Participatory budgeting is a democratic civic-engagement process that allows community members to decide how to spend portions of an annual public budget. The first participatory-budgeting process took place in the Brazilian city of Porto Alegre in 1989 as a strategy for helping the community root out corruption and address economic inequality. In the decades since, participatory budgeting has been used in thousands of communities and institutions around the world, and it has involved hundreds of thousands of community members in determining how public funds are spent in municipalities, governmental agencies, universities, districts, schools, and other public institutions and programs.

“From September 2013 to April 2014, more than 18,000 New Yorkers

A People’s Budget: A Research and Evaluation Report on Participatory Budgeting in New York City, Community Development Project at the Urban Justice Center in collaboration with the PBNYC Research Team

in ten City Council districts came together for the third cycle of Participatory Budgeting in New York City. Through this community-driven budgeting process, they brainstormed ideas to improve their neighborhoods, volunteered to refine those ideas into project proposals for the district ballots, and, ultimately, came together to vote on which proposals should be funded. These New Yorkers exercised direct decision-making power to allocate over $14 million of City Council funds: an increase of nearly $9 million from the first cycle of Participatory Budgeting in New York…. As in previous years, this cycle of Participatory Budgeting engaged those who are often disenfranchised and excluded from traditional voting and other forms of political participation. Young people, people of color, low-income earners, immigrants, women, and formerly incarcerated people are encouraged to participate in PB, and work with others in their district, as well as their elected officials, to generate ideas, craft proposals, and make real, lasting decisions about their communities.”

In the United States and Canada, the Participatory Budgeting Project is the principal nonprofit organization supporting local officials, leaders, organizers, and facilitators to create and implement participatory-budgeting processes designed to strengthen local democracy and make public budgets more equitable and effective. Participatory Budgeting Project has worked with numerous local partners to engage residents in spending hundreds of millions of dollars on thousands of community projects.

Read the Organizing Engagement interview with Shari Davis, 2019 Obama Foundation fellow and co-executive director of the Participatory Budgeting Project →

According to the Participatory Budgeting Project and independent evaluations, the potential benefits of participatory budgeting include:

- Creating opportunities for participating community members to offer diverse perspectives, innovative ideas, and useful feedback to public officials, elected representatives, or school administrators—including insights and information they would not have had otherwise—which can help local governments and institutions become more effective and responsive to community concerns while also producing more innovative solutions to public problems and better results for stakeholders and residents.

- Allowing community members to learn, deliberate, and create solutions collaboratively, which can help residents develop stronger empathy for one another or appreciation of cultural differences, while also helping community members better understand the complex challenges and limitations faced by people working in government.

- Improving the motivation of public officials, elected representatives, or school administrators to listen and respond to community concerns and ideas, which can then improve government accountability to the people it serves.

- Facilitating direct and active participation in a public decision-making process that delivers tangible results, which can help to reduce the apathy, distrust, or frustration that characterize many government-community relationships, while also increasing faith in and support for public officials and institutions.

- Increasing community participation in democratic decision-making, voting, and volunteerism, which can also help to cultivate future leaders and policymakers by motivating youth and residents to contribute their energy, talents, and passion to public service.

- Providing historically disenfranchised populations—such as youth, low-income populations, people of color, or undocumented residents—with opportunities to be meaningfully involved in local policy-making, while also helping to increase equity and justice within public systems and institutions.

Participatory Budgeting in Schools

The Participatory Budgeting Project created a detailed step-by-step guide to implementing participatory budgeting in schools and classrooms. The guide describes different ways that participatory budgeting can be used in educational and instructional settings, and it features details planning guidance, lesson plans, and worksheets that can be used by administrators, teachers, youth organizers, and student leaders. The guide also describes some of the benefits for schools communities and students:

For school communities:

- It’s democracy in action.

- It gives your students a positive civic-engagement experience.

- It serves as a bridge for your students to be engaged in politics and their community.

- It strengthens the school community by building positive relations between students and the administration.

- It shows students the benefits of getting involved.

