award in 2015, but it’s the impact that the program had on the community that was really profound. Harvard University did a study on Youth Lead the Change and found that the youth who were engaged in the process reported that they were more likely to vote in local and national elections, that they knew more about government and how it worked, and that they had learned and acquired new skills. They reported feeling more confident in their own abilities and more likely to volunteer for a community-based organization or walk into a public facility. In addition to the fact that folks can point to tangible change in their community, real leadership development occurs when people become involved in participatory budgeting.

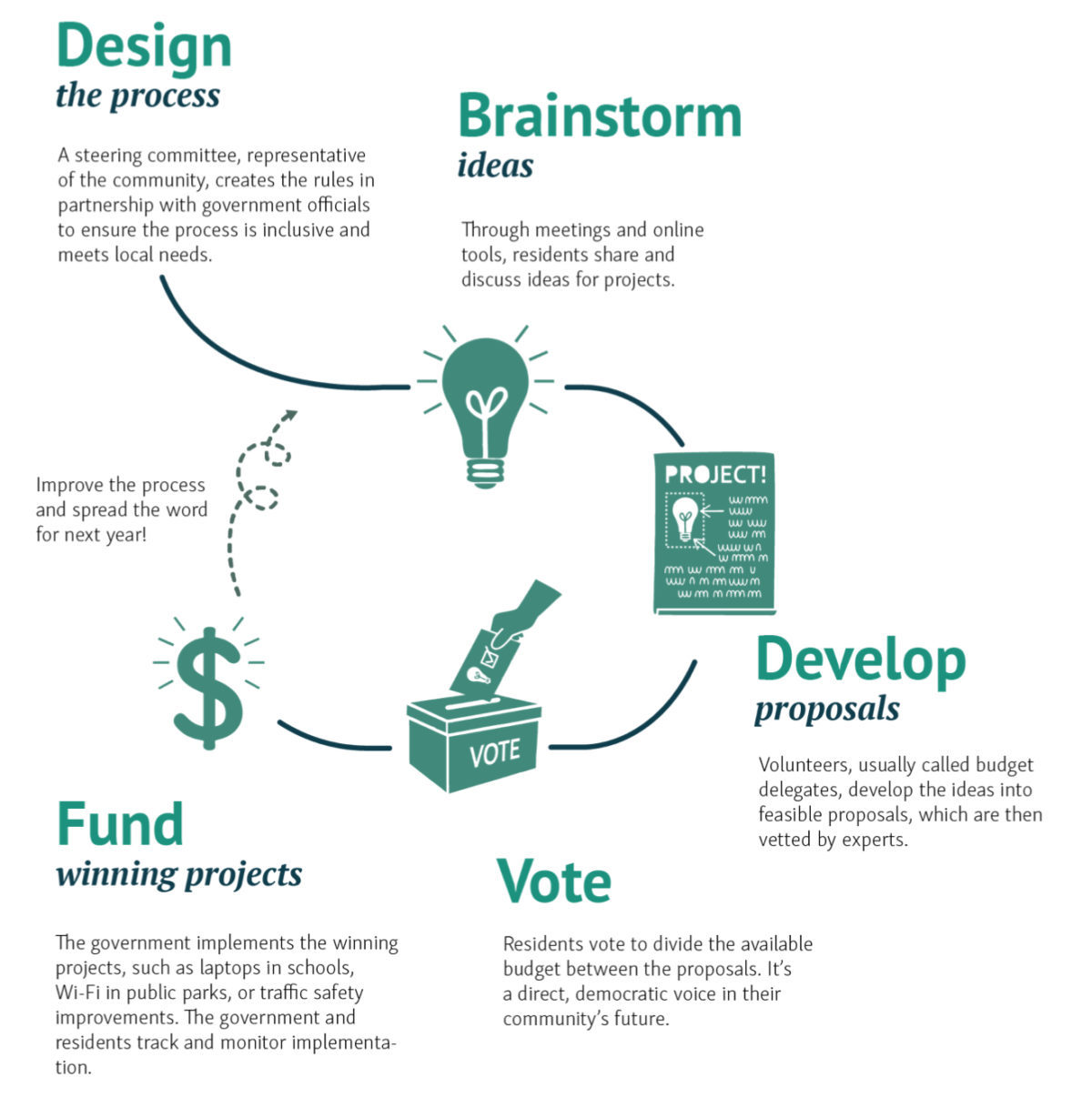

I should probably explain how the process typically works. Participatory budgeting unfolds in a couple of phases:

