Zack Mezera

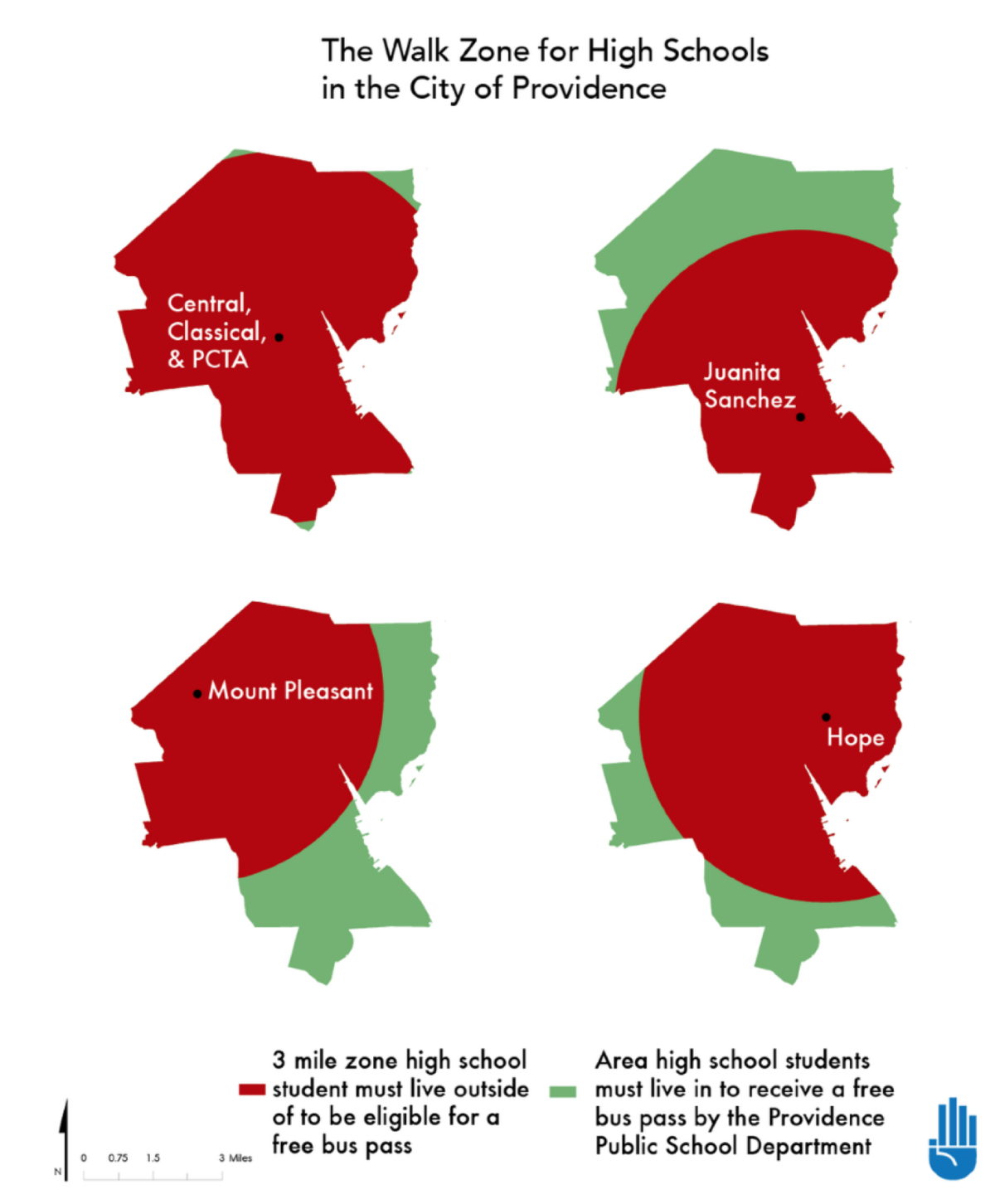

Zack Mezera is the outgoing executive director of Providence Student Union, a youth-led nonprofit organization in Rhode Island that helps students develop leadership and self-advocacy skills, organize to demand more equitable schools, and build power to win a fair say in their education systems. Since 2010, Providence Student Union’s youth leaders have waged several successful organizing campaigns, including campaigns to expand free school transportation, introduce ethnic studies courses, and secure funding for dilapidated school facilities. Providence Student Union also led a multiyear fight against a state-mandated high school exit exam—a campaign that compelled state leaders in 2014 to place a three-year moratorium on the testing policy. Mezera has also served on the Providence Ethics Commission and advised and led local electoral campaigns.

