Proposed by Elizabeth Rocha in the Journal of Planning Education and Research in 1997, the Ladder of Empowerment represents one of the first models that conceptualized individual and collective forms of empowerment. While earlier models described the dynamics of power or participation, Rocha’s Ladder addresses building power—i.e., the interrelationship of individual and collective participation and power—and the conditions that contribute to (or undermine) power building. Rocha’s Ladder of Empowerment follows several related models, including Sherry Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation and Roger Hart’s Ladder of Children’s Participation.

“At the heart of empowerment lie the needs of socially and economically marginalized populations and communities. As recent and ongoing economic restructuring and welfare state retrenchments continue, planners will increasingly be required to address the needs of such communities. Understanding empowerment, what it is, what it can and cannot do, and the variations within each type will enable planners to make informed decisions that will aid in achieving desired results and provide meaningful service to those who need it most.”

Elizabeth Rocha, A Ladder of Empowerment

Although Rocha’s primary audience is professional “public planners” such as local-government officials, the model is based on cross-disciplinary research and can be directly applied to issues in education organizing and engagement. For example, Rocha describes, in the context of public planning, a situation that is commonly encountered by district and school administrators:

“Questions arise challenging the legitimacy of professional knowledge, such as: Whose knowledge? What kind of knowledge? Or, as Baum describes it, conflicting and contested narratives…. Hoch states, ‘[e]fforts to emphasize professional status and expertise are an impediment to nurturing and expanding planning deliberations among citizens with different occupational, ethnic, racial, and religious affiliations.’ What he is referring to in this statement are citizens with knowledges and truths that diverge from those espoused by the planners.”

For Rocha, professional expertise and participant empowerment exist in an often precarious relationship. If professional expertise is used as a rationale for asserting unilateral power—for example, as a reason to exclude community members from a process that will directly affect them—professional expertise can become a justification for illegitimate forms of manipulation and disempowerment. Similarly, professionals, experts, administrators, and others in positions of authority may proceed on false assumptions because they assume their comparatively greater expertise gives them a more accurate view of the problem—and therefore its solutions. Rocha continues:

“These questions are also central to the practice of empowerment. Questions concerning the legitimacy of professional knowledge versus client knowledge are inextricably intertwined with the five empowerment types…. Solutions do not lie in an either/or dichotomy—ban professionals or fully privilege their knowledge—but somewhere in between. The potential lies in altering our understanding of the role of the professional. Viewing them…perhaps not as the arbiter of the only appropriate knowledge but as the arbiter of one (or several) types of knowledge while at the same time not privileging professional knowledge over the knowledge of others.”

In practice, authentic forms of empowerment must navigate “conflicting and contested narratives.” School administrators, for example, may believe that “empowerment,” in the context of learning, consists of raising test scores, eliminating the “achievement gap,” or teaching in ways that administrators believe will be most effective. Yet “empowerment,” for youth and families, may mean abandoning the quantitative, test-based measures that often drive school decision-making, hiring a more racially diverse faculty, or teaching in ways that are more culturally responsive and inclusive.

In other words, administrators may feel, for example, that empowerment should take the form of technical solutions (e.g., using instructional methods that are validated by research or taught in teacher-education programs), while students and families may feel that empowerment should take the form of adaptive solutions (e.g., listening to the needs, concerns, and priorities of students and families, and teaching in ways that reflect, value, and honor those perspectives).

For Rocha, the Ladder of Empowerment offers a framework that will help planners, administrators, public officials, and others holding positions of authority “to not only unpack empowerment, but also to unpack their own assumptions about who should be empowered, in what manner should they be empowered, and how a particular course of empowerment fits with particular structural conditions.”