Students will:

- Increase their ability to work collaboratively.

- Develop research, interviewing, and surveying skills.

- Develop problem-solving and critical-thinking skills.

- Develop public-presentation skills.

- Increase their awareness of community needs and their role in addressing those needs.

- Understand budgetary processes and develop basic budgeting skills.

- Identify ways to participate in governance.

- Increase their concern for the welfare of others and develop a sense of social responsibility.

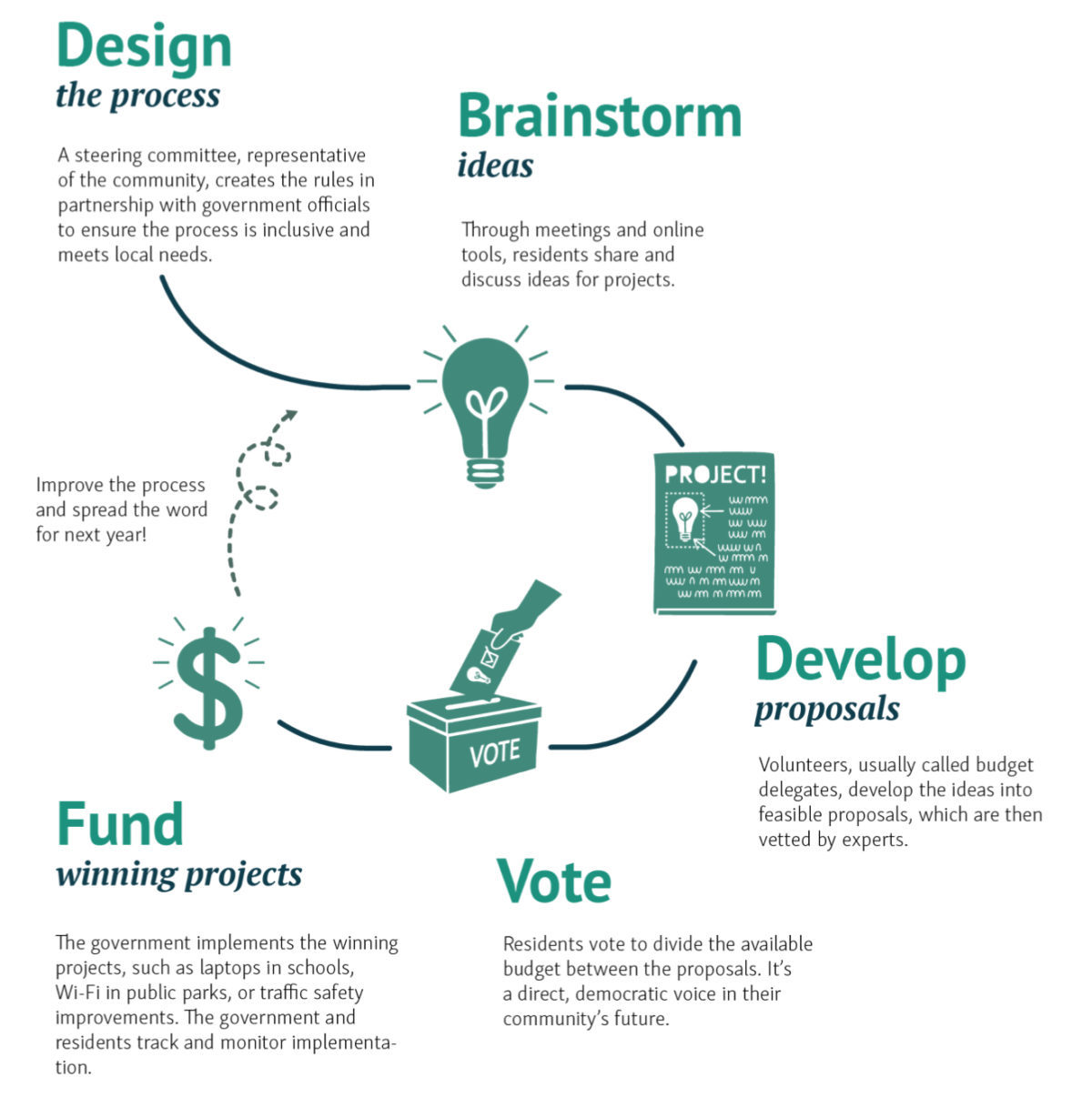

The Participatory Budgeting Process

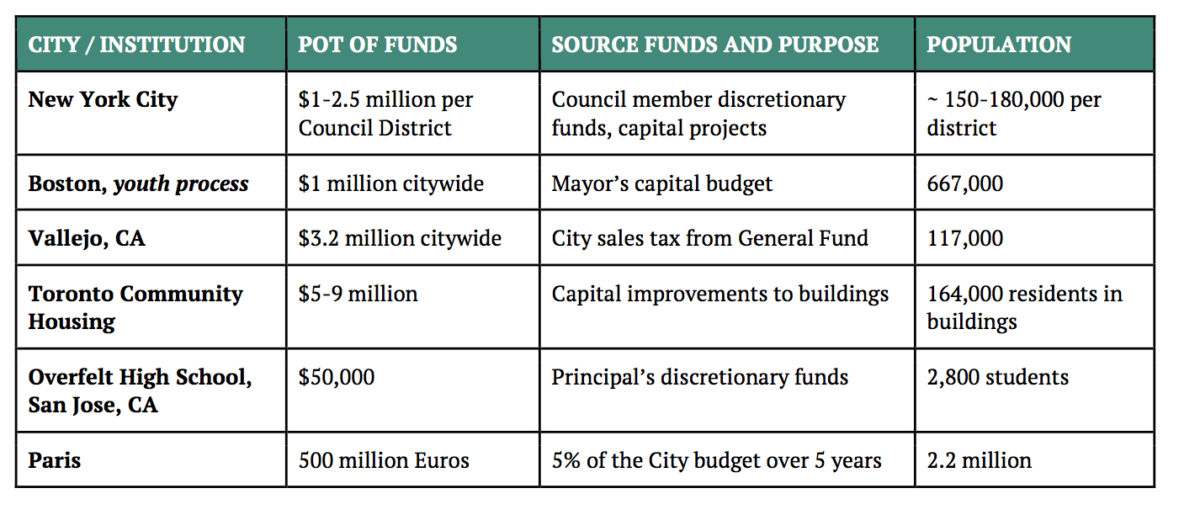

Participatory budgeting is typically an annual process in which funding in a municipal, institutional, or school-district budget is allocated for use in a community decision-making process. Participatory budgeting generally uses funds that are not already committed to essential or fixed expenses (such as employee salaries, approved contracts, pensions, or debt service, for example) and that can be used at the discretion of public officials.

The funds approved for use in a participatory-budgeting process typically represent only a small portion of a public budget, though participants often develop innovative ideas that help communities achieve a bigger impact with the same amount of funding, or increases in allocated funds will be made annually as local leaders and community members experience the benefits and impact of the process.

Importantly, participatory budgeting does not require the approval of new funding, just a change to how existing funding is allocated and used. For example, a school district may have $100,000 or $1,000,000 earmarked for investments in classroom technology, but administrators have not yet determined precisely how that approved funding will be spent. In this case, the district may use a participatory-budgeting process that involves teachers, students, and parents in determining how technology funding will be spent.

In many cases, participatory budgeting will prioritize funding streams—such as budget allocations for educational programming, affordable housing, public services, or community development—that are important to groups and constituencies that have been historically underrepresented in governmental decision-making. Other sources of funding might include budget allocations from federal programs such as the Community Development Block Grant Program or from state and local programs such as Community Benefit Agreements or Tax Increment Financing (TIF). In some cases, non-governmental sources of funding from philanthropic foundations, nonprofit organizations, private universities, or grassroots fundraising may be used if it is intended for the benefit of the public or certain stakeholder groups.

