Published in 2015 by the International Association for Public Participation (IAP2), the Quality Assurance Standard for Community and Stakeholder Engagement outlines a benchmark process for effective community and stakeholder engagement that includes brief descriptions of the essential practices, goals, features, and considerations for each step in the process.

The 11-step process and accompanying descriptions function as a “professional standards framework” designed to help professional practitioners and local leaders implement high-quality engagement processes and evaluate their effectiveness against a standardized model. The Quality Assurance Standard for Community and Stakeholder Engagement is intended to be used in conjunction with the organization’s Spectrum of Public Participation, Code of Ethics and Core Values for the Practice of Public.

“Governments and industry across the globe are increasingly recognising the value of community and stakeholder engagement as an essential part of significant project planning and decision-making. The paradigm of decision making consideration has shifted from a culture of ‘announce and defend,’ to one of ‘debate and decide.’ It is expected that engagement practices will identify, understand and respond to the interests, risks and interdependences of all project stakeholders as well as address legislative and public policy requirements for engagement.”

Quality Assurance Standard for Community and Stakeholder Engagement, International Association for Public Participation

In the introduction to the resource, the International Association for Public Participation explains its rationale for developing the standards framework and engagement process:

“The profession of community and stakeholder engagement has matured globally and reached the evolutionary point whereby it needs a professional standards framework to provide community, practitioner, and government confidence in the effective practice of engagement, as well as supporting career and professional pathways for practitioners in the field….

The operating environment for practitioners is now more complex than ever with stakeholders increasingly diverse and sophisticated in their views and expectations. Interdependencies and complexity amongst stakeholder groups can lead to the development of unpredictable relationships that have the potential to derail a project if their unique views and needs are not properly explored, understood, and addressed. A standardised process to formally assess the quality of an engagement practice which impacts on critical decision making and relationship outcomes is therefore paramount to the sustainability and future value of the discipline of community and stakeholder engagement.”

