In 2013, the Southwest Educational Development Laboratory (now part of the American Institutes for Research) published, in association with the U.S. Department of Education, Partners in Education: A Dual Capacity-Building Framework for Family-School Partnerships.

Created by Karen Mapp, with support from Paul Kuttner, the Dual Capacity-Building Framework quickly became one of the most influential models in the field of youth, family, and community engagement in education. The framework was informed by decades of research indicating that strong family-school partnerships can significantly improve learning and long-term educational outcomes for students.

In 2019, Karen Mapp—working in collaboration with Marissa Alberty, Eyal Bergman, and the Institute for Educational Leadership—released an updated version (Version 2) of the Dual Capacity-Building Framework for Family-School Partnerships. The revised version was published at dualcapacity.org, a website developed to “bring the framework to life and help put it into practice across the United States.”

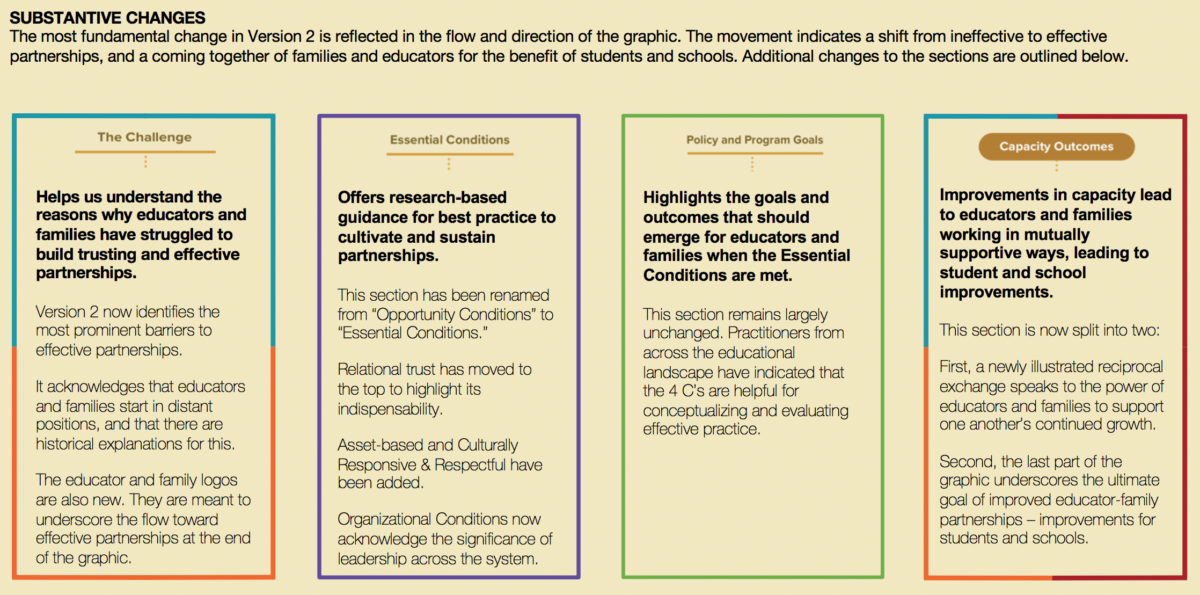

The modifications made to the framework were based on feedback received from organizations and practitioners who had been using the framework in their districts, schools, and communities, including responses to a survey of more than 1,000 participants of the 2017 Institute for Educational Leadership’s National Family and Community Engagement Conference.

“The Framework builds on existing research suggesting that partnerships between home and school can only develop and thrive if both families and staff have the requisite collective capacity to engage in partnership. Many school and district family-engagement initiatives focus solely on providing workshops and seminars for families on how to engage more effectively in their children’s education. This focus on families alone often results in increased tension between families and school staff: families are trained to be more active in their children’s schools, only to be met by an unreceptive and unwelcoming school climate and resistance from district and school staff to their efforts for more active engagement. Therefore, policies and programs directed at improving family engagement must focus on building the capacities of both staff and families to engage in partnerships.”

