The Core Principles for Public Engagement were developed by the Public Engagement Principles Project, a collaboration led by the National Coalition for Dialogue and Deliberation, International Association for Public Participation, Co-Intelligence Institute, and other organizations and leaders working in the field of civic participation and engagement.

The Public Engagement Principles Project was launched in early 2009 in response to the Obama administration’s Open Government Directive memorandum, which called on all federal agencies to “ensure the public trust and establish a system of transparency, public participation, and collaboration” to create an “unprecedented level of openness in Government.” The goal of the project was to identify a foundational set of beliefs and strategies that would articulate what equitable, open, and effective public engagement looks like in practice, and what organizations and professionals in the international public-engagement field would support.

“In a strong democracy, citizens and government work together to build a society that protects individual freedom while simultaneously ensuring liberty and justice for all. Engaging people around the issues that affect their lives and their country is a key component of a strong democratic society. Public engagement involves convening diverse, representative groups of people to wrestle with information from a variety of viewpoints all to the end of making better, often more creative decisions. Public engagement aims to provide people with direction for their own community activities, or with public judgments that will be seriously considered by policy-makers and other power-holders.”

Core Principles for Public Engagement

The seven principles are described in the publication Core Principles for Public Engagement, which was published in May 2009 by the Public Engagement Principles Project’s eight-person working group. To develop the principles, the working group began with a synthesis of several sets of public-engagement principles that were then “critiqued by dozens of professionals and revised numerous times under the guidance of the core working group.” The Core Principles for Public Engagement were then endorsed by an extensive list of public-engagement organizations and professionals.