The Ladder of Empowerment

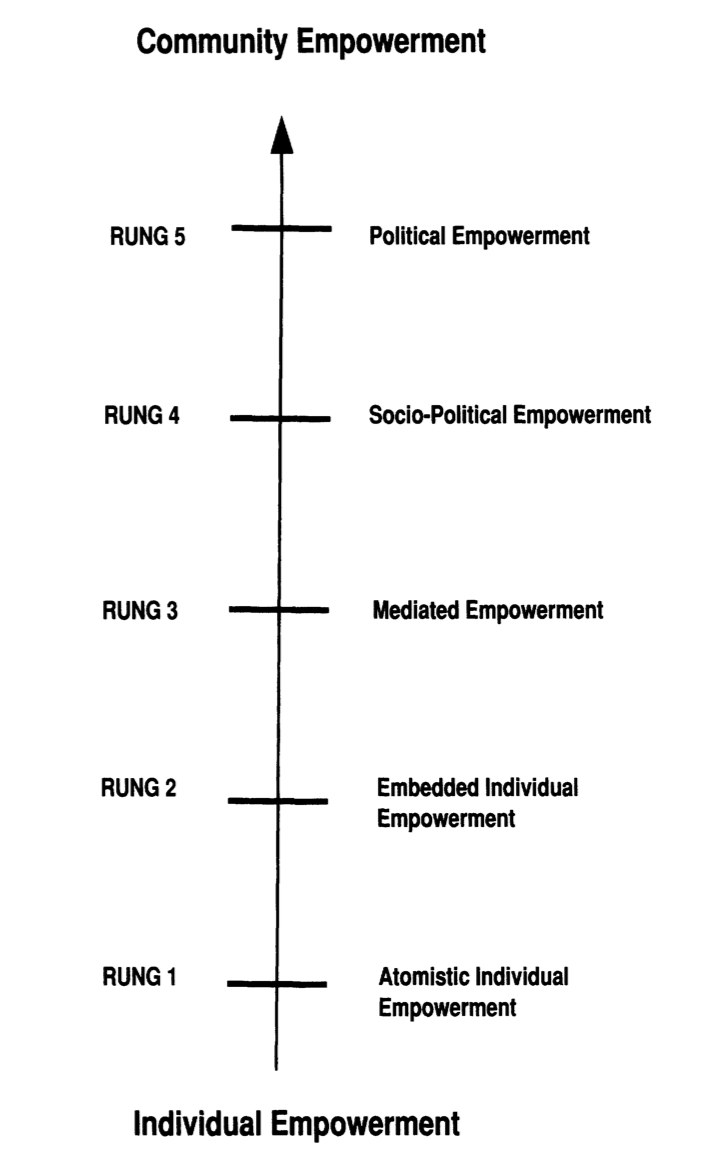

Elizabeth Rocha’s Ladder of Empowerment proposes a graduated progression, with the lower rungs reflecting less empowerment and the higher rungs more empowerment. The model also progresses from forms of individual empowerment (lower rungs) to community empowerment (higher rungs). The framework describes empowerment as a dynamic relationship between individual and collective agency: actions that are focused on individual empowerment represent the least amount of potential power in a community, while actions that bring about structural, political, and institutional changes throughout a system represent the greatest amount of potential power. As collective mobilization increases, so does potential empowerment, but ultimately legislative or legal mechanisms will be required to empower entire populations of people. It should be noted that while the Ladder of Empowerment has application in a statewide or national context, the model specifically describes empowerment relations in a community setting.

The five rungs of the Ladder of Empowerment are:

1. Atomistic Individual Empowerment

Type 1 empowerment refers to forms of empowerment that target individuals as “solitary units.” In Rocha’s words, “Atomistic individual empowerment is what might be termed a traditional understanding of empowerment: the locus is the individual; the goal is increased individual efficacy; and the process consists of altering the emotional or physical state of the individual. Atomistic individual empowerment is built on the rational actor model and explains the competence of one person. It is conceptually modeled after mental health treatment processes and refers to changing individual characteristics.”

Examples would include providing accommodations to people with disabilities so they can fully participate in a process, providing job training to the unemployed, or offering English-language instruction to immigrants. As Rocha notes, “This type of empowerment is most usefully applied to individual problems that do not require alterations in systems, social relations, or structural changes (over which the individual has no control) for its success. Critiques of this model likewise suggest that the application of this model of empowerment to social problems, such as homeless, may tend to perpetuate a blame-the-person subtext.”

