The Equity Literacy framework was developed Paul Gorski, an educator, author, and educational activist who founded the Equity Literacy Institute in 2018, and Katy Swalwell, a teacher-educator, scholar, and activist currently teaching at Iowa State University. Equity Literacy is described in a set of documents, articles, and book chapters—many of which are available on the Equity Literacy Institute website—that articulate the framework’s foundational definitions, principles, orientations, and approaches.

Gorski and Swalwell developed the framework following, in Gorski’s words, “careful consideration of the strengths and limitations of existing frameworks for attending to diversity in schools and other organizations and systems,” approaches that Gorski observed often “mask the inequities that cause educational disparities.”

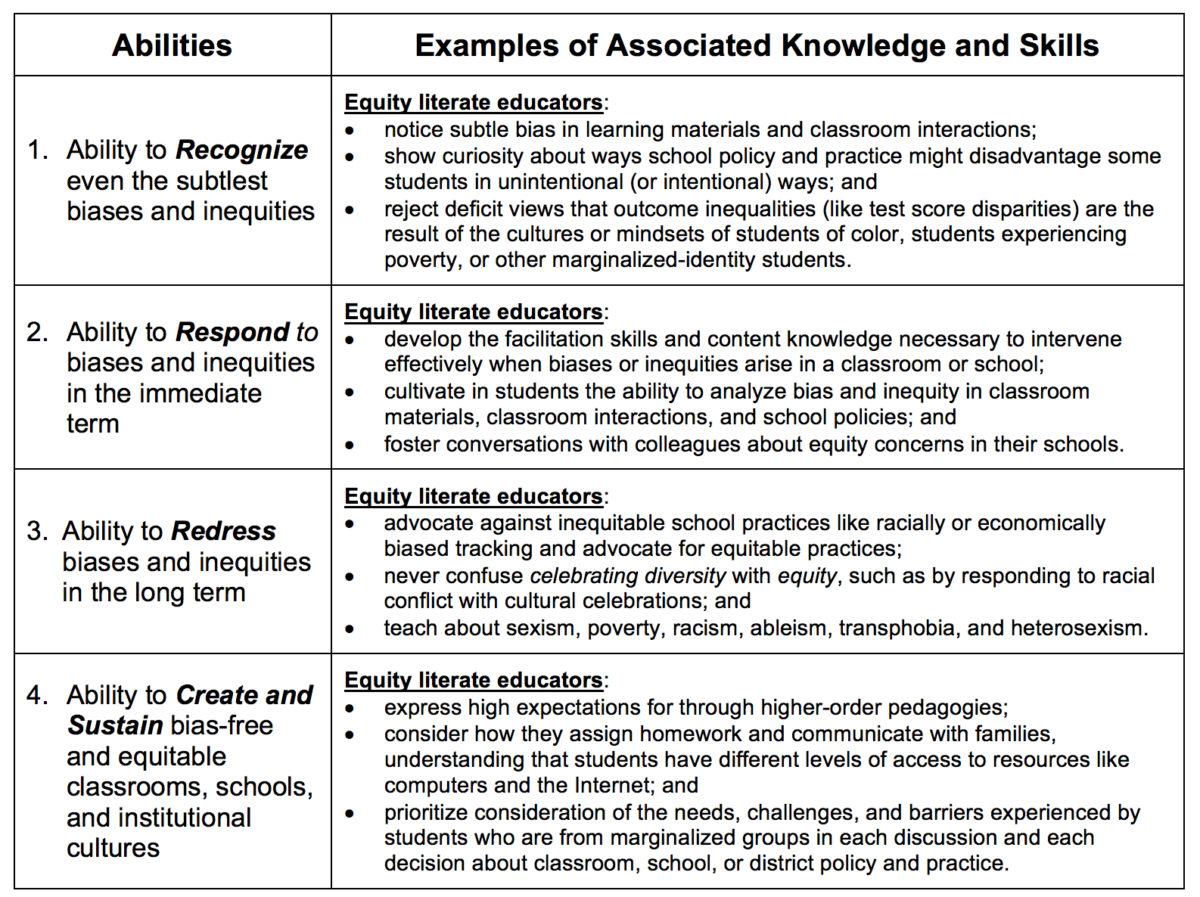

“Equity literacy is a framework for cultivating the knowledge and skills that enable us to be a threat to the existence of inequity in our spheres of influence. More than cultural competence or diversity awareness, equity literacy prepares us to see even subtle ways in which access and opportunity are distributed unfairly across race, class, gender identity, sexual orientation, (dis)ability, language, and other factors. By recognizing and deeply understanding these conditions, we are prepared to respond to inequity in transformational ways in the immediate term. We also strengthen our ability to foster longer-term change by redressing the bigger institutional and societal conditions that produce the everyday manifestations of inequity.”

Paul Gorski, Equity Literacy: Definitions and Abilities

For local leaders, organizers, and facilitators, the Equity Literacy framework provides a clearly articulated, no-nonsense approach to advancing equity in schools and communities. The framework is grounded in a rejection of “deficit ideology,” which Gorski defines as “a worldview that explains and justifies outcome inequalities—standardized test scores or levels of educational attainment, for example—by pointing to supposed deficiencies within disenfranchised individuals,” and that “discounts sociopolitical context, such as the systemic conditions (racism, economic injustice, and so on) that grant some people greater social, political, and economic access.” Equity literacy can help local organizing and engagement leaders maintain a focus on addressing the underlying structural forces, systemic barriers, and opportunity gaps that create and perpetuate inequities in schools and communities.

In a 2016 article in the magazine School Administrator, Gorski discusses the intersection of equity literacy and family engagement:

“Consider family involvement. We know that, generally, low-income parents attend family involvement events at their children’s schools less often than wealthier parents. With troubling consistency, I come across well-meaning teachers and administrators who misinterpret this reality through a deficit lens. If only those parents cared more. When we misinterpret in this way, we render ourselves equity-illiterate. Equity cannot arise from bias.

A structural view allows me to consider the problem with deeper understanding. I start by wondering about my own complicity. Do I design opportunities for family engagement that are accessible to parents who work multiple jobs, often including evening jobs, who don’t have paid leave, who may not have transportation, who might struggle to afford child care? Do the policies and practices I support mitigate or exacerbate these inequities? Do they redistribute access or punish people for their lack of access?

In the end, there is no path to equity not grounded in this structural view. When we strengthen our equity literacy, when we understand that educational outcome disparities can be traced almost entirely to structural barriers in and out of schools rather than to moral deficiencies or grit shortages in families experiencing poverty, we position ourselves to create equitable policy and practice.”

The following sections, republished here in full with permission from Paul Gorski and the Equity Literacy Institute, provide an introduction to the framework. For those interested in learning more about Equity Literacy, we also recommend the following readings:

- Equity Literacy: Definitions and Abilities

- Equity Literacy: Principles on Students Experiencing Poverty

- Five Approaches to Equity: Toward a Transformative Orientation

- Five Paradigm Shifts for Equitable Educators

- Paradigm Adjustments for Well-Intended White Educators

Equity Literacy Basic Principles

According to Gorski, “An important aspect of equity literacy is its insistence on maximizing the integrity of transformative equity practice. We must avoid being lulled by popular ‘diversity’ approaches and frameworks that pose no threat to inequity—that sometimes are popular because they are no real threat to inequity. The basic principles of equity literacy help us ensure we keep a commitment to equity at the center of our equity work and the broader equity conversation.”

The eight basic principles of equity literacy:

- The Direct Confrontation Principle: There is no path to equity that does not involve a direct confrontation with inequity. There is no path to racial equity that does not involve a direct confrontation with interpersonal, institutional, and structural racism. “Equity” approaches that fail to directly confront inequity play a significant role in sustaining inequity.

- The “Poverty of Culture” Principle: Inequities are primarily power and privilege problems, not primarily cultural problems. Equity requires power and privilege solutions, not just cultural solutions. Frameworks that attend to diversity purely in vague cultural terms, like the “culture of poverty,” are no threat to inequity.