Karen Mapp and Paul Kuttner, Partners in Education: A Dual Capacity-Building Framework for Family-School Partnerships

The Dual Capacity-Building Framework for Family-School Partnerships advances a simple but instrumental premise: effective family-school partnerships can only occur when the requisite capacity exists both inside and outside the school system. According to Mapp and Kuttner (2013), “The limited capacity of the various stakeholders to partner with each other and to share the responsibility for improving student achievement and school performance is a major factor in the relatively poor execution of family engagement initiatives and programs over the years.”

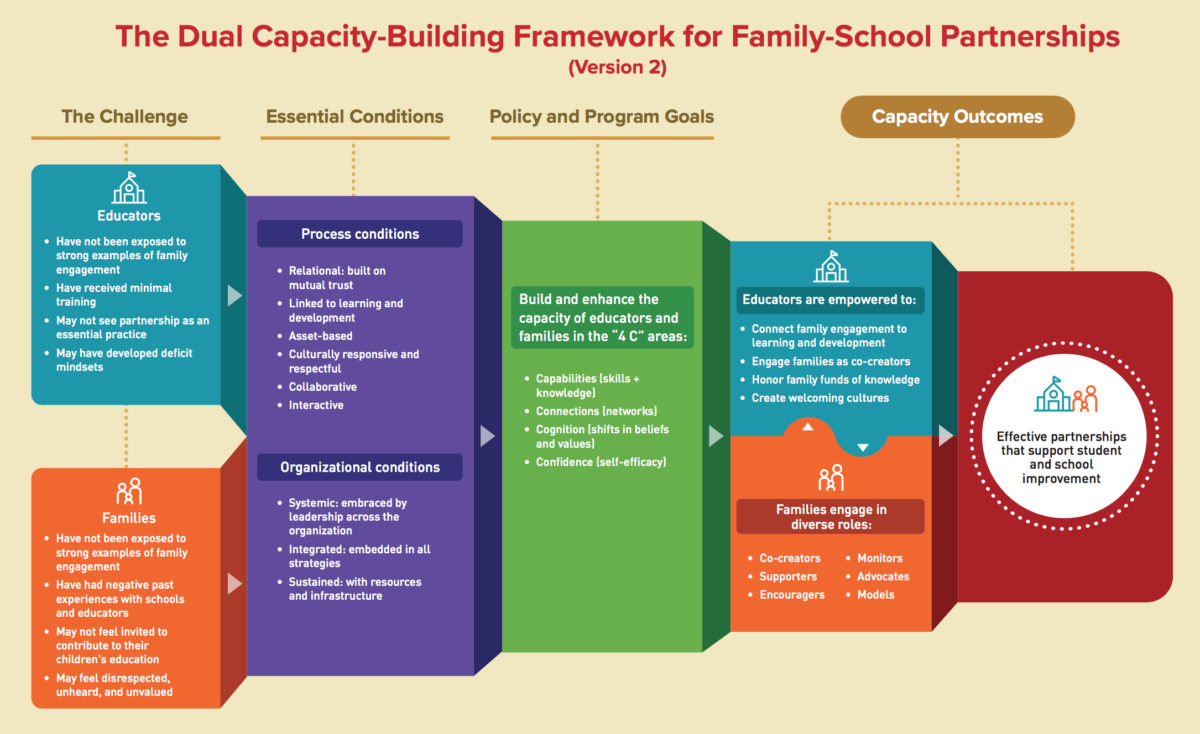

Developed by Karen Mapp, the original version of the Dual Capacity-Building Framework for Family-School Partnerships was published in 2013 and quickly became one of the most influential models in the field of youth, family, and community engagement in education. While Version 2 features several substantive changes to the model and a redesigned graphic, the four foundational components of the original model—describing challenges, conditions, goals, and outcomes—remain in the new version released in 2019. Source: Partners in Education: A Dual Capacity-Building Framework for Family-School Partnerships

In other words, successful engagement requires both educators and family members to develop essential beliefs, knowledge, skills, confidence, social relationships, and other capacities. When school leaders and teachers don’t have the necessary capacity, the school system cannot function in ways that equitably support a partnership-based approach to educating children, and when parents and other family members are not informed about the school system or empowered to advocate for a more equitable or effective education for their children, school systems are more likely to fall short of meeting their children’s needs.

