In Public Participation for 21st Century Democracy, a comprehensive text on the theory, scholarship, and practice of public participation in democratic decision-making and problem-solving, Tina Nabatchi and Matt Leighninger propose a simple framework for categorizing the purpose and goals of different engagement strategies. The Building Blocks of Engagement model describes six general forms of educational engagement that, when they work in concert, can create the foundation for an effective system of student, family, and community engagement and participation.

“The potential for public participation in education may be greater than for any other issue. The school system is a large institutional presence in almost every community, and education often attracts more attention, allegiance, and concern than any other public issue…. We know that participation in education can produce a wide variety of benefits, from better school policymaking to the success of individual students. However, despite the fact that most school systems support a wide array of engagement avenues and arenas, the inadequacy of that infrastructure—and the processes used within it—has prevented most communities from capitalizing on the potential of public participation in education.”

Tina Nabatchi and Matt Leighninger, Public Participation for 21st Century Democracy

Nabatchi and Leighninger write that “education is fundamental to participation and democracy for one simple reason: people care about kids. The way we educate young people is a subject of intense hope and concern for many of us, regardless of whether we are parents ourselves.” In Public Participation for 21st Century Democracy, the authors offer several additional reasons for why educational engagement, in particular, is central to the functioning of modern democratic systems:

- “We look to our education systems as the training grounds for future citizens, giving students the skills, knowledge, and experiences they need to be members of a democracy.”

- “Creating an environment in which their children can thrive is a tremendously compelling incentive for parents. For many people, it is the primary motivation pulling them into public life—an onramp or even a precondition for their participation in other issues.”

- “As physical spaces, schools can be natural hubs for community; they are sometimes used for public meetings and other gatherings.”

- “In many places, the school system is the largest employer and represents the largest expenditure of tax revenues; a school budget decision may be the most significant public finance issue faced by a community.”

- “In addition to being the leaders of tomorrow, young people can be effective leaders today—students can be participants not only in improving their own education, but in other aspects of public life.”

