The Pathways to Participation model was developed by Harry Shier and first published in Children & Society in 2001. The model builds on Sherry Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation and Roger Hart’s Ladder of Children’s Participation. As Shier notes, “The new model owes a great debt to Hart’s work. It is not intended to be a replacement for the ladder of participation, but may serve as an additional tool for practitioners, helping them to explore different aspects of the participation process.”

“States Parties shall assure to the child who is capable of forming his or her own views the right to express those views freely in all matters affecting the child, the views of the child being given due weight in accordance with the age and maturity of the child.”

United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, Article 12.1

While Shier mentions that “many practitioners have found [the lower non-participatory levels] to be the most useful function” of Hart’s Ladder of Children’s Participation, because it helps them “recognise, and work to eliminate, these types of non-participation in their own practice,” Shier’s model excludes levels of false pseudo-participation in favor of a “pathway” that illustrates the methods adults can utilize to support a developmental progression of authentic child and youth participation. By eliminating the negative connotations typically associated with the lower rungs of ladder models, Shier’s approach offers a participatory progression that effectively functions as a scaffolding guide for educators and other adults working with children and youth.

Shier explains his rationale for developing the model:

“I hope that by presenting an ordered sequence of 15 questions, this model will serve as a usable tool for individuals, teams, and organisations working with children. In using the model, it is probably not helpful to see it as a point-scoring exercise, just ticking off as many boxes as possible. The most useful discussion will probably occur when the answer to a question is no. Then it can be asked, ‘Should we be able to answer yes?,’ ‘What do we need to do in order to answer yes?,’ ‘Can we make these changes?,’ and ‘Are we prepared for the consequences?’ Working with this model could thus be a useful first stage in developing an action plan to enhance children’s participation in all kinds of organisations working with children.”

As Shier notes, “It is unlikely that a worker (or an organisation) will be neatly positioned at a single point on the diagram. They may be at different stages at different levels. Also they may be at different positions in respect of different tasks or aspects of their work.” Shier therefore envisions the model being used as a tool for self-reflection and planning: “The model provides a simple question for each stage of each level. By answering the questions, the reader can determine their current position, and easily identify the next steps they can take to increase the level of participation.”