The first phase is one of the most important: it’s when a community steering committee comes together to write the rules that will govern the process. This initial rule-writing phase establishes transparency so that everyone knows what the process will look like, what their role will be, and what the process will decide.

After the rules are written, we enter the idea-collection phase. This is when folks have the chance to submit hundreds, if not thousands, of ideas on how to spend a portion of public funds. Typically, ideas are collected through a series of community events, at locations where people are, such as train stations, schools, markets, and even online through social media.

Once those ideas have been collected, the proposal-development phase begins. This is when community volunteers, working alongside city and agency staff, distill those ideas into practical proposals based on community need, feasibility, and impact. Once those ideas are distilled down into a workable plan, costs are identified. In some cases, proposals are merged together before they end up on the final ballot, but projects don’t make it onto the ballot unless they can really happen in communities.

One important thing to understand about participatory budgeting is that the process doesn’t identify or recommend new line items in a public budget. Instead, the process creates a space for community members to make decisions together about how already approved public funds will be used.

The projects that appear on the final ballot then enter the community-voting phase. Unlike in traditional local elections, the steering committee thinks critically about where and how the voting process will take place. Similar to the idea-collection process, voting is designed by the steering committee and may take place at a community center, a popular grocery store, a park—you name it. They really think about the goals of participatory budgeting, the folks who need to be engaged, and the best strategy for engaging those groups and individuals in the voting process.

Voting usually lasts for at least a couple of days, but in some cases it can take a week or longer. A primary goal is to make sure that everyone in the community is given an opportunity to have their voice heard and cast a vote on a project they would like to see funded. The projects that receive the most votes get funded, of course.

Read the Organizing Engagement introduction to participatory budgeting to learn more about the process →

While many of the projects were really practical and addressed things young people needed, others were wildly creative and artistic. One example was a proposal to create art walls, which was both artistic and practical. The youth involved in that project wanted to create public spaces where young artists could canvas their art but not face consequences such as arrest or jail time. They wanted these young artists to be able to express themselves without getting caught up in the juvenile justice system. The young people thought that if they could create public art walls attached to community-based organizations, young people would be able to canvas their art without being policed. The walls would also connect young artists and become spaces for community-building.

In Boston, some really amazing projects were funded. For example, one project was a park renovation that integrated accessibility structures. The young people involved in that project really thought about how to make the city more accessible—and not only for people with disabilities but for the community at large. They proposed increasing Wi-Fi access in parts of the city that young people frequented, and they proposed a mobile application that would help youth find jobs and employment opportunities.

I think that’s an example of a really wonderful project that serves many different needs from promoting public safety to keeping youth out of the juvenile justice system to building a stronger sense of community. This is an example of young people being really smart and demonstrating their leadership and understanding of what it takes to create healthy communities.

Q: As you might guess, the topic of youth leadership comes up a lot in my conversations with school and community leaders, and it seems like questions of power-sharing and control are always a central problem or—depending on how they look at it—opportunity. Most people want to help youth develop skills and capabilities so they can become effective leaders as adults, but some people think the best approach is to create a kind of adult-managed “sandbox” in which youth practice leadership in a controlled environment or perform simulated roles—I would say that mock debates or non-voting seats on a school board are two examples—while others believe that the only legitimate form of youth leadership is letting students make real decisions and take real action on real community issues. Clearly, inviting youth to figure out how to spend $1 million in a city budget is giving them genuine power and control. How do you think about youth leadership? And what happened when you let students make real decisions?