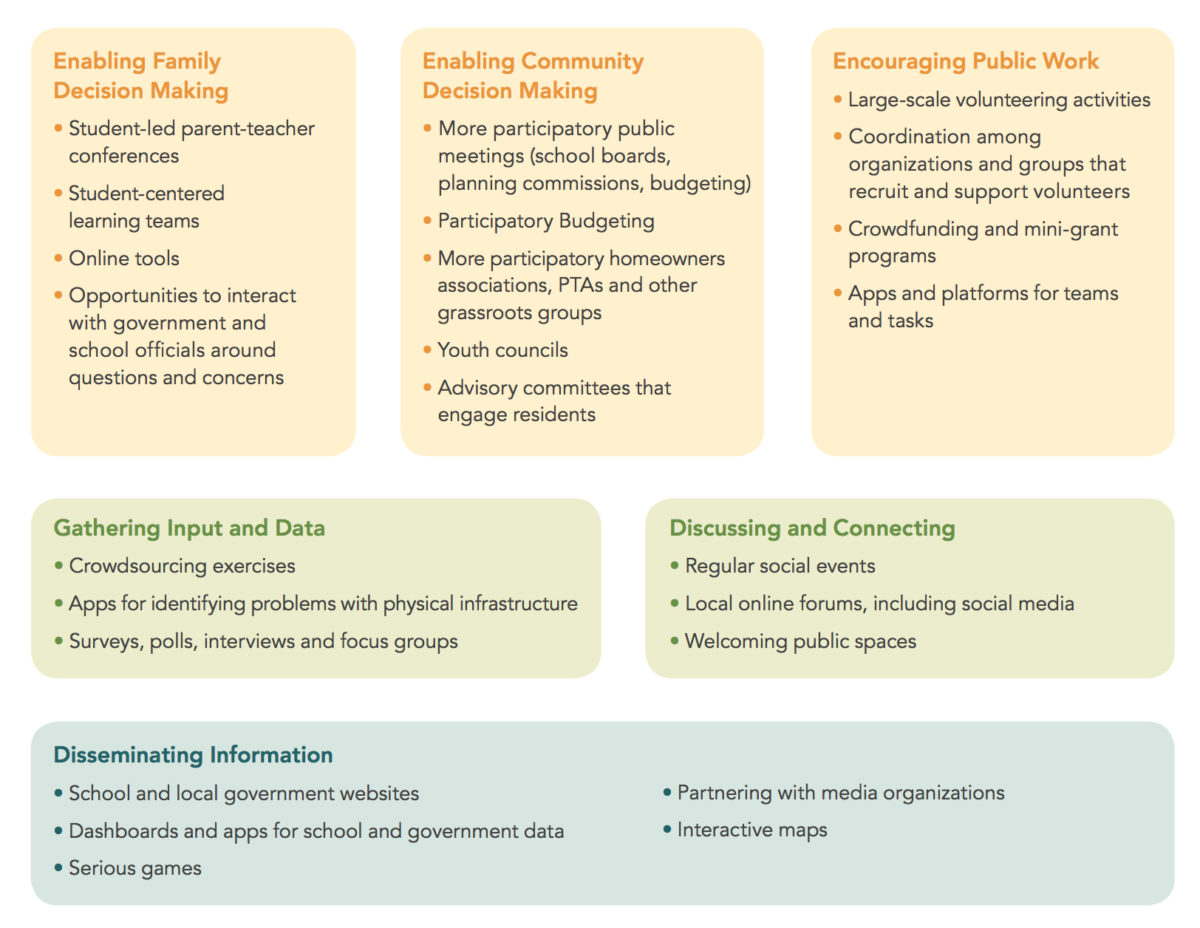

Proposed by Tina Nabatchi and Matt Leighninger in Public Participation for 21st Century Democracy, the Building Blocks of Engagement framework describes six foundational components of a systems-wide approach to student, family, and community engagement in education. The model also includes illustrative examples of engagement strategies for each “building block.” Image source: Strengthening and Sustaining Public Engagement in Vermont: A Planning Guide for Communities.

The Building Blocks of Engagement

One of the organizing principles of the Building Blocks of Engagement model is that different forms of engagement are better suited to some purposes than others, and that local leaders should understand the strengths and limitations of each “building block” so that they can utilize the right approach for a particular problem or goal.

In their introduction to the Building Blocks of Engagement, Tina Nabatchi and Matt Leighninger make three important points:

- “Each of the six building blocks is necessary, at least to some extent, in any successful participation infrastructure. At first blush, this might seem overwhelming. However, many of the settings and tools for these activities already exist, at least to some degree, in every school district.”

- “Some of these settings, like parent groups and school boards, are central and versatile—they could potentially play a vital role in all six activities… But for most of the parents, school officials, and other participation leaders in charge of these existing settings, supporting participation more effectively will require changes—sometimes significant ones—in the way they operate and how they think about engagement.”

- “Meaningful and sustainable infrastructure for participation in education cannot be built overnight. It takes time, strategy, effort, and buy-in—not only from educators, parents, and students, but from the many other people and organizations in a community that have a vested interest in the success of young people (in other words, everyone).”

The six building blocks of engagement:

1. Disseminating Information

While “engagement” is typically viewed as a two-way process, and many engagement practitioners caution against “one-way” forms of communication, information dissemination is an essential component of any effective student, family, and community engagement strategy. Problems with one-way forms of communication tend to arise when local leaders rely largely or entirely on one-way communication or when they believe that merely communicating information qualifies as “engagement” (and thereby exempts them from having to do anything else).

Though engagement should be understood as a two-way process, it’s important to recognize that one-way communication plays an instrumental role in creating the conditions for effective two-way engagement. For example, engagement opportunities need to be promoted or people will not show up, and parents need to know what’s happening in their child’s school or they will be unable to make informed decisions that are in the best interests of their children.

More fundamentally, good decisions require good information—information that is factual, accurate, illuminating, and as unbiased as possible—and poor decisions often result from misunderstanding or misinformation. For example, it would be impossible to have a productive public conversation about a proposed school budget if the community is entirely uninformed about what’s actually in the budget. Importantly, when districts and schools communicate frequently and transparently, it tends to reduce many of the anxieties, tensions, and debates that often make other forms of engagement either more challenging or more urgently needed.

Historically, media outlets were the primary vehicle for informing the public about their local schools, but Nabatchi and Leighninger note that the internet and other communications technologies have dramatically improved the ability of school leaders to communicate directly with their students, families, and stakeholders. Examples of such technologies include not only school websites, social media, or email newsletters, but also online “dashboards” that present school data in easy-to-understand formats, student-information systems that allow parents to access up-to-the-minute information about their child’s academic progress, or messaging systems that send news and notifications to parents and families via mobile texts or audio recordings.

2. Gathering Input and Data

If the goal of information dissemination is to keep students, families, and community members more informed about their district or school, then collecting input, feedback, and other data helps district and school leaders remain informed about their students, families, and community members. Strategies such as polls, surveys, and focus groups have historically been used to assess public opinion and inform political, governmental, or educational decisions, and many districts and schools regularly use these strategies—particularly surveys—to gauge student, family, and staff views on a variety of issues, such as school culture or classroom teaching.