While the framework is focused on partnerships between educators and families, and specifically partnerships that are more directly connected to classroom learning experiences, it nevertheless provides useful guidance for partnerships between educators and youth or between schools and community organizations.

Released in 2019, Version 2 of the Dual Capacity-Building Framework for Family-School Partnerships showcases a redesigned graphic. Abandoning the vertical orientation of the original 2013 version, the revised framework is presented horizontally to better illustrate the “shift from ineffective to effective partnerships” and avoid the hierarchical connotations people tend to associate with vertical models. The new version also features several content modifications based on feedback from practitioners and new insights from engagement research and practice. Source: dualcapacity.org

Dual Capacity-Building Framework for Family-School Partnerships

In Partners in Education (2013), which also features three case studies, Mapp and Kuttner describe the four main components of the original model:

- A description of the capacity challenges that must be addressed to support the cultivation of effective home-school partnerships (The Challenge).

- An articulation of the conditions integral to the success of family-school partnership initiatives and interventions (Opportunity Conditions).

- An identification of the desired intermediate capacity goals that should be the focus of family engagement policies and programs at the federal, state, and local level (Policy and Program Goals).

- A description of the capacity-building outcomes for families and for school and program staff (Family and Staff Capacity Outcomes).

The original 2013 version of the Dual Capacity-Building Framework for Family-School Partnerships was presented vertically, with “The Challenge” featured at the top and “Family and Staff Capacity Outcomes” at the bottom. Version 2 (2019) presents the framework horizontally to better illustrate the “shift from ineffective to effective partnerships” and avoid the hierarchical connotations that people tend to associate with vertically presented models. The new version also features several content modifications that are discussed below.

Between the publication of Karen Mapp’s original Dual Capacity-Building Framework for Family-School Partnerships in 2013 and the release of Version 2 in 2019, numerous districts, schools, and organizations used the framework to guide their work on family-school engagement. Version 2 incorporates modifications based on practitioner feedback, survey data, and advances in research and practice. This illustration describes the substantive modifications made to the revised framework. Source: dualcapacity.org

The Challenge

According to Mapp and Kuttner (2013), “A common refrain from educators is that they have a strong desire to work with families from diverse backgrounds and cultures and to develop stronger home-school partnerships of shared responsibility for children’s outcomes, but they do not know how to accomplish this. Families, in turn, can face many personal, cultural, and structural barriers to engaging in productive partnerships with teachers. They may not have access to the social and cultural capital needed to navigate the complexities of the U.S. educational system, or they may have had negative experiences with schools in the past, leading to distrust or to feeling unwelcomed.”

The challenge, therefore, is to integrate capacity-building opportunities into school and community policies, programs, and practices for both educators and family members.

The Challenge section helps educators, families, and community members “understand the reasons why educators and families have struggled to build trusting and effective partnerships.” Version 2 of the framework identifies some of the most prominent barriers to effective family-school partnerships that have been shaped by historical forces in public education and society at large:

Educators

- Have not been exposed to strong examples of family engagement

- Have received minimal training

- May not see partnership as an essential practice

- May have developed deficit mindsets

Families

- Have not been exposed to strong examples of family engagement

- Have had negative past experiences with schools and educators

- May not feel invited to contribute to their children’s education

- May feel disrespected, unheard, and unvalued

Essential Conditions

The Dual Capacity-Building Framework for Family-School Partnerships (Version 2) describes two foundational components—or “Essential Conditions”—that are required for effective family-school partnerships. “Research suggests,” Mapp and Kuttner (2013) write, “that certain process conditions must be met for adult participants to come away from a learning experience not only with new knowledge but with the ability and desire to apply what they have learned. Research also suggests important organizational conditions that have to be met in order to sustain and scale these opportunity efforts across districts and groups of schools.”