On average, between 1–15% of an annual municipal, district, or institutional budget may be allocated for a participatory decision-making process. Aa general guideline, the Participatory Budgeting Project recommends “starting with at least $1 million per ~100,000 residents, so that invitations to participate are compelling, the process has a visible impact on communities, and participants feel like it’s worth their time. While PB can be done with any pot of money, the larger the pot, the greater the likelihood that participants will leave feeling that the process could address their most pressing concerns.” For districts, schools, and smaller communities, even small amounts of money can have a large positive impact on youth, family, and community engagement.

The specific types of funding allocated for participatory budgeting can also influence who decides to participate by motivating certain interest groups to get involved. In addition, agencies and grassroots groups that have trusting, long-standing relationships with underrepresented communities—such as low-income populations, communities of color, immigrants, or youth—are often enlisted to help with outreach and recruitment or ensure that the process is designed in ways that make it accessible and equitable for people from diverse backgrounds.

In most cases, a participatory-budgeting process will not require changes in legal budgetary authority or legislation, but some city councils or school boards may choose to codify the process in local policies or statues, which can help build buy-in among local leaders, promote public transparency, or signal a long-term commitment to the inclusive budgeting process.

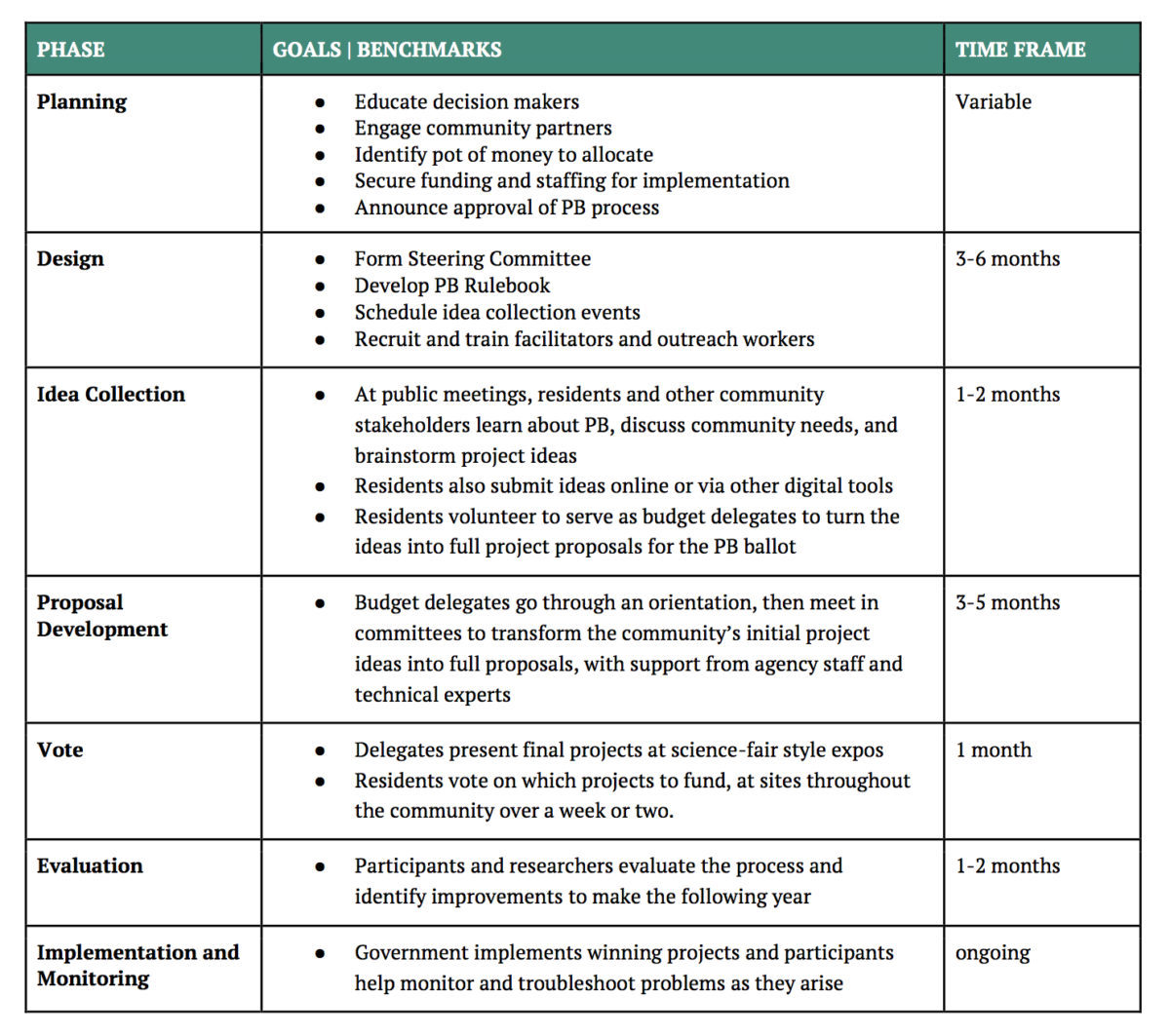

Once a budget has been identified and approved, a participatory-budgeting process can take between 3–6 months to design, and a typical cycle might take 5–8 months from conception to implementation of approved projects. While participatory budgeting programs are generally developed or customized by public institutions and local community partners, most follow a standard sequence of steps:

1. Planning (several weeks or months)

A participatory-budgeting process is typically initiated by a group of public officials, administrators, leaders, and/or organizers who educate local decision-makers about participatory budgeting, identify discretionary funding that can be to allocated for the process, secure approval to use funding, determine which paid staff will be assigned to the project, and announce approval of the funding and prospective launch of the process.

2. Design (3–6 months)

After funds have been approved volunteers from diverse professional and cultural backgrounds are recruited to lead and coordinate the process, a steering committee that is representative of the community is formed, a participatory-budgeting rulebook is created that describes the process and participation guidelines, public events are scheduled that give community members opportunities to learn about the process and how they can get involved, and organizers and facilitators who can reach out to historically marginalized groups and help coordinate and lead events are recruited and trained.