Process for Community and Stakeholder Engagement

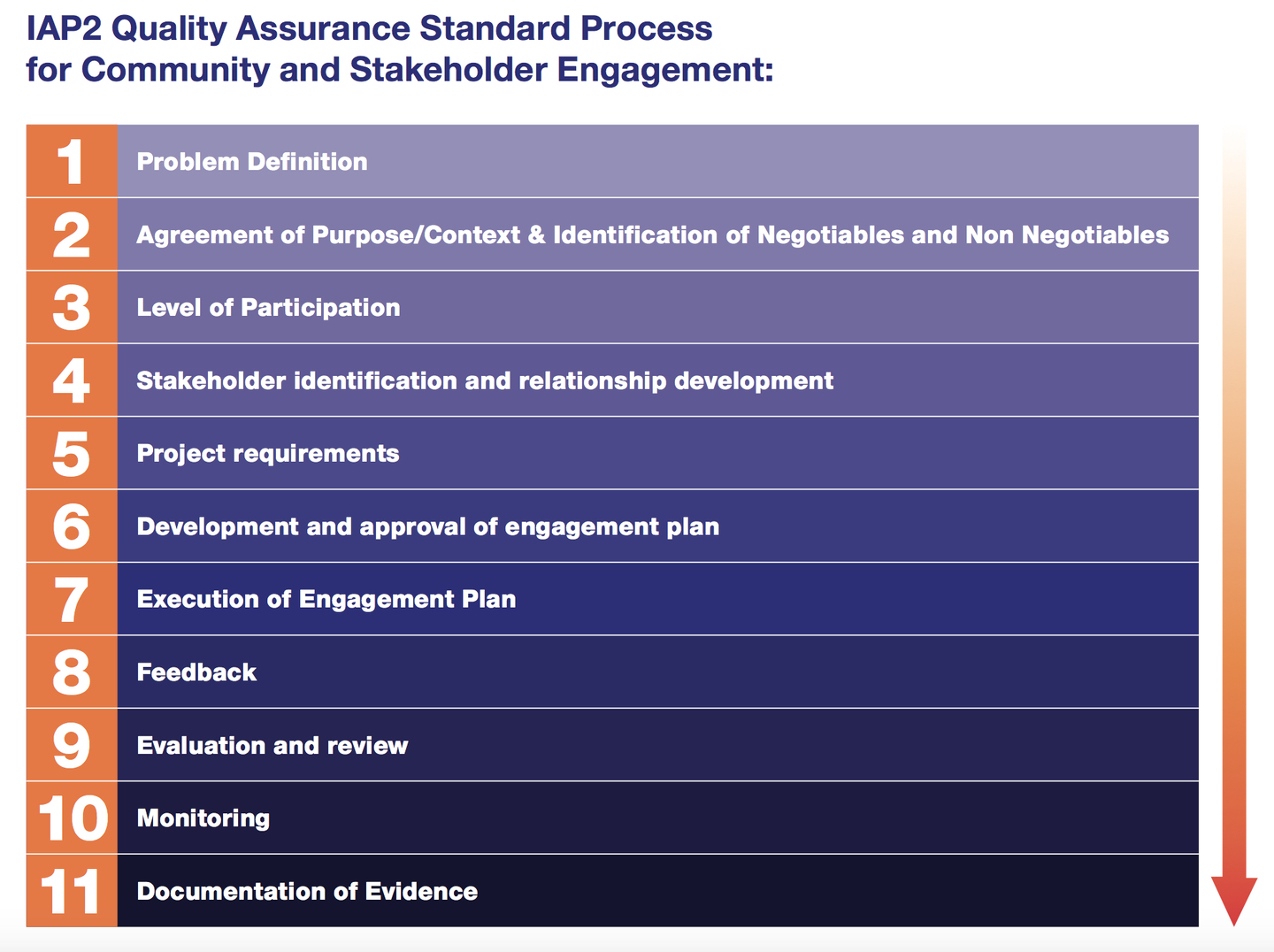

The International Association for Public Participation’s Quality Assurance Standard Process for Community and Stakeholder Engagement outlines 11 steps in a standard engagement process that can be applied in a wide variety of contexts and with diverse stakeholders and groups. The clarity and descriptiveness of the resource make it useful for both seasoned practitioners and those who are new to the field of community engagement and participation.

It should be noted, however, that the principal audience for the Quality Assurance Standard for Community and Stakeholder Engagement is engagement professionals such as organizers, facilitators, researchers, and evaluators, and therefore the process describes a number of practices that may not be applicable or feasible in certain contexts.

In many schools and communities, for example, local leaders do not have the time, funding, expertise, or other resources required to undertake a data collection and evaluation process as robust as the process described in the framework. In these cases, local leaders and organizers can adapt the process to suit their needs, context, or resource limitations, though they should remain mindful that the elimination of recommended steps and actions could compromise the effectiveness or impact of the engagement process.

The eleven steps in the Quality Assurance Standard Process for Community and Stakeholder Engagement:

1. Problem Definition

The first step in the engagement process is problem identification and definition: What problem will the process attempt to solve or mitigate? Who is being affected by the problem or will be affected by its resolution? What is the desired outcome of the process? Who will determine whether the process has worked? Ideally, local leaders, organizers, and facilitators should develop a “problem statement” that articulates both the objectives of and rationale for the process.

2. Agreement of Purpose/Context and Identification of Negotiables and Non-Negotiables

The second step is vital to the success of the engagement process. At this stage, local leaders, organizers, and facilitators—in collaboration with stakeholders—should develop a “context statement,” or a declaration of collective agreement describing the purpose of the process, and they should identify negotiables and non-negotiables. The framework lists 14 elements of a comprehensive context statement, including specify the decisions that need to be made; consider the existing culture, values, and attitude towards engagement; map out project and organisational interdependencies; and identify risks.

At this stage, it is also vital that local leaders and organizers clearly name and communicate what is either on or off the table in terms of stakeholder involvement, decision-making, and authority: “In most projects there are likely to be elements that cannot be influenced by stakeholders. This may be due to budget, viability, safety, or legislative requirements. These elements are the ‘non-negotiables’ and need to be clearly communicated to stakeholders at the commencement of the engagement exercise. Engagement practitioners are responsible for clarifying the opportunity for community change and input and therefore focussing stakeholder attention on the ‘negotiables’ or projects aspects that they can influence.”

Engagement processes often go awry when stakeholders hold or develop expectations that fall well outside the scope of process. When local leaders fail to establish appropriate expectations by naming the negotiables and non-negotiables, it significantly increases the odds that process will become confusing or frustrating to participants and stakeholders, which can lead to contention rather than collaboration.

3. Level of Participation

The third step in the engagement process is determining the appropriate mode (or modes) of community and stakeholder participation. To help local leaders, organizers, and facilitators determine the most suitable level of participation for a given process or project, the resource recommends using the Public Participation Spectrum as a guide. The Public Participation Spectrum describes five general modes of public participation—informing, consulting, involving, collaborating, and empowering—that fall on a progressive spectrum of increasing influence over decision-making in a given engagement context. The spectrum will “enable an assessment of the extent to which the project meets public expectations or promises…it also helps stakeholders to understand the basis on which decisions are made and the reasons why particular actions are required.”

4. Stakeholder Identification and Relationship Development

The fourth step in the engagement process is the identification and recruitment of stakeholders, which is defined as “any individual, group of individuals, organisation, or politics entity with an interest or stake in the outcome of a decision.” Local leaders, organizers, and facilitators should ask: Who is being affected by the problem or will be affected by the outcome? Which voices need to be included? Which groups have been historically marginalized in the community? The framework recommends a systematic process of stakeholder identification to ensure that important voices and groups are not left out, and it provides basic guidance on how such an analysis should be conducted.

Relationship development at this stage is also paramount: “Practitioners should also ensure they recognise potential impediments to engagement participation of any party affected, involved, or requiring a voice as a part of the exercise…. This will include identifying the expectations of stakeholder groups and contemplating these against the project objectives to detect possible conflict areas or a misalignment in participation expectations.” In short, relationship-building requires local leaders and organizers to develop a deep understanding of the community and stakeholders—their needs, expectations, priorities, frustrations, etc.—since it will “heavily influence the communication and engagement techniques to be employed.”