Whenever someone asks me how participatory budgeting can prepare youth to be future leaders, my first response is to say that young people are not future leaders—they’re leaders right now. If they’re given opportunities, resources, and support, youth can become catalysts for the change we need. I can’t think of any major social movement that wasn’t infused with amazing youth leadership.

If I’m going to be completely honest, most of the time young people I work with end up transforming me, not the other way around. I can think of so many amazing youth leaders I’ve encountered over the years. One young leader that comes to mind is Malachi Hernandez. Malachi grew up in the Roxbury and Dorchester neighborhoods of Boston and was involved in the art scene there. We met each other when I was working with the Mayor’s Youth Council and he was doing work related to his summer job. I got an opportunity to see him step into a leadership role and become a real ambassador who helped other young people get involved in the process.

Through his work on participatory budgeting, Malachi got the opportunity to visit the White House, meet Barack Obama, and even serve as part of the My Brother’s Keeper initiative. He became an adviser to the President on issues that were important to young men of color across the country.

“Whenever someone asks me how participatory budgeting can prepare youth to be future leaders, my first response is to say that young people are not future leaders—they’re leaders right now. If they’re given opportunities, resources, and support, youth can become catalysts for the change we need.”

A couple of years later, when I decided to apply for an opportunity to serve as a fellow with the Obama Foundation, I called Malachi to see if he would be willing to serve as a reference for me. So one of my references for the Obama Fellowship was a young person I met when he was a teenager working on Youth Lead the Change. I think that personal story alone speaks to the transformative power of participatory budgeting and genuine youth leadership. We’re not only opening doors for youth when we give them opportunities to lead, but they are developing abilities that will allow them to open doors for other people.

I can think of a few other ways to look at this issue, as well. If we want to build a building, for example, we want experts to do the work. We go out and hire architects and builders, and we would want to make sure the building is safe and that it meets all the necessary requirements. Now, if we’re talking about building healthy communities, the same rules apply. I want to involve the folks who are most proximate to that space in developing solutions that are going to be relevant for them and generations to come. And one way to do that is by centering youth engagement in the work.

Centering youth engagement doesn’t mean excluding adult participation; it means providing young people with real decision-making power and being authentic about action civics, which is a student-led approach to civics education that focuses on empowerment and applied learning. I know the idea sometimes makes adults feel vulnerable, but it doesn’t have to be a conversation about who’s included or excluded; it should be a conversation about community-building and inviting folks into the fold to make better decisions together. It should be a conversation about putting youth and adults on the same side of the table to address really complex issues.

I’m here to report that young people have the ability, the prowess, and the pragmatism to do exactly that. They also have skillsets that communities need and can build on. And I’m not just talking about the kind of government we want today; I’m also talking about the government that we want to have ten years from now. We need to be thinking about long-game strategies as well.

Developing youth leaders and putting them into positions where they have the support they need to make real, concrete, and lasting decisions in their communities is not only a testament to their abilities, but it’s putting a long-game strategy into action because young people will continue to evolve as leaders and become better prepared for future leadership opportunities.

One example that I’m really proud to highlight is the Phoenix Union High School District, where, a few years ago, one of the high schools piloted a participatory budgeting process that let young people decide how to spend some school district funds. Fast-forward to today, and now every high school in the district is using a PB process. It started with one high school and spread to the entire district. Young people in the Phoenix Union High School District now lead the PB process from beginning to end, and they’re thinking about and addressing really challenging components of the system.

For example, it’s hot in Phoenix, so these young people are thinking about hydration and water-refilling stations and accessibility to those stations so that students will be safer during the school day. They’re also thinking about art and access to art programs, and how they can bring in additional programming and support opportunities so that young people can experience electives that may not be offered in their school. These young people are coming together to determine what electives they want, and what equipment and other resources are needed to make the programs a lighter lift for their school community.

“Now every high school in the district is using a PB process. It started with one high school and spread to the entire district. Young people in the Phoenix Union High School District now lead the PB process from beginning to end, and they’re thinking about and addressing really challenging components of the system.”