Interview by Stephen Abbott

Q: Let’s dive right in. You’ve spoken out about the lip service that is often given to youth leadership, and how some adults will claim they support youth voice even when they don’t let youth make decisions of any consequence. What problems have you seen result from inauthentic approaches to youth leadership?

To be clear: I believe almost everyone who makes a deep commitment to work on youth leadership has good intentions. Being an educator or youth-service provider can be as spiritually draining as it is fulfilling, and I don’t believe anyone persists in this field unless they truly believe they are doing the best they can for young people.

That said, latent adultism—the systems designed to oppress young people, and how those systems manifest in or through individuals and organizations—can distort those good intentions and lead to negative outcomes for youth. Over time, inauthentic forms of youth leadership inevitably reveal themselves, and in the worst-case scenarios students may drop out of civic engagement, perhaps for good.

Traditional student government is a good example. I’ve seen students who have been enthusiastic participants in student government, which tends to be focused on things like planning dances, but many of those students realized after graduation that none of the problems at their school have been improved for future generations. They may have built up their resume, but they didn’t acquire the knowledge or skills that will help them build or influence power as adults.

Inauthentic forms of youth leadership can also leave students demoralized about the efficacy of government or civic institutions in general, which is not only a real shame, but it’s the opposite of what many adults hope public schooling will instill in youth. In these circumstances, who fell short? Was it the 17-year-old student who had never been in a leadership role before? Or was it the school system itself, which didn’t entrust the student with the training, culture, and decision-making power the student needed to feel like a meaningful participant in their own education or community?

I also think we often set a bar for youth leadership that is far too low, which is ironic considering that our national education debate has been so heavily focused on “high expectations” for so many years. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen Providence Student Union members testify on legislation at the Rhode Island State House and receive applause from elected officials afterward—no matter what they said in their testimony or whether they said it well. Yet I’ve never seen anyone clap when adults testify. It’s apparent that the applause reflects the low expectations that some of those legislators, and adults in our society more generally, have for students, and particularly for students of color. I also believe a similar patronizing mentality can be present in many programs designed to serve youth, causing unseen damage generation after generation.

Q: Another thing we’ve talked about in the past is that, in some schools, youth-leadership programs are viewed as optional or recreational activities that adults can arbitrarily start or end, often without even consulting the students involved. Make the case for genuine youth-leadership programs: Why are they essential? And why should they always be developed in consultation and collaboration with youth?

One only has to look at our polarized national discourse and political environment to see the importance of genuine youth-leadership programs. Unfortunately, our education system has put civic education on the back burner for decades. If we take our current situation and fast forward 20 or 30 years, and our youth—who are now voting-age adults making all kinds of contributions to our society—are still civically underprepared, or they believe that politics is an inevitably shallow and ineffective exercise, then what have we accomplished?

Again, I want to reiterate that these challenges in youth-leadership programs are not the result of malice. Many of these programs suffer simply because they’re facilitated by a single teacher who is struggling to balance a heavy workload. Many others are funded only by donations or fundraising, meaning that minimal financial support is coming from the system itself, which then pushes young people into running bake sales instead of learning about power or practicing decision-making in more impactful ways. Ultimately, these pseudo-leadership programs are ineffectual, or they fall apart, or students lose faith and stop participating, which then contributes to the general feeling among many young people that authority figures do not have their best interests at heart.

But there is another way to do youth leadership, and it usually starts with asking young people what they like about their school and what they want to change. Adults can help create a safe and empowering structure for real youth decision-making, and they can invest in the long-term viability of the programs by providing funding for workshops, materials, transportation, and dedicated adult mentors who can facilitate the programs part-time or full-time. If we want a local and national politics that is brave enough to address root causes, that is transparent and accountable, and that prioritizes the people at the bottom of the socioeconomic spectrum or the groups that have been marginalized or oppressed for generations, I strongly believe the foundation for that kind of politics must begin with an investment in authentic youth leadership in schools.