- The Equity Ideology Principle: Equity is more than a list of practical strategies. It is a lens and an ideological commitment. There are no practical strategies that will help us develop equitable institutions if we are unwilling to deepen our understandings of equity and inequity.

- The Prioritization Principle: Each policy and practice decision should be examined through the question, “How will this impact the most marginalized members of our community?” Equity is about prioritizing their interests.

- The Redistribution Principle: Equity requires the redistribution of material, cultural, and social access and opportunity. If we cannot explain how our equity initiatives redistribute access and opportunity, we should reconsider them.

- The “Fix Injustice, Not Kids” Principle: Educational outcome disparities are not the result of deficiencies in marginalized communities’ cultures, mindsets, or grittiness, but rather of inequities. Equity initiatives focus, not on fixing marginalized people, but on fixing the conditions that marginalize people.

- The One Size Fits Few Principle: No individual identity group shares a single mindset, value system, learning style, or communication style. Identity-specific equity frameworks (like group- level “learning styles”) almost always are based on simplicity and stereotypes, not equity.

- The Evidence-Informed Equity Principle: Equity initiatives should be based on evidence for what works rather than trendiness. “Evidence” can mean quantitative research, but it can also mean the stories and experiences of marginalized people in your institution.

Ten Commitments for Equity-Literate Educators

The following commitments describe ten foundational orientations toward professional beliefs, self-development, and action that will help local leaders, educators, organizers, and facilitators become “equity literate” actors in their schools and communities:

- I will inform myself. I will find strategies for bolstering equity based on evidence of what works. I will look at this evidence in light of what I know about my own community. I will not limit “evidence” to quantitative data. I will seek the voices of local communities and stakeholders. I am not the expert of their experience.

- I will understand the “sociopolitical context” of schooling. I must be willing to see and understand the bigger context of societal and global inequity. Even if I don’t feel I have the power to end global poverty or systemic racism, these conditions have profound effects on students and families.

- I will work to see the conditions I’m conditioned not to see. The way privilege works, I’m least likely to recognize the inequities that privilege me. Learning to recognize them takes practice. I will practice.

- I will refuse the master’s paradigms. I will not minimize educational inequity to standardized test scores, refer to people as “at-risk,” describe somebody who has been “pushed out” as a “dropout,” or call something an achievement gap that is actually an opportunity gap.

- I will never reduce equity to cultural activities or celebrations. I will not settle for celebrating diversity or for “food, festivals, and fun.” Although they can be part of a bigger equity initiative, they do not make a school more equitable.

- I will not confuse equity with universal validation. Educational equity is not about valuing every perspective. An equity view does not value heteronormativity or male supremacy even when they are grounded religion. An equitable space—a school or university, for example—cannot be both equitable and hegemonic.

- I will resist simple solutions to complex problems. Simple solutions are tempting, but they distract me from finding serious solutions to complex problems. I will not buy into approaches that over-simplify complexities, regardless of how popular they are.

- I will work with and in service to marginalized communities. I will practice the ethic of working with rather than working on marginalized communities. I will apply my commitment to equity and social justice, not just in the content of my equity work, but also in my processes for doing that work.

- I will reject deficit ideology. I will refuse to identify the source of social problems by looking down rather than up power hierarchies. I reject the notion that people are marginalized due to their own “deficiencies.” I understand that educational outcome disparities have nothing to do with the grittiness, mindsets, or cultures of marginalized students. I commit to fixing injustice, not students.

- I will prioritize equity over peace. Although conflict resolution and mediation programs can be useful, they should not replace equity and justice efforts. Never, under any circumstance, should equity concerns be handled through processes that assume parties occupy similar spaces along the privilege-oppression continuum. In the end, peace without justice renders the privileged more privileged and the marginalized further marginalized; a condition that might be understood as the exact opposite of authentic equity.

Acknowledgments

Organizing Engagement thanks Paul Gorski for his contributions to improving this introduction and for permission to republish excerpts and images from his website and publications.

Creative Commons

This work by Organizing Engagement is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. When excerpting, adapting, or republishing content from this resource, users should cite the source texts and confirm that all quotations and excerpts are accurately presented.