2. Embedded Individual Empowerment

Type 2 empowerment refers to forms of empowerment that allow individuals to operate as effective actors in the context of larger groups, organizations, communities, or systems. Embedded individual empowerment consists of “the ability to understand one’s external context, to maneuver through it at a heightened level of facility with the goal of increasing personal efficacy and satisfaction.” Examples include pursuing higher education, postsecondary credentials, internship opportunities, or other forms of professional training or certification to improve one’s prospects for employability, career advancement, or income enhancement.

As Roche notes, however, “the critique of the embedded individual empowerment model is that it does not move the participant to treat the external environment as an element that can be acted upon [e.g., through political organizing or campaigns]; instead, external elements are simply understood in order to increase control over the self within existing structures and systems.” In short, embedded individual empowerment does not change the fundamental conditions of the system; it simply helps people better navigate and succeed in the existing system.

3. Mediated Empowerment

Type 3 empowerment refers to the mediating relationship that exists between experts and non-experts, for example, or between elected officials and voters in which the experts, officials, or other formal authorities either largely or entirely determine and control the available modes of empowerment. In Roche’s words, “Mediated empowerment is a highly professionalized model in which the process of empowerment is mediated by an expert or professional. The locus in this type can be either the individual or community, depending upon the specific circumstance. Its goals are to provide knowledge and information necessary for individual and community decision-making and action…. With guidance and expertise from the professional, the group gains the knowledge to participate in decision-making processes from an informed position.”

Usefully, Roche describes two fundamental forms of mediated empowerment: the prevention model and the rights model. In the prevention model, participants are “viewed essentially as children whose needs are prescribed by the expert, the parent.” In the rights model, participants are viewed as essentially “powerless” and lacking the necessary education, knowledge, or skills needed to fully participate in a process. While both forms are potentially paternalistic, the “crucial difference” between the two models, according to Roche, is that the rights model sees participants as having “the ability to exercise choice,” whereas the prevention model sees a participant as “a child to be looked after.” Although mediated empowerment can be empowering under the right conditions, each model may lead to disempowerment, especially when those in positions of power fail to question their assumptions, understand their own biases, or dismiss peremptorily the potential contributions of community participants.

4. Socio-Political Empowerment

Type 4 empowerment refers to individuals, groups, and organizations mobilizing to accumulate social and political power to challenge governmental or institutional authority. According to Roche, “Socio-political empowerment focuses on the process of change within a community locus in the context of collaborative struggle to alter social, political, or economic relations… Thus there are two levels of development occurring: The community is transforming itself from the inside into a powerful actor capable of garnering resources for local benefit; at the same time, members-of-the-community are transforming themselves from bystanders into actors.”

Examples include community-based organizations (CBOs) and community-development corporations (CDCs) that raise funding, develop programs, train community organizers, and undertake other actions to increase the political education and capacity of community leaders and residents.

5. Political Empowerment

Type 5 empowerment refers to political processes or policies that empower (or disempower) individuals and groups across an entire population, community, or system. As Roche notes, “The process of empowerment is political action directed toward institutional change… The focus is not on the process of change within the individual or group, but on the outcome.” Political empowerment occurs through electoral, legislative, or legal change, such as when laws are passed to protect groups from discrimination or when court decisions protect rights that have been infringed.

An illustrative example Roche discusses is legislation related to physical disability: “The powerlessness of the disabled community derives from attitudes buttressed by legal structures enforcing segregation and alienation. The goals of political empowerment efforts are legislative transformation that will alter the legal relationship between all community members and the environment. Although each disabled person would potentially benefit from such changes, the process of change does not include individual participation or transformation.”

Roche provides another useful example: “An important and ubiquitous form of political empowerment is the public consumption of specific cultural, national, or group symbols through public art, architecture, and, more broadly, the entire cultural landscape. Environmental designers and architects have the potential to contribute to community empowerment through the construction of environments in symbolic as well as strictly functional terms.” Political empowerment fundamentally alters a system—whether it’s through changes in policy or shifts in established convention—to empower individuals and groups that were formerly silenced, marginalized, oppressed, or otherwise disempowered by that system.

References

Rocha, E. M. (1997). A ladder of empowerment. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 17, 31–44.

Creative Commons

This work by Organizing Engagement is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. When excerpting, adapting, or republishing content from this resource, users should cite the source texts and confirm that all quotations and excerpts are accurately presented.