In addition, a relationship-building process is also a trust-building process, and trusting relationships between leaders and stakeholder are often decisive factors when it comes to not only the success and efficacy of the engagement process, but also the levels of receptivity, support, buy-in, endorsement, and enthusiasm for the process and its outcomes among participants and within the broader community.

5. Project Requirements

The fifth step in the engagement process is the identification and articulation of the project’s requirements—what needs to happen and when. While many potential engagement activities or strategies will be optional, others may be required due to specific local needs, expectations, circumstances, or resource limitations. At this stage, it is important to map out and document all requirements, particularly non-negotiable requirements. For example, the engagement process may be funded by a grant that entails specified deadlines, expectations, and budgetary parameters, or the process may culminate in an election, vote, or decision scheduled for a particular date.

The framework provides several examples of common requirements in an engagement process, such as timeline parameters and deliverable deadlines, budgetary and staffing constraints, legislative and policy-related stipulations, essential training and specialized expertise, or reporting and evaluation requirements.

6. Development and Approval of Engagement Plan

The sixth step in the engagement process is the collective development and endorsement of an action plan. The process for developing an action plan can take many forms, and the process is typically determined by specific local needs, objectives, concerns, or contextual constraints. In some cases, for example, a smaller representative group of stakeholders will develop a plan comparatively quickly and then seek broader approval from the community, while other planning processes will involve a much larger group of stakeholders and will require a lot more logistical coordination and funding, a dedicated staff or group of volunteers, and multiple months to execute.

The framework lists several elements of an effective engagement plan, including features such as a purpose statement, schedule of activities, itemized budget, descriptions of roles and responsibilities, and strategies for recruitment, communication, and risk management.

7. Execution of Engagement Plan

The seventh step in the engagement process is the execution of the completed plan. Specific implementation needs will be articulated in the collaboratively developed and approved plan, but the framework lists seven common features of successful execution, such as raising and securing all the resources necessary for implementation, maintaining fidelity to the agreed-upon timeline, ongoing relationship-building and communication with participating stakeholders, compliance with legal and legislative requirements, and process evaluation and reporting.

8. Feedback

The eighth step is soliciting and collecting feedback on the engagement process from participants and other community stakeholders. A feedback process is typically less formal than an evaluation, but it is generally just as important because it provides opportunities for local leaders and organizers to hear multiple perspectives directly from stakeholders, learn about what worked and didn’t work without having to wait for the findings of a formal evaluation, and demonstrate to participants that the local leaders and organizers are receptive to critical feedback and willing to act on community recommendations.

The framework identifies three fundamental features of effective feedback processes: a statement of feedback is promised to all participants as a part of the engagement process; processes are identified for feeding back the results to the stakeholder; and feedback is collated and made available to all stakeholders.

9. Evaluation and Review

The ninth step is the review and evaluation of the engagement process, a stage that is often executed in partnership with independent professional evaluators. In some cases, the evaluation will be conducted due to formal requirements (e.g., because it is part of a federal, state, or private grant program), while in others local leaders and organizers will electively conduct an evaluation to better understand why a process worked or failed, or to collect data and other evidence they can use to make a stronger case for investing in continued engagement work in the future.

The framework describes several features of effective evaluations, including the extent to which engagement objectives were achieved, the degree to which stakeholders were involved or empowered, and the measurable impact the process had on stakeholders or the community.

10. Monitoring

The tenth step in the engagement process is the monitoring of any ongoing implementation and its effects, as well as longer-term, post-evaluation performance assessment. Monitoring provides local leaders and organizers with opportunities to gain deeper insights into the impact of engagement work (perhaps as part of a continual improvement process) or to ensure accountability to the agreements and decisions made during the engagement process.

Importantly, the framework notes that “monitoring should influence decision making on how improvements can be made and organisational culture enhanced to ensure appropriate engagement is embedded into routine activities.” In other words, ongoing monitoring increases the likelihood that effective engagement practices will be embedded in the governance, culture, and operation of local agencies, organizations, and community partnerships.

11. Documentation of Evidence

The final step in the engagement process is the documentation of evidence, which often includes the presentation, publication, and dissemination of lessons, data, and results. This documentation can include everything from process documentation (e.g., discussion guides, statements, the action plan, etc.) to feedback data (e.g., survey results, stakeholder statements, etc.) to evaluation and monitoring reports. Documentation of the actions undertaken and the outcomes achieved can “provide an internal mechanism for continuous improvement.”

To this end, the Quality Assurance Standard for Community and Stakeholder Engagement includes a detailed overview of an audit process—with an accompanying chart aligned with the International Association for Public Participation’s core values—that local leaders and organizers can use to inform their documentation and reporting process.

Acknowledgments

Organizing Engagement thanks Ellen Ernst for her contributions to improving this introduction, and the International Association for Public Participation for permission to reproduce excerpts and images from its publications.

References

International Association for Public Participation Australasia. (2015). Quality Assurance Standard for Community and Stakeholder Engagement. Victoria, Australia: Author.

Creative Commons

This work by Organizing Engagement is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. When excerpting, adapting, or republishing content from this resource, users should cite the source texts and confirm that all quotations and excerpts are accurately presented.