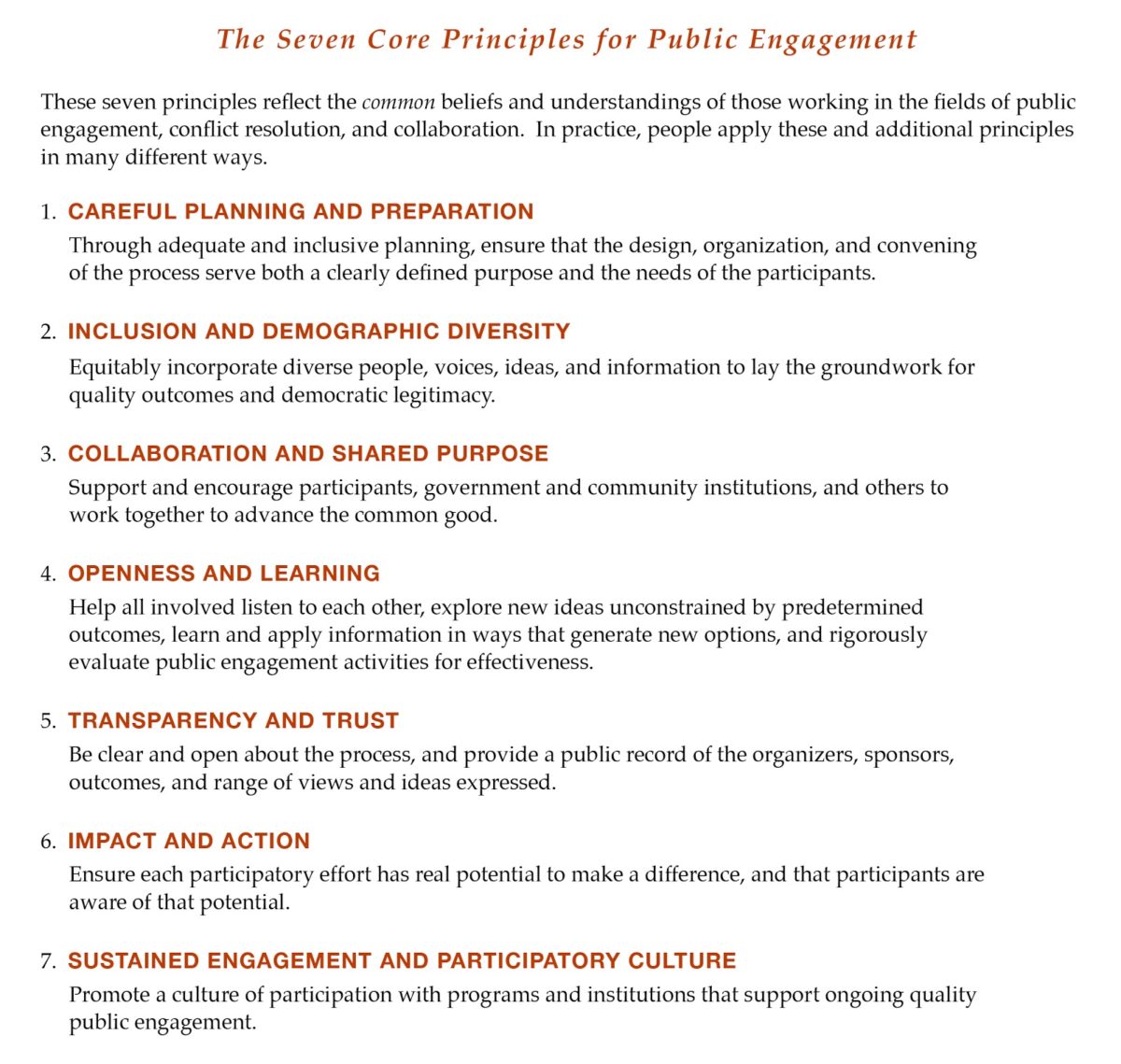

The Seven Core Principles for Public Engagement

The seven Core Principles for Public Engagement were developed for use in general civic-engagement contexts, and the strategies outlined below can be readily applied in education organizing and engagement contexts. The following descriptions from Core Principles for Public Engagement are presented here in full with permission from the National Coalition for Dialogue and Deliberation.

Principle #1: Careful Planning and Preparation

Through adequate and inclusive planning, ensure that the design, organization, and convening of the process serve both a clearly defined purpose and the needs of the participants.

In high-quality engagement: Participation begins when stakeholders, conveners, and process experts engage together, with adequate support, in the planning and organizing process. Together they get clear on their unique context, purpose, and task, which then inform their process design as well as their venue selection, set-up, and choice of participants. They create hospitable, accessible, functional environments and schedules that serve the participants’ logistical, intellectual, biological, aesthetic, identity, and cultural needs. In general, they promote conditions that support all the qualities on this list.

What to avoid: Poorly designed programs that do not fit the specific needs and opportunities of the situation, or that are run by untrained, inexperienced, or ideologically biased organizers and programs. Such programs fail to achieve the desired objectives and disrespect or exclude relevant stakeholder groups. Public meetings are held in inaccessible, confusing venues, with inflexible schedules that do not provide adequate time for doing what needs to be done. Logistical, class, racial, and cultural barriers to participation are left unaddressed, effectively sidelining marginalized people and further privileging elites, majorities, “experts,” and partisan advocates.

Principle #2: Inclusion and Demographic Diversity

Equitably incorporate diverse people, voices, ideas, and information to lay the groundwork for quality outcomes and democratic legitimacy.

In high-quality engagement: Conveners and participants reflect the range of stakeholder or demographic diversity within the community or on the issue at hand. Where representatives are used, the nature, source, and any constraints on their representative authority are clearly identified and shared with participants. Alternatively, participants are randomly selected to represent a microcosm of the public. Participants have the opportunity to grapple with data and ideas that fairly represent different perspectives on the issue. Participants have equal status in discussions, and feel they are respected and their views are welcomed, heard, and responded to. Special effort is made to enable normally marginalized, silent, or dissenting voices to meaningfully engage—and fundamental differences are clarified and honored. Where necessary, anonymity is provided to enable important contributions.

What to avoid: Participants are mostly “the usual suspects”—perhaps with merely token diversity added. Biased information is presented, and expert testimony seems designed to move people in a specific direction. People do not feel that it is safe to speak up, or they have little chance to do so—and if they do, there is little sign that they are actually heard. Participants, stakeholders, or segments of the public feel their interests, concerns, and ideas are suppressed, ignored, or marginalized. Anonymity is used to protect abuses of power, not vulnerable critics.

Principle #3: Collaboration and Shared Purpose

Support and encourage participants, government and community institutions, and others to work together to advance the common good.

In high-quality engagement: Organizers involve public officials, “ordinary” people, community leaders, and other interested and/or affected parties as equal participants in ongoing discussions where differences are explored rather than ignored, and a shared sense of a desired future can emerge. Organizers pay attention to the quality of communication, designing a process that enables trust to be built among participants through dialogue, permits deliberation of options, and provides adequate time for solutions to emerge and evolve. People with different backgrounds and ideologies work together on every aspect of the program—from planning and recruiting, to gathering and presenting information, and all the way through to sharing outcomes and implementing agreed-upon action steps. In government-sponsored programs, there is good coordination among various agencies doing work relevant to the issue at hand.

What to avoid: Unresponsive power-holders deliver one-way pronouncements or preside over hostile, disrespectful, or stilted conversations. Patronizing experts and authorities feel they already have all the answers and “listen” only to appease. Engagement has no chance of impacting policy because relevant decisions have already been made or are already in the pipeline, or because those in power are not involved or committed. Loud or mainstream voices drown out all others, while personal stories, emotions, and unpopular opinions are not welcomed. References to isolated data or studies are used to suppress other forms of input. Involvement feels pointless to participants, lacking clear purpose or a link to action.

Principle #4: Openness and Learning

Help all involved listen to each other, explore new ideas unconstrained by predetermined outcomes, learn and apply information in ways that generate new options, and rigorously evaluate public engagement activities for effectiveness.