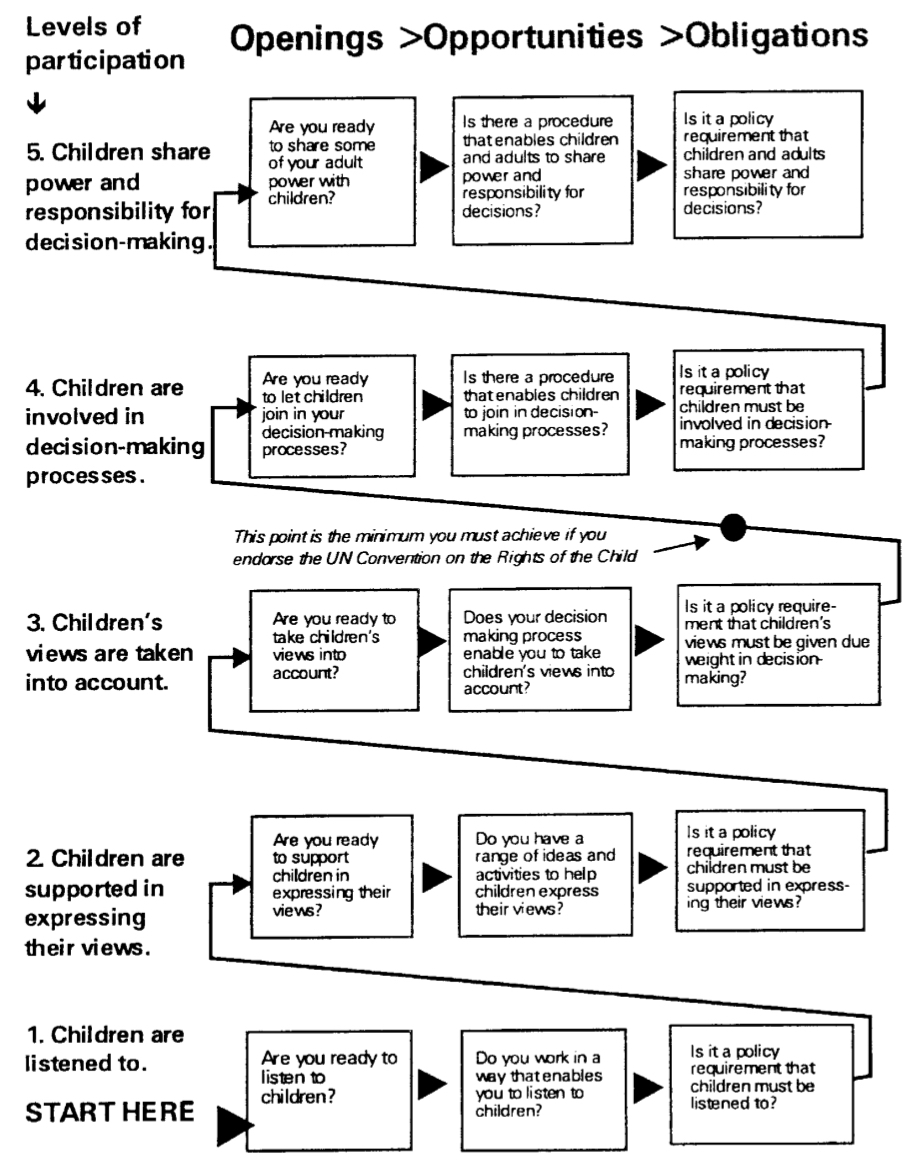

The original illustration of Harry Shier’s Pathways to Participation model as it appeared in Children & Society in 2001. Shier based the Pathways to Participation model on his experience working on child participation in the United Kingdom in the 1990s. He developed the model to align with Article 12.1 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which the United Kingdom ratified in 1991. Source: Pathways to participation: Openings, opportunities and obligations, Children & Society

The Pathways to Participation Model

Shier’s progressive “pathway” of child and youth participation encompasses five levels (presented vertically) and what Shier calls “three stages of commitment” (presented horizontally above the five levels).

The Five Levels

The five levels of the Pathways to Participation model:

1. Children Are Listened To

This level requires, according to Shier, “that when children take it upon themselves to express a view, this is listened to, with due care and attention, by the responsible adult(s).” At level one, “Listening occurs only in so far as children take it upon themselves to express a view. No organised efforts are made to ascertain what views they have on key decisions, and if no views are forthcoming, this is not seen as a cause for concern.”

2. Children Are Supported In Expressing Their Views

This level requires “children to be able to express their views openly and confidently” and “adults working with them must take positive action.” According to Shier, adults must actively and intentionally enable children and youth to overcome issues such as shyness, low self-esteem, negative self-beliefs, language barriers, cultural differences, or prejudice and stereotyping that may prevent them from expressing their opinions and ideas. While adults at level one may listen to children and youth, at level two they must create supporting physical and psychological conditions—such as environmental and emotional safety for the child, trusting relationships with adults, or an accepting school or community culture free from bias and discrimination, for example—that enable children and youth them to express their ideas and opinions.

3. Children’s Views Are Taken Into Account

This level requires that children’s ideas and opinions are not only heard, but also considered by adults and incorporated into their decision-making. Shier notes, however, that “taking children’s views into account in decision-making does not imply that every decision must be made in accordance with children’s wishes, or that adults are bound to implement whatever children ask for.” At this level, children and youth may be consulted through strategies such as youth surveys, student advisory committees, or curricular choices in a course.

4. Children Are Involved In Decision-Making Processes

This level requires that children and youth are involved in organizational governance and adult deliberations. At level four, children and youth are not only consulted, but they actively participate in decision-making processes with adults. Shier notes that involving children and youth in organizational decision-making can have a variety of benefits, such as “improving the quality of service provision, increasing children’s sense of ownership and belonging, increasing self-esteem, increasing empathy and responsibility, laying the groundwork for citizenship and democratic participation, and thus helping to safeguard and strengthen democracy.”

5. Children Share Power and Responsibility For Decision-Making

This level requires adults to not only involve children and youth in decision-making, but also to share power and responsibility for decisions. Shier provides a useful example that helps distinguish level five from level four: “At level four, children can be actively involved in a decision-making process, but without any real power over the decisions that are made. This occurs, for example, when young people are given a number of seats on an adult committee. If they are confident and articulate, they can put forward their views, and the adults will generally listen respectfully. However, they are clearly outnumbered, and the adults have an effective veto.” At level five, adults do not (as a matter of practice) or cannot (as a matter of policy) unilaterally overrule children and youth in a decision-making process.

The Three Stages of Commitment

The three stages of commitment in the Pathways to Participation model represent degrees of dedication and fidelity to the participatory empowerment of children and youth:

- Openings occur when adults and organizations become receptive to empowering children and youth, or when they recognize the potential utility of empowerment.

- Opportunities occur when adults and organizations have the funding, time, professional development, knowledge, skills, or other capacities required to empower children and youth in authentic and meaningful ways.

- Obligations when adults agree to codify child and youth empowerment in organizational policy or standard practice, and to hold themselves accountable by establishing expectations for adults and building requirements for child and youth empowerment into a system.

Acknowledgments

Organizing Engagement thanks Harry Shier for his contributions to improving this introduction.

References

Shier, H. (2001). Pathways to participation: Openings, opportunities and obligations. Children & Society, 15, 107–117.

EDITORIAL NOTE: Since the original publication of “Pathways to Participation” in 2001, Shier has twice revisited his model and extended his thinking about its features, applications, and implications:

Shier, H. (2006). Pathways to Participation revisited: Nicaragua perspective. Middle Schooling Review, 2, 14–19.

Shier, H. (2010). Pathways to Participation revisited: Learning from Nicaragua’s child coffee workers. In N. Thomas & B. Percy-Smith (Eds.),

Percy-Smith, B. & Thomas, N. (Eds). (2009). A Handbook of Children and Young People’s Participation: Perspectives from Theory and Practice (pp. 215–227). Abingdon: Routledge.

Creative Commons

This work by Organizing Engagement is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. When excerpting, adapting, or republishing content from this resource, users should cite the source texts and confirm that all quotations and excerpts are accurately presented.