Q: One of Providence Student Union’s driving philosophies is that’s it’s okay to let youth make mistakes, particularly if those mistakes are made in a safe environment in which youth have adult guidance and mentorship. What are the benefits of allowing youth to make mistakes, and what consequences have you seen result from overprotective approaches to youth development?

This question gives me an opportunity to talk about what groups like Providence Student Union mean when we say “youth leadership” or “youth-led.” At PSU, youth leadership means supporting youth to make substantive decisions about their lives, schools, and communities. Operationally, it means that youth choose and design our campaigns, they lead and scaffold our actions, and they participate in nearly all our major organizational decisions and even hire our staff. At PSU, we do our best to avoid simply maneuvering youth into testifying at hearings, being the token youth face on a committee, or chasing grant funding and donations.

Because our youth members have real responsibilities with real-world consequences, they sometimes make what might be considered strategic organizing mistakes—or, rather, they do things that adults might see as “mistakes,” but that we see as opportunities for learning and personal growth. Maybe they’ll want to start a petition when they could have held a meeting first, for example, or maybe they accept no for an answer when they could have pushed harder. But no matter what, the youth working with PSU take actions because they believe them to be the best next step to achieve their collective goals.

The stakes for individual students in authentically youth-led programming are real. In an environment where adults have veto authority over everything, youth will only learn a particular kind of leadership—the kind that those adults find acceptable or palatable. This typically means that protests, demonstrations, walkouts, or anything that’s disruptive in any way is off the table. It’s a shame because this adult-sanctioned approach to youth-leadership programming restricts young people’s engagement and creativity and skill development when it comes to engaging in the public sphere over the long-term.

“These actions may look ridiculous to some, or they may be seen as disruptive or antagonizing to others, but the fact that they were conceived and led by youth gave them a moral authority that helped focus attention on the issues that students—not adults—wanted to see addressed. And if certain actions don’t happen to succeed, the experience is always a learning opportunity. We may not win the issue, but our youth members pretty much always come out feeling more confident and capable than they were before.”

Look, today’s problems are enormous, and solving them will require the kinds of creative, unconventional engagement that often comes from young people. It was our embrace of this mindset that led Providence Student Union to give prominent adults in our community a mock version of our state’s standardized test or to dress up like guinea pigs during a demonstration at our State House. These actions may look ridiculous to some, or they may be seen as disruptive or antagonizing to others, but the fact that they were conceived and led by youth gave them a moral authority that helped focus attention on the issues that students—not adults—wanted to see addressed. And if certain actions don’t happen to succeed, the experience is always a learning opportunity. We may not win the issue, but our youth members pretty much always come out feeling more confident and capable than they were before.

Youth-led programs like PSU believe that youth have the power to lead and change their communities, and our programming allows them to harness their power to pursue goals they believe are important. But this commitment to youth-led organizing doesn’t necessarily require rallies, petitions, and walkouts. Every high school can give students control over writing the school dress code, for example, and every school should involve students in writing up the code of conduct and discipline policies. Schools can use youth-led participatory budgeting to determine, let’s say, how to spend technology funds. Or teachers can let students debate about and choose the books they read each year in English class or the questions they want to explore in a science course. Every facet of schooling can be an opportunity for genuine youth leadership.

Q: As you just mentioned, Providence Student Union often engages in high-profile actions—such as protests, demonstrations, or school walkouts—that directly challenge the prevailing power structure in schools. You just touched on this as well, but why did your youth leaders believe some of these visible public actions were necessary? And what are some of the advantages and disadvantages of youth engaging in more confrontational approaches to educational justice?

Although Providence Student Union has a reputation for being confrontational, that’s far from the whole story. For every sit-in we might hold at a decision-maker’s office, we do a hundred meetings with school staff, testimonies at hearings, student surveys, youth trainings, op-eds, or video testimonials, to name just a few things. The interesting thing to me is seeing the huge range of ideas that young people come up with, and Providence Student Union doesn’t attempt to pump the brakes on any of these approaches to advocacy. I’d argue that the softer power of building relationships with partners and decision-makers is just as important in PSU’s work, even though it doesn’t get the same level of media attention.

It’s important that decision-makers trust that we’re playing fair and that we’re actually trying to solve real problems—not just coming after them. But, yes, when you largely avoid imposing boundaries on student advocacy, you also create the possibility of direct actions that focus media attention and public pressure on decision-makers. We may go to meetings and help write legislation, but if the final legislation isn’t what was promised, we believe that work is only effective if it’s followed up by a protest outside their office.