One of the best things that I’ve seen happen in the Phoenix Union High School District is the forming and forging of a stronger community among the schools. A remarkable feature of their participatory budgeting process is that the Maricopa County Recorder’s Office partners with the district to run the PB process. So when a young person in the Phoenix Union High School District votes in a PB process, they are using the same ballot that they would use to vote in a traditional local or national election. What this means is that high school students in the district may have more practice voting than many adults in the community—they’ve already seen what the ballot looks like and they know how to fill it out.

I also want to mention the Safe Schools Project that we did in Brooklyn. The Brooklyn Borough President identified two school campuses and allocated half a million dollars to each campus. He then challenged young people to think about student safety and what spending allocations and school policies were needed to promote improved school safety. This was the largest pot of money ever allocated in the United States for a school-based PB process.

The young people who were involved considered a lot of things. They thought about material investments, but they also thought about policy changes. When they considered what needed to happen to foster a safe school environment, the young people decided that they needed to create student-safety councils so that they could have ongoing conversations about safety issues. That was a major policy change that resulted from the process.

We’re seeing that participatory budgeting produces a lot of transformative impacts on youth, but this is only happening because young people are being given real opportunities to assert leadership in ways that really matter.

Q: We’ve been discussing some of the effects that participatory budgeting can have on young people, but it can be a similarly transformative experience for adults. I suspect that most community members, when they first get involved in participatory budgeting, have never directly participated in a deliberative civic process, and many of them must walk away with a radically different understanding of their local government institutions and what it takes to make informed decisions in a democracy. How have you seen PB change adults and communities?

I just described how participatory budgeting has changed me, but I’ve seen a similar transformative pattern happen with many, many other people. I think the beauty of participatory budgeting is it really helps people to step outside of their own experience—to put themselves in the shoes of others—and think about issues from another perspective.

We’ve seen folks walk into a participatory budgeting process saying, for example, “I want new equipment for my child’s school.” But when they’re in that room listening to others and hearing their concerns, they walk out of the room saying, “You know, new equipment for my child’s school might be amazing, but the conditions of the school bathrooms in my neighbor’s school are actually not okay for students.” This is a real example from New York City. Even though many came into the process with other ideas, they ultimately voted to support bathroom renovations in the schools.

Then when the city officials saw adults deciding to spend money on bathroom renovations, they said, “We’re going to make sure that this issue doesn’t come up on a PB ballot again, so we’re going to renovate all of the school bathrooms so that students won’t have this experience this problem anymore.”

This is an example of broader systemic change resulting from PB, but it happened because the process helped those in government really understand the community’s funding priorities. That realization then influenced government spending priorities and resourced a really serious issue the community had identified.

“I often ask myself: How do we create opportunities for communities to develop the skills and resources they need to navigate government, so that they not only feel comfortable being in a public space, but they also feel comfortable becoming the government? Participatory budgeting can bring us a step closer to that future.”

Skill gains are another thing I mentioned earlier, and the skill gains that come through participatory budgeting are not exclusive to young people. One example I can think of is Maria Hadden. She was one of the founding board members at the Participatory Budgeting Project, but she also did some amazing community-organizing work in Chicago, Illinois. Her early involvement in participatory budgeting became one of many launching points for her political career.

Fast-forward ten years, and she’s an elected alderwoman in Chicago’s 49th ward. She was the first woman of color in the state to not only lead a participatory budgeting process, but also lead one as a public official elected by her community. I think she’s a wonderful example of the transformative power of participatory budgeting.

Another issue we should touch on is that there’s a lot of distrust in government today and a lot of concern about mismanagement of public funds, and part of the problem is that there has been a real breakdown in communication between those working in government and those in the communities they serve. As someone who worked in government for about 15 years, I feel confident saying that.

I often ask myself: How do we create opportunities for communities to develop the skills and resources they need to navigate government, so that they not only feel comfortable being in a public space, but they also feel comfortable becoming the government? Participatory budgeting can bring us a step closer to that future.

