Proposed by Robert Silverman in a 2005 article in the journal Community Development, the Citizen Participation Continuum builds on previous models of participation, notably Sherry Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation, but limits its scope to the specific roles that community-development corporations (CDCs) and community-based organizations (CBOs) play in facilitating the participation of community members in local school, civic, or municipal decision-making.

“CDCs represent a unique case to examine, since they are located near the center of the citizen participation continuum. This is a place where the conflict between instrumental and grassroots forms of participation is the most intense. In essence, CDCs are caught in the middle of participatory techniques used to facilitate program implementation and the long-standing value of grassroots activism. How CDCs respond to these pressures illuminates potential strategies to reform community-based organizations and enhance citizen participation in the future.”

Robert Silverman, “Caught in the Middle: Community Development Corporations (CDCs) and the Conflict between Grassroots and Instrumental Forms of Citizen Participation,” Community Development

As Silverman explains, he developed the Citizen Participation Continuum in response to “the growing interest in implementing public policy through community-based organizations like CDCs, since they are considered to be more responsive to grassroots constituencies than institutions traditionally involved in the formulation and implementation of local public policy.” In addition to administering programs supported by fees or private grants and gifts, CDCs and CBOs are increasingly the beneficiaries of state and federal grants and charged with implementing publicly funded programs at the community level.

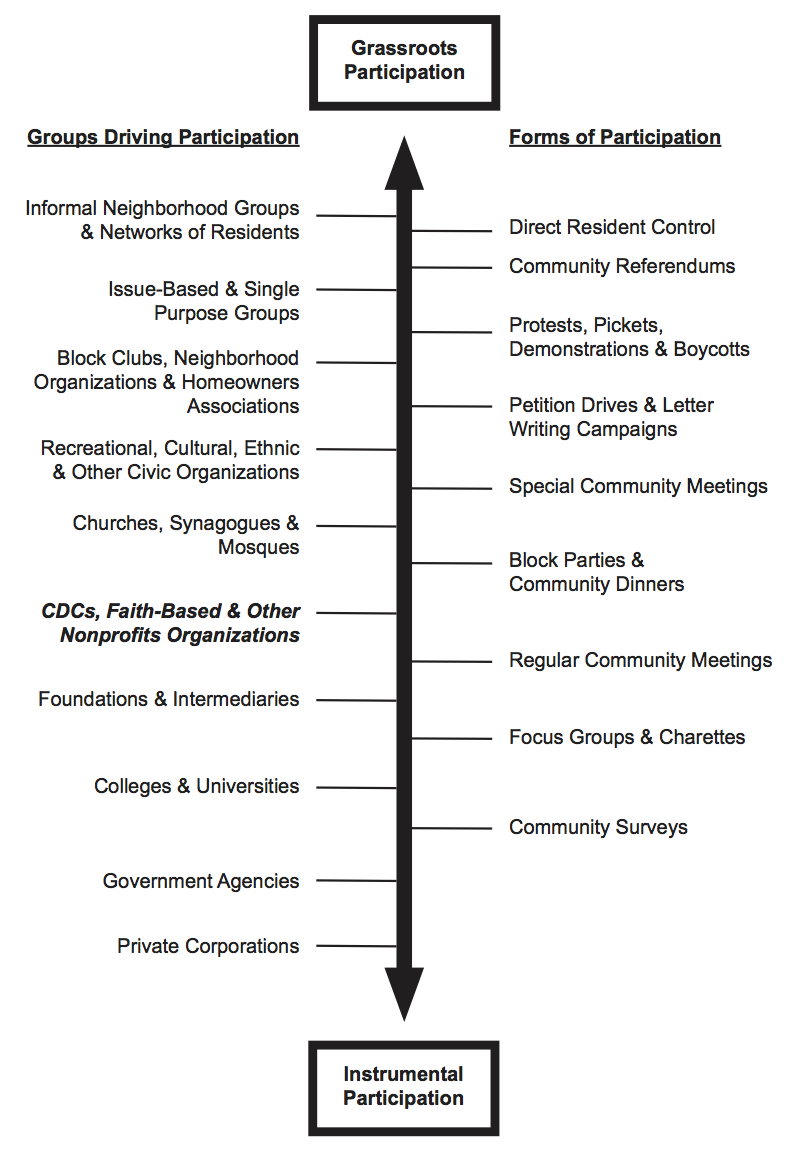

The purpose of the continuum, according to Silverman, is to help “define the range of potential grassroots activities a community-based organization can pursue and the participatory outcomes they can produce,” as well as increase understanding of “where organizations fall along the citizen participation continuum in order to chart a course for expanding citizen input in community development activities.”