“Society pretty severely limits the types of power young people have: they can’t vote, they can’t serve on juries, they have limited economic power, and they even have low levels of autonomy over their own bodies—students in our schools have to ask to use the bathroom, for example. But what they do have is the power that comes from subverting those low expectations, such as the belief that youth are ‘apathetic’ or ‘entitled.’ PSU’s more confrontational actions and creative stunts play with these narratives about youth engagement and agency, and they focus the attention of people with traditional forms of power—votes, time, influence, money—on the issues that really matter to students.”

These kinds of actions are important for so many reasons. For one, society pretty severely limits the types of power young people have: they can’t vote, they can’t serve on juries, they have limited economic power, and they even have low levels of autonomy over their own bodies—students in our schools have to ask to use the bathroom, for example. But what they do have is the power that comes from subverting those low expectations that I talked about earlier, such as the belief that youth are “apathetic” or “entitled.” So PSU’s more confrontational actions and creative stunts play with these narratives about youth engagement and agency, and they focus the attention of people with traditional forms of power—votes, time, influence, money—on the issues that really matter to students.

At the same time,

we always have to approach student-advocacy work as a ground on which learning

can begin. We aren’t so naive to believe that young people are fully actualized

political actors. After all, who truly is? Students may gravitate toward the

classic, higher-profile actions such as rallies or walkouts because that’s what

they’ve seen in the media. We all have an image of what a “protest” looks like

in our mind. PSU’s work is to help students make those images a reality in some

cases, but it’s also about encouraging them to expand their understanding of

what civic engagement can or should be. In the right circumstances, a video

testimonial can be as effective as a sit-in. But it’s up to our students to

make that decision, of course—and that’s how it should be.

Q: I want to stay on this theme a little longer. Regardless of whether students have or haven’t protested a school policy or decision, many school administrators adopt a defensive posture toward youth organizing in general, perhaps because they feel their authority may be threatened or undermined if they allow certain activities to happen. Let’s say administers sanction a student-organizing activity, and then that activity gets unruly or precipitates a media firestorm or puts pressure on the district to back away from some policy, then those administers could draw fire for approving the activity or could be called out for hypocrisy if they attempt to shut it down or silence students. Maybe the rationale, then, is that’s it’s just safer and easier to keep students quiet and contained. Why do you believe school leaders should support youth organizing even if it sometimes results in disruptive actions that challenge their authority?

Let me start with an analogy: a lot of people are members of the American Civil Liberties Union, even though they may not agree with 100% of the stances the ACLU takes. That’s because these members believe in the principles that the organization stands for, and they believe that fidelity to those principles will result in a better world. I think the same principled stance should be applied to youth organizing in schools.

Sure, sometimes students will challenge your positions. But students advocating for their interests and their rights is also going to improve the school in the long run, so I think administrators and teachers should get behind it. We see this dynamic play out all the time at PSU—faculty may be frustrated this month that we’re challenging their bathroom policies, but they also know that PSU helped win millions of dollars in school-transportation funding last year, so ultimately it’s in their interests to treat us as a partner because they directly benefit. And, of course, school leaders also appreciate that these student activists generally become more engaged in their education.

“Student advocates are trying to fix what they’re experiencing in their environment. You may disagree with their analysis, but it’s at least bringing to the surface a real issue the students are experiencing. Not investing in or suppressing youth voice and organizing leaves these perspectives and data points unsurfaced, which then gives teachers, administrators, or politicians less information to make wise decisions. If you want to run a student-centered school, you need to know what works or doesn’t for students—it’s that simple.”

When administrators are nervous about supporting or facilitating genuine youth leadership, I typically give them three reasons why I think they should get on board.

First, I tell them to remember that student advocates are trying to fix what they’re experiencing in their environment. You may disagree with their analysis, but it’s at least bringing to the surface a real issue the students are experiencing. Not investing in or suppressing youth voice and organizing leaves these perspectives and data points unsurfaced, which then gives teachers, administrators, or politicians less information to make wise decisions. If you want to run a student-centered school, you need to know what works or doesn’t for students—it’s that simple.