3. Idea Collection (1–2 months)

The steering committee then organizes public meetings during which residents and community stakeholders are informed about participatory budgeting, learn how the proposed process will work, discuss community needs and aspirations, and start brainstorming project ideas. The steering committee also begins identifying potential volunteer “budget delegates” who will form into teams and turn collected ideas into the full project proposals that will ultimately appear on the voting ballot. In some communities, residents and stakeholders may also submit ideas through online surveys and other digital tools.

4. Proposal Development (3–5 months)

Following the brainstorming process, the steering committee provides an orientation to the budget delegates, who then meet in teams and community groups to transform initial project ideas into viable proposals with support from public officials, administrators, and experts who understand which elements of a project may be technically feasible or infeasible and who can determine what specific projects will cost. Staff from various governmental departments may also be asked to provide information to delegates on projected costs or feasibility, or they may be involved in refining or vetting project proposals before they are finalized for public presentation.

5. Voting (1 month)

When the delegate teams finalize their proposals, the projects are presented at a science-fair style exposition open to the community, and residents are given an opportunity to vote on-site or online for the projects they want to see funded. The projects that receive the most votes are announced and funding is approved.

6. Evaluation (1–2 months)

Following the community vote, local officials and participants, sometimes working in collaboration with researchers or professional evaluators, reflect on the process, survey participants, or analyze data to identify improvements that can be made the following year’s process. Formal evaluation may also continue through the implementation phase to measure longer-term results and impact.

7. Implementation and Monitoring (Ongoing)

The municipality, agency, district, or institution then funds and implements the winning projects, and community participants remain involved to help monitor progress and troubleshoot problems as they arise.

Acknowledgments

Organizing Engagement thanks Shari Davis and Elizabeth Crews for their contributions to improving this introduction, and the Participatory Budgeting Project for permission to republish images from their website and publications.

Creative Commons

This work by Organizing Engagement is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. When excerpting, adapting, or republishing content from this resource, users should cite the source texts and confirm that all quotations and excerpts are accurately presented.