There are two Essential Conditions categories: Process Conditions refer to “the series of actions, operations, and procedures that are part of any activity or initiative,” and Organizational Conditions refer to how districts, schools, or educational programs are organized to support family-school partnerships in ways “that are coherent and aligned with educational improvement goals, sustained over time, and spread across the district” (Partners in Education, 2013).

Process Conditions

Effective Process Conditions have the following six features:

1. Processes should be relational and built on mutual trust

In many schools, family programming rarely provides either sufficient time or a conducive context for educators to build trusting, understanding, and respectful relationships with parents and other family members. In the absence of strong relationships, for example, school staff may be more likely to make inaccurate, unhelpful, or even harmful assumptions about students and their families, and students and families may be more likely to make similar assumptions about the school’s administrators and educators.

Relational strategies are particularly important in communities with a history of distrust, resentment, tension, or conflict between families and schools, or when there are significant racial or cultural divides in the community. Importantly, strong relationships are motivating—when families feel that educators understand, trust, and respect them, they are more likely to participate in school activities or support their child’s education at home.

As Mapp and Kuttner (2013) observe, “Mailings, automated phone calls, and even incentives like meals and prizes for attendance do little to ensure regular participation of families.” While communication is essential, communication alone will not increase family participation, and schools that want to improve family engagement and participation should create regular opportunities for educators and families to learn about one another through dialogue and collaboration.

2. Processes should be connected to student learning and development

Research indicates that “families and school staff are more interested in and motivated to participate in events and programs that are focused on enhancing their ability to work as partners to support children’s cognitive, emotional, physical, and social development as well as the overall improvement of the school” (Partners in Education, 2013). Far too often, school-organized family events and programs are unrelated to what their children are learning in school, which Mapp and Kuttner argue is a missed opportunity.

Instead, school leaders and teachers should integrate academic connections into family programming by creating more opportunities for parents and other family members to learn about the school’s curriculum, instructional practices, and academic and developmental goals for students. Specific examples might include intensive, multi-day orientation programs that educate new students and families about school policies and educational opportunities; tours and volunteer programs that allow family members to observe and ask questions about school programs; “parent universities” that provide educational programs to family members on an array of topics (e.g., dealing with bullying, preventing substance abuse, helping with homework, navigating gender or cultural identities, planning for college, etc.); or leadership-development programs that teach parents and other family members skills that will help them become stronger advocates for their children or more visible public supporters of their school.

3. Processes should be asset-based

A “deficit-based” view of students and families focuses on perceived weaknesses, shortcomings, or deficiencies, while an “asset-based” approach emphasizes the strengths that students and families already possess. Deficit-based perceptions of students and families are often driven by assumptions, misperceptions, and stereotypes—that students are not succeeding in school because they are unmotivated and lazy, for example, or that families from a certain neighborhood don’t care about their child’s education—and asset-based engagement processes intentionally counteract these “deficit narratives” by highlighting, valuing, and building on the skills, abilities, interests, or cultural backgrounds of students and families.

Because asset-based processes work both ways—when educators adopt a more positive view of students and families, families usually develop a more positive view of educators—they can also help to rebuild mutual trust between schools and their communities by disrupting multigenerational cycles of distrust, anger, and resentment that can take hold if families experience, year after year, disparaging comments, disrespectful behavior, inequitable programs, and other forms of mistreatment or neglect. *New in Version 2

4. Processes should be culturally responsive and respectful

Culturally responsive engagement strategies demonstrate an awareness and understanding of cultural differences based on race, ethnicity, nationality, language, and other forms of identity, while also valuing, honoring, and affirming those diverse cultural perspectives and backgrounds. Culturally responsive engagement processes typically require educators, students, and families to be open about and mindful of their cultural perspectives, values, and biases, and to listen and communicate across cultural differences with intentionality and respect.