Another thing is that adults should consider what’s at stake for students when they get punished for taking bold stances. Young people are at the whim of adults in so many ways: if the young people involved in student government decide to pass around a petition that takes a stance against an administrative decision, in many schools those students can get detention, have their grades reduced, can lose recommendations, be removed from student-government positions, or get kicked off sports teams and clubs. These kinds of punishments can have lifelong repercussions: students may become academically disengaged and not reach their potential, they may come to resent and distrust authority, or they may not get into the college they want.

“The law requires youth to attend school, and yet countless thousands of students are putting their heads down in class, ‘acting up,’ leaving school, or not showing up at all. I would encourage all of us who work with young people to see these behaviors not as problems to be solved, but as individual acts of resistance on the part of those disaffected and disengaged students. In other words, student resistance is happening all the time in schools, even when it doesn’t take the form of a protest or walkout—students are resisting by dropping out and tuning out.”

If a student walks out of school and gets a suspension, they not only miss learning time, but they may also miss a meal the next day or they may not return to school at all. And if they are not in school, they are more likely to be captured by the criminal justice system. Sadly, we also know that those kinds of punishments are more frequent and more severe for students of color, LGBTQ students, immigrants, and students with disabilities—the students who are most likely to already be marginalized and who need the most support. So administrators should recognize that young people are often weighing the risks of their actions. Under these restrictive conditions, student action should be celebrated as an act of courage, not seen as something that needs to be suppressed. While there’s no need to worry about a student walkout happening every day, there is a very real need to worry about the harmful, snowballing effects of suppressing and punishing student voice.

Finally, we also need to keep in mind that students are, in fact, “walking out” every day in their own way. The law requires youth to attend school, and yet countless thousands of students are putting their heads down in class, “acting up,” leaving school, or not showing up at all. I would encourage all of us who work with young people to see these behaviors not as problems to be solved, but as individual acts of resistance on the part of those disaffected and disengaged students. In other words, student resistance is happening all the time in schools, even when it doesn’t take the form of a protest or walkout—students are resisting by dropping out and tuning out.

There will always be pushback in every system, and youth happen to be particularly good at it. So it’s up to the school leaders whether they will continue to support the status quo—especially when it’s failing or harming students—or whether they will nurture that resistance in productive, growth-oriented directions that not only improve schools, but that also give generations of young people opportunities to practice the substantive work of being an active, engaged citizen.

Q: One final question before we wrap up. You’ve been with Providence Student Union for ten years, but you recently announced that you’ll soon be moving on from your role as executive director. Do you have any final thoughts or reflections you want to share?

Thank you. I’ll just say that it’s meant so

much that I had the opportunity to be part of a local and national community

defending youth rights and advancing structural education reform from the

ground up.

A few thoughts come to mind.

With all that’s going on in our country today,

it’s easy to forget that fostering deep relationships is the key to improving

our communities and our world. Take the time it takes to develop those

relationships—make it a priority.

I will also say that organizers, in particular,

need to remember to go where the people actually are, which means the movement should

expand beyond school buildings as the only sites of the struggle.

“If we want to change our systems, youth organizing represents the highest dollar-for-dollar return on investment that I’ve seen anywhere in education.”

To funders: Don’t overlook, underfund, or undervalue youth organizing. I’ve seen universities and research outfits receive hundreds of thousands, or even millions, of dollars in funding to conduct evaluations and produce reports, while youth-organizing groups around the country are perpetually scrambling to raise budgets that are orders of magnitude smaller. I am a big fan of current conversations happening within foundations about “decolonizing wealth” in the funding world, and these funders truly need to make equity, and unconventional investments like organizing, their default funding priorities. If we want to change our systems, youth organizing represents, in my experience, the highest dollar-for-dollar return on investment that I’ve seen anywhere in education.

And to everyone who continues to fight for a just education system every day—whether it’s teachers, staff, parents, or advocates—keep it up. Don’t stop even if it sometimes feels like thankless work. We have a young generation that is, in many ways, coming to the rescue. If we can truly empower these young people, I believe that we will be able to build an education system that respects and honors the dignity of every student and family—and it can happen sooner than many people realize.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Copyright

Copyright © by Organizing Engagement and Zack Mezera. All rights reserved. This interview may not be reproduced without the express written permission of the publisher. Brief quotations are allowed under Section 107 of the Copyright Act.