Like information dissemination, data collection is often a one-way process, and problems can arise when district, school, or community leaders ask people for their time and opinions, but then fail to communicate back to the community the results of the data-collection process or how it influenced decision-making. When data-collection is unaccompanied by this kind of feedback loop, students, families, and communities are more likely to view surveys or focus groups as a waste of time, and they are also likely to be frustrated or angry if they feel their concerns were not heard or acted upon.

Data-collection processes can, however, be a highly effective component of a comprehensive engagement strategy or system. For example, local leaders can use the results of polls, surveys, focus groups, and other forms of data, such as demographic or socioeconomic data, to determine what community members are concerned about or passionate about, or where the urgent problems exist in the school system or community.

The results of a data-collection and -analysis process can then used to inform the design and goals of an engagement process. For example, a school-culture survey might bring to light systemic problems, which can then become topics for a series of dialogues focused on developing solutions in partnership with students, families, and staff members.

In addition to more traditional forms of data collection, Nabatchi and Leighninger point out that new technologies now offer more creative and interactive ways to collect input, feedback, and other data. A variety of inexpensive and readily available online and mobile applications enable local leaders to “crowdsource” information and ideas by, for example, allowing community members to vote on and rank different proposals or submit photos of physical problems with school facilities so they can be fixed.

3. Discussing and Connecting

Nabatchi and Leighninger write that the “social aspects of participation are often overlooked, but they are critical for establishing the kinds of relationships that communities need to improve the quality of education.” While they are not often considered to be forms of “engagement,” informal interactions can produce the same outcomes that are often sought by local leaders deploying intentional engagement strategies—e.g., trusting relationships are formed, greater cross-cultural understanding takes hold, etc. For this reason, districts, schools, and communities should consider public spaces, social events, and other in-person or online forums to be essential components of a comprehensive student, family, and community engagement strategy.

When community members routinely socialize and interact, particularly across cultural divides, it creates an environment in which people may be more inclined and motivated to participate in planned activities. In addition, it’s important that engagement not be exclusively seen as “work”—i.e., something that is challenging, time-consuming, and needs to result in a particular outcome.

Because socializing, celebrating, or eating food are powerful motivators, local leaders can also increase community participation by blending formal and informal engagement strategies, and by being more intentional about engagement in informal settings. For example, school leaders can train staff to employ effective welcoming strategies with parents and families, community groups can be invited to use school facilities during evenings or weekends, or social events can be modified to incorporate opportunities for cross-cultural dialogue and relationship-building.

→ For a related discussion, see the celebration principle of organizing, engagement, and equity

4. Enabling Student and Family Decision-Making

According to Nabatchi and Leighninger, “People want choices, and the choices they care most about are generally the ones that will have the greatest impact on their lives or those of their children. When students and parents have the opportunity to make those choices, with the input and guidance of educators, using information they trust, they take greater ownership over other aspects of the education system. It can also help them make better and wiser choices, which in turn may have positive impacts on the schools and school systems.”

When students, parents, and family members are given opportunities to participate more actively in the teaching and learning decisions, for example, it can improve academic motivation, progress, and aspirations for students, and it can help parents and teachers see one another as partners in the education of children. Examples of student and family participation in decision-making include student-led conferences, parent-teacher teams, and other partnerships, practices, or projects that give individual students or family members leadership or decision-making roles in the educational process.

5. Enabling Community Decision-Making

Nabatchi and Leighninger write that “the infrastructure for participation in a school system would be inadequate if it failed to help the district address major policy decisions and develop long-term strategic plans. Because they are likely the most visible and high-stakes examples of participation, opportunities to make community decisions about education have an important impact on the legitimacy of engagement overall.”

When students, families, and community members are given opportunities to participate in school governance or an important decision-making process, those opportunities often produce greater levels of trust in school leadership and increased support for school policies, proposals, or budgets. Because community members often want to make a positive contribution to their schools and community, creating leadership and decision-making opportunities for stakeholders can engender feelings of motivation, empowerment, and ownership that are central to successful engagement.

In recent years, political polarization and other factors have increased hostility toward school leaders and community tensions about local educational expenditures, which has eroded historically strong relationships between public schools and their community. As Nabatchi and Leighninger note, community-involved decision-making can help to legitimize school decisions, and thereby reduce school-community tensions or reinvigorate community support, financially and otherwise, for public schools.