Q: Given that participatory budgeting typically uses relatively small amounts of discretionary funding in a public budget, you must get this question pretty frequently, but it seems like an important one to ask: What impact can a process have on the larger system? I know that participatory budgeting often produces ripple effects that extend far beyond the specific projects that are funded, but can you give us a few real-world examples?

We have seen participatory budgeting have a lot of effects on the larger system. In the City of Boston, for example, when we did Youth Lead the Change, youth employment was not eligible for funding through the process—only capital projects were eligible because of where the money came from in the budget. Even though that was the case, plenty of ideas were generated in the PB process that specifically focused on youth employment, and every idea went somewhere. Even if the idea wasn’t eligible for funding, it was still considered and sent to the appropriate department or division in the local government.

In this instance, many of those ideas went to the Department of Youth Engagement and Employment, which as I mentioned I was directing at the time. We listened to all the ideas generated by the PB process to redesign and re-launch the Youth Employment Program, which was a nationally acclaimed program that we were able to make even better based on the feedback and insights that young people had throughout the process. And remember, the Youth Employment Program was not eligible to receive PB funding, but the process still transformed that program.

When I think about a broader systems-change strategy, another wonderful example is Vallejo, California, which was the first citywide participatory budgeting process in the United States that was initiated after a city had declared bankruptcy.

In Vallejo, there was a strong feeling of distrust in local government. Participatory budgeting was launched alongside a sales-tax measure that sought to increase city revenue. The first year, Vallejo organized a multimillion-dollar PB process that has since been maintained at $1,000,000 or more on an ongoing basis. Community members in Vallejo not only have an opportunity to participate in government and public decision-making, but they are also rebuilding the trust that’s essential to solving the community’s problems. That’s one of the beautiful things about participatory budgeting: it’s a trust-building process that utilizes the expertise of community members to develop innovative and creative solutions.

Q: In an earlier conversation we had, you mentioned that the Participatory Budgeting Project is planning to scale up its work with youth and schools. Why do you feel that education systems, in particular, need to be a strategic priority—and not just for your organization, but for democratic decision-making and civic engagement in the United States generally?

I sincerely believe that young people are a major part of how we’ll move toward a healthier society. How we support young people and their leadership will be a crucial element of the work over the next 10, 50, or 200 years. As we consider how to deal with the climate crisis, for example, or how we keep folks politically involved, I believe that schools are a critical space.

At the Participatory Budgeting Project, we have a new strategic direction focused on supporting young leaders, as you mentioned. One part of the plan is about scaling up participatory budgeting in schools so that we can arm young leaders with skillsets and resources they’ll need to navigate government. We want them to know how to function and lead and shape that space—whether they want to run for elected office or contribute in some other way.

“In our marginalized communities, young people often hear the message, which can be passed down generationally, that they don’t belong. I believe that participatory budgeting, especially in schools, can be part of a long-term strategy to ensure that young people not only know that they belong, but that they are essential to building a healthy community.”

In our marginalized communities, in particular, young people often hear the message, which can be passed down generationally, that they don’t belong. I believe that participatory budgeting, especially in schools, can be part of a long-term strategy to ensure that young people not only know that they belong, but that they are essential to building a healthy community.

Participatory budgeting doesn’t just happen in larger cities—it can happen in rural communities, too. Merced County in California is an example. After piloting the process in two county districts, they are now bringing participatory budgeting into their schools. They’re going to start with their elementary-school partners to develop and cultivate young leaders so that they are action-civics participants by the time they graduate elementary school.

I’m really excited for these young people in Merced to have this opportunity, but what I’m really excited about is that we’ll have a generation of young leaders that have gone through this sort of civic process from the time that they were in elementary school. Just think about the kinds of skills and abilities these young people will have to move us forward as a country.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Copyright

Copyright © by Organizing Engagement and Shari Davis. All rights reserved. This interview may not be reproduced without the express written permission of the publisher. Brief quotations are allowed under Section 107 of the Copyright Act.