Culturally responsive engagement strategies often challenge default educational conventions that prioritize one set of values over others. For example, culturally responsive engagement may challenge behavioral standards and disciplinary policies that are based on white middle-class expectations that disproportionately and unfairly punish low-income students and students of color, or they may challenge the assumption that professional educators know more than parents, and therefore parents should let educators make all the decisions about how their children are educated. *New in Version 2

5. Processes should be collaborative

Mapp and Kuttner (2013) argue that capacity-building programs need to engage educators and families in collaborative projects and learning opportunities—i.e., programs in which educators and family members learn and work together, rather than separately. While offering distinct learning programs for teachers and for parents may provide some value, collaborative learning opportunities can be transformative when it comes to activating family-school partnerships that positively impact developmental, social, and educational outcomes for students. When educators and family members learn together and work together, it “builds social networks, connections, and, ultimately, the social capital of families and staff in the program.”

6. Processes should be interactive

In many school programs, families receive prepared information from educators, and family-educator interaction is often limited to questions and answers. According to Mapp and Kuttner (2013), “Existing family engagement strategies often involve providing lists of items and activities for teachers to use to reach out to families and for families to do with their children,” but this lack of interactive learning represents a missed opportunity when it comes to building family-school partnerships. Interactivity occurs when “participants are given opportunities to test out and apply new skills.” While acquiring new information and knowledge is essential to the capacity-building process, adult learning is most effective when participants can “practice what they have learned and receive feedback and coaching from each other, peers, and facilitators.”

Discussion: Developmental vs. Service Orientation

In Partners in Education (2013), Mapp and Kuttner make a distinction between processes that adopt a developmental orientation and those that have a service orientation. A school program with a developmental orientation will “focus on building the intellectual, social, and human capital of stakeholders engaged in the program” by “empowering and enabling participants to be confident, active, knowledgeable, and informed stakeholders in the transformation of their schools and neighborhoods.” On the other hand, programs with a service orientation will provide services and assistance but not build capacity. Put another way, development-oriented programs proactively teach people how to solve problems, while service-oriented programs attempt to solve problems for people.

Organizational Conditions

Effective Organizational Conditions share the following three features:

1. Family-school partnerships should be systemic

In many cases, family engagement is not part of the long-term strategic goals for the school, and therefore cultivating family-school partnerships are not viewed as a priority by educators and staff. Mapp and Kuttner (2013) argue that effective family-school partnerships need to be “purposefully designed as core components of educational goals such as school readiness, student achievement, and school turnaround.” According to Version 2, systemic family-school partnerships also need to be “embraced by leadership across the organization.”

2. Family-school partnerships should be integrated

In many schools, family engagement is considered an optional or non-essential practice—it’s not integrated into the day-to-day operation and activities of the school, for example, and it’s not a formal or expected component of a teacher’s job description. Consequently, family engagement, if it is done at all, tends to be relegated to add-on programs that typically serve only a small subpopulation of students and families and that are overseen by a single staff person or small team. Mapp and Kuttner (2013) argue that effective family-school partnerships need to be “embedded into structures and processes such as training and professional development, teaching and learning, curriculum, and community collaboration.”

3. Family-school partnerships should be sustained

Many family engagement programs are funded by short-term grants (and are therefore often discontinued when the money runs out) or the programs are among the first to be cut when a budget crisis arises (in part because they are often perceived as non-essential). Yet family-school partnerships must be sustained over time to be effective, which requires that they are adequately staffed and resourced, that they are supported by multiple funding streams, and that they are built into the “infrastructure” of a school—meaning, for example, that space in the school facility is provided for family-engagement activities, policies require staff to engage families on a daily or routine basis, and administrators and teachers are encouraged and authorized to do family-engagement work.