In high-quality engagement: Skilled, impartial facilitators and simple guidelines encourage everyone involved to share their views, listen, and be curious in order to learn things about themselves, each other, and the issues before them. Shared intention and powerful questions guide participants’ exploration of adequate, fair, and useful information—and of their own disagreements—in an open and respectful atmosphere. This exploratory atmosphere enables them to delve more deeply into complexities and nuances, and thereby generate new understandings, possibilities, and/or decisions that were not clear when their conversation began. There is an appropriate balance between consulting (a) facts and expertise and (b) participants’ experience, values, vision, intuition, and concerns. Participants and leaders take away new skills and approaches to resolving conflicts, solving problems, and making decisions. Careful review, evaluation, and a spirit of exploration and innovation improve subsequent engagement work and develop institutional and community capacity.

What to avoid: “Window dressing” public exercises that go through the motions required by law or the dictates of public relations before announcing a predetermined outcome. Participants get on soapboxes or are repressed; fight or conform; get overridden or overwhelmed; and are definitely not listening to each other. Facilitation is weak or too directive, interfering with people’s ability to communicate with each other openly, adjust their stances, and make progress. Assertive, mainstream, and official voices dominate. Available information is biased, scanty, overwhelming, or inaccessible—and experts lecture rather than discuss and clarify. Lack of time or inflexible process make it impossible to deal with the true complexity of the issue. Organizers and facilitators are too busy, biased, or insecure to properly review and evaluate what they’ve done.

Principle #5: Transparency and Trust

Be clear and open about the process, and provide a public record of the organizers, sponsors, outcomes, and range of views and ideas expressed.

In high-quality engagement: Relevant information, activities, decisions, and issues that arise are shared with participants and the public in a timely way, respecting individuals’ privacy where necessary. Process consultants and facilitators are helpful and realistic in describing their place in the field of public engagement and what to expect from their work. People experience planners, facilitators, and participants with official roles as straightforward, concerned, and answerable. Members of the public can easily access information, get involved, stay engaged, and contribute to the ongoing evolution of outcomes or actions the process generates.

What to avoid: It is hard, if not impossible, to find out who is involved, what happened, and why. Research, advocacy, and answerability efforts are stymied. Participants, the public, and various stakeholders suspect hidden agendas and dubious ethics. Participants not only don’t trust the facilitators but are not open about their own thoughts and feelings.

Principle #6: Impact and Action

Ensure each participatory effort has the potential to make a difference, and that participants are aware of that potential.

In high-quality engagement: People believe—and can see evidence—that their engagement was meaningful, influencing government decisions, empowering them to act effectively individually and/or together, or otherwise impacting the world around them. Communications (of media, government, business, and/or nonprofits involved) ensure the appropriate publics know the engagement is happening and talk about it with each other. Convening organizations or agencies maximize the quality and use of the input provided, and report back to participants and the public about how data from the program influenced their decisions or actions. The effort is productively linked to other efforts on the issue(s) addressed. Because diverse stakeholders understand, are moved by, and act on the findings and recommendations of the program, problems get solved, visions are pursued, and communities become more vibrant, healthy, and successful—despite ongoing differences.

What to avoid: Participants have no confidence that they have had any meaningful influence—before, during, or after the public-engagement process. There is no follow-through from anyone, and hardly anyone knows it happened, including other people and groups working on the issue being addressed. Participants’ findings and recommendations are inarticulate, ill-timed, or useless to policy-makers—or seem to represent the views of only a small unqualified group—and are largely ignored or, when used, are used to suppress dissent. Any energy or activity catalyzed by the event quickly wanes.

Principle #7: Sustained Engagement and Participatory Culture

Promote a culture of participation with programs and institutions that support ongoing quality public engagement.

In high-quality engagement: Each new engagement effort is linked intentionally to existing efforts and institutions—government, schools, civic and social organizations, etc.—so quality engagement and democratic participation increasingly become standard practice. Participants and others involved in the process not only develop a sense of ownership and buy-in, but gain knowledge and skills in democratic methods of involving people, making decisions, and solving problems. Relationships are built over time and ongoing spaces are created in communities and online, where people from all backgrounds can bring their ideas and concerns about public affairs to the table and engage in lively discussions that have the potential to impact their shared world.

What to avoid: Public engagements, when they occur, are one-off events isolated from the ongoing political life of society. For most people, democracy means only freedoms and voting and perhaps writing a letter to their newspaper or representative. For activists and public officials, democracy is the business-as-usual battle and behind-the-scenes maneuvering. Few people—including public officials—have any expectation that authentic, empowered public participation is possible, necessary, forthcoming, or even desirable. Privileged people dominate, intentionally or unintentionally undermining the ability of marginalized populations to meaningfully participate.

Acknowledgments

Organizing Engagement thanks Courtney Breese and Keiva Hummel for their contributions to improving this introduction, and the National Coalition for Dialogue and Deliberation for permission to reproduce excerpts and images from Core Principles for Public Engagement.

Creative Commons

This work by Organizing Engagement is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. When excerpting, adapting, or republishing content from this resource, users should cite the source texts and confirm that all quotations and excerpts are accurately presented.