When families and community members are left out of decisions that impact them or their children, they are more likely to feel skeptical, frustrated, or angry, but when they are involved, in small or large ways, they are more likely to feel that their concerns have been addressed (or at least considered) and more likely to feel a sense of ownership or pride in the outcome. Examples of community participation in decision-making include student, family, or community advisory committees, participatory budgeting, community-involved strategic planning, student participation in administrator hiring decisions, and other strategies that incorporate community participation into a formal school-governance structure or a short-term governance process.

6. Encouraging Public Work

In the Building Blocks of Engagement model, public work is defined as activities in which students, families, and community members “expend time, energy, and sweat equity in ways that will improve the quality of education.” Although acts of public work may not provide decision-making opportunities to community members, they can nevertheless produce similar positive outcomes, including greater motivation to participate in school activities, increased confidence in school leaders or administrative decisions, and greater support for school programs or budgets.

Parent volunteer programs and fundraising drives are perhaps the most traditional and familiar opportunities for public work in education, but public work can take a wide variety of forms, including community-based learning or service-learning projects in which youth can earn academic credit by, for example, learning about an important community problem, developing a proposal to solve the problem, and volunteering for an organization actively working to address the problem. Public work may also take the form of educators volunteering for community organizations, participating on the boards of local nonprofits, or coordinating community programs and campaigns.

Developing the Infrastructure for Systemic Engagement

In Public Participation for 21st Century Democracy, Tina Nabatchi and Matt Leighninger discuss some of the systems-level features that school administrators, school board members, public officials, program directors, and other local leaders need to consider when developing a comprehensive student, family, and community engagement strategy:

1. Training and Skill Development

Educator, youth, family, and community leaders typically need training in the strategies and practices of effective engagement, whether it’s strategies for organizing inclusive and welcoming events, facilitating public discussions, or understanding and accommodating cultural differences.

2. Professional Incentives

Nabatchi and Leighninger argue that “people need skills, but they also need incentives. For the most part, educators are not rewarded for being good at public participation; how teachers interact with parents or how administrators interact with the public is seldom incorporated directly into rubrics for calculating pay raises, promotions, or other modes of professional advancement.”

In addition, student, family, and community engagement is rarely an explicit part of an educator’s job description, and hiring processes for administrators, teachers, and other staff rarely include an assessment of engagement experience, skills, or credentials. Any effective systems-wide approach to engagement must include both professional incentives and formal job-embedded engagement expectations. Nabatchi and Leighninger also note that “non-monetary incentives, such as recognition, awards, and forms of authority and legitimacy, can also be effective.”

3. Policies and Procedures

If engagement is not built into the policies and procedures of a district or school, it is unlikely to be prioritized in busy school systems that are juggling numerous important priorities every day. Because educators regularly face urgent demands for their time and attention, it’s easy for engagement to be sidelined by those demands or categorized as “optional.” While engagement can produce immediate and visible results, many of the most important outcomes of engagement can take months or years to materialize—for example, reestablishing trust in a community that feels the school system has failed them.

For these reasons, Nabatchi and Leighninger suggest, engagement is most effective when it is built into every part of the system, and when policies and procedures require board members, administrators, teachers, and staff to incorporate engagement into the day-to-day operation of the district or school.

4. Funding and Budgeting

Nabatchi and Leighninger write that “reading a long list of potential participation activities can bring on sticker shock” for school administrators, board members, program directors, and others in charge of allocating limited funding. “Some may argue that, even if parents and other community leaders pitch in, the financial cost to the school of maintaining such a wide array of participation opportunities is prohibitive,” the authors continue. “However, others might argue that participation is key to sustaining or growing the pool of financial resources available to school districts—because the resources will be coming (or not) from participating parents or community members.”

Nabatchi and Leighninger make two points in response: (a) during a financial shortfall or crisis, communications and engagement positions are often the first to get cut, and yet it’s precisely these positions that help schools weather a financial crisis, and (b) that the costs of stronger engagement don’t need to be excessive or unmanageable, particularly when engagement is incorporated into existing programs, events, and professional roles.

Acknowledgments

Organizing Engagement thanks Matt Leighninger for his contributions to improving this introduction, and Public Agenda for permission to republish an image from Strengthening and Sustaining Public Engagement in Vermont: A Planning Guide for Communities.

References

Leighninger, M. (2017). Strengthening and sustaining public engagement in Vermont: A planning guide for communities. Washington, DC: Public Agenda

Nabatchi, T. & Leighninger, M. (2015). Public Participation for 21st Century Democracy. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Creative Commons

This work by Organizing Engagement is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. When excerpting, adapting, or republishing content from this resource, users should cite the source texts and confirm that all quotations and excerpts are accurately presented.