Policy and Program Goals (The 4Cs)

Largely unchanged in Version 2, the Dual Capacity-Building Framework for Family-School Partnerships identifies four policy and program goals—called the “4Cs”—that should inform a school’s capacity-building strategy for family engagement. Additional detail can be found at dualcapacity.org.

1. Capabilities (Human Capital—Skills and Knowledge)

Administrators, educators, and staff need to know their students and families well, including any struggles and barriers they may face when it comes to participating in school programs or supporting a child’s education at home. They also need relevant professional skills, whether its general skills such as cultural competency (the ability to recognize, understand, and appropriately navigate cultural differences) or specific technical skills (such as how to conduct a successful home visit).

Families, on the other hand, need to know how their child’s school works, including information about how students are assessed and graded, what their children will be learning and what the academic standards are, how they can do to encourage and support their children academically, and what policies apply to them and their children. In addition to information about the school, families also need a variety of skills—whether it’s advocating for specialized services, helping with homework, or coordinating a parent group—that the school can encourage and develop through collaborative learning programs with educators.

2. Connections (Social Capital—Relationships and Networks)

According to Mapp and Kuttner (2013), “Staff and families need access to social capital through strong, cross-cultural networks built on trust and respect. These networks should include family-teacher relationships, parent-parent relationships, and connections with community agencies and services.” In the context of family-school partnerships, isolation and disconnection can be disempowering. Family members not only need to develop understanding, trusting, and respectful relationships with educators, but they also need relationships and connections with other families and community-based organizations.

3. Confidence (Self-Assurance and Self-Efficacy)

Family-school partnerships often fail to emerge or succeed due to a lack of confidence—on the part of both educators and families. In some cases, it may be a discomfort with racial or cultural differences that causes a teacher or parent to avoid interaction, while in other cases it may be a relative lack of formal education that makes parents less secure in their ability to support their child academically. Whatever the cause, both educators and family members need to develop the self-assurance and self-efficacy required to build relationships and work together effectively, especially across racial, cultural, and socioeconomic divides.

4. Cognition (Assumptions, Beliefs, and Worldviews)

Developing capabilities, connections, and confidence often requires that certain assumptions, beliefs, or perspectives are either present or transformed. A teacher is unlikely to engage parents in respectful ways if that teacher assumes the parents are insufficiently involved in their child’s education, for example, while parents will be less motivated to speak up if they don’t believe that administrators and teachers value their perspective. If teachers don’t believe that family engagement is part of their job, they are unlikely to take the steps required to build relationships with parents; and if parents think that it’s the school’s job alone to educate their children, they will be less likely to provide the at-home support their children may need. In these cases, potentially harmful assumptions, stereotypes, and beliefs will need to be challenged and replaced with more positive mindsets and perspectives.

Capacity Outcomes

The Dual Capacity-Building Framework for Family-School Partnerships also describes the desired outcomes that will result from a sustained commitment to developing both individual and collective capacity: effective partnerships that support student and school improvement.

Version 2 also identifies the following outcomes for educators and families:

Educators will be able to:

- Connect family engagement to learning and development

- Engage families as co-creators

- Honor family funds of knowledge

- Create welcoming cultures

Families will be able to engage in diverse roles as:

- Co-creators

- Supporters

- Encouragers

- Monitors

- Advocates

- Models

Acknowledgments

Organizing Engagement thanks Karen Mapp and Paul Kuttner for their contributions to improving this introduction.

References

Mapp, K. & Kuttner, P. (2013). Partners in Education: A Dual Capacity-Building Framework for Family-School Partnerships. Austin, TX: Southwest Educational Development Laboratory in association with the U.S. Department of Education.

Creative Commons

This work by Organizing Engagement is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. When excerpting, adapting, or republishing content from this resource, users should cite the source texts and confirm that all quotations and excerpts are accurately presented.