To this end, Silverman proposes two “extreme forms of citizen participation,” or what he calls “ideal-types” because “neither type of citizen participation in its pure form is found in an organization…citizen participation in most community-based organizations tends to fall at an intermediate point between the continuum’s two extremes.” In other words, the model—while presenting two conceptual poles—is intended to help local organizational leaders and their community partners navigate the murky, complex, and often contentious decisions that make up the day-to-day practice of citizen participation in local policy, community programming, and grassroots activism.

The Citizen Participation Continuum

While the Citizen Participation Continuum is presented vertically, Silverman’s model is not meant to be interpreted as a developmental or hierarchical progression—i.e., the continuum could have been presented horizontally without altering its meaning.

Unlike earlier ladders of participation or empowerment, such as Roger Hart’s Ladder of Children’s Participation and Elizabeth Roche’s Ladder of Empowerment, the Citizen Participation Continuum does not describe degrees of participatory power or agency, but rather the common forms of citizen participation and the range of groups, associations, and organizations that provide, shape, or determine opportunities for community-member participation.

The two poles of Silverman’s Citizen Participation Continuum:

1. Instrumental Participation

Instrumental forms of participation encompass the operational and programmatic scope of a CDC or CBO, and therefore citizen participation is often limited to the more narrow range of activities that fall within the organization’s mission and programming, or that are supported by the organization’s funding, staff, and facilities. According to Silverman, “This type of participation is argued to be task-oriented, with a focus on the completion of specific projects or programs in which a community-based organization is engaged. Accordingly, instrumental participation is predicted to be driven by community-based organizations that are administering specific projects and programs. Organizational representatives drive this type of participation in order to inform and consult residents about upcoming project and program activities.”

2. Grassroots Participation

Grassroots forms of participation encompass a broader array of possible participatory actions that may be undertaken by CDCs and CBOs, undertaken with support from or in partnership with CDCs and CBOs, or undertaken independently by groups and associations that are not legal nonprofits. As Silverman explains, grassroots participation will often “emerge in response to neighborhood threats, which residents perceive because of disinvestment, institutional neglect, or the development of noxious facilities in their communities. Unlike instrumental participation, grassroots participation is driven by local residents interested in increasing the visibility of perceived neighborhood threats and defending their turf. As a result, residents often take action when neighborhood threats are highly salient, and they utilize grassroots participation to influence the agenda of community-based organizations.”

While instrumental participation, like grassroots participation, may be motivated by a cause, mission, threat, crisis, or political objective, the range of participatory activities are typically limited by the operational concerns of the organization, such as budgetary constraints, staff capacity and expertise, the priorities and expectations of grant programs, or laws prohibiting certain forms of lobbying by nonprofits.

On the other hand, grassroots participation, while potentially strategically and tactically unconstrained, may lack the influence, funding, expertise, or other resources available to established CDCs and CBOs. In other words, instrumental participation is generally shaped by operational limitations (e.g., budgets, staffing, program scope, contractual priorities, grant deliverables, etc.) whereas grassroots participation is generally shaped by resource limitations (e.g., political influence, funding sources, volunteer capacity, etc.).

As Silverman explains, “Formal societal-level organizations such as private corporations and government agencies are associated with instrumental participation, although informal parochial-level organizations such as block clubs and informal neighborhood groups are associated with grassroots participation. In addition to predicting which types of organizations would be located at the extremes of the continuum, this framework predicts that organizations like CDCs would fall in an intermediate position along the continuum. In other words, community-based organizations and other nonprofits are predicted to face conflicting pressures to balance the necessity of using instrumental forms of citizen participation against demands for greater grassroots participation.”

The Citizen Participation Continuum is complemented by a study of CDCs in Detroit, Michigan, which included in-depth interviews with executive directors. In his final analysis, Silverman articulates the opportunities for CDCs to play a more affirmative role in facilitating, supporting, and empowering grassroots participation:

“Participation in Detroit’s CDCs had a tendency to fall at an intermediate point along the citizen participation continuum…. In instances where grassroots issues were brought to the attention of CDCs, there was a tendency to reframe them in the context of an organization’s instrumental goals. In the short-term, demands for grassroots participation were balanced with instrumental participation. In the long-term, CDCs returned to an intermediate position on the citizen participation continuum. In order for CDCs and organizations like them to move in the direction of institutionalizing greater grassroots participation, two fundamental changes must occur.

First, local nonprofits must become more proactive in their efforts to promote grassroots participation. In essence, more resources and time must be committed to community-organizing and capacity-building.

Second, this renewed emphasis on community-organizing and capacity-building must be reinforced with stronger institutional mandates for grassroots participation in the policy process.

In other words, foundations, government agencies, and funding intermediaries need to increase funding levels for community-organizing and capacity-building activities. These institutions also need to require such activities as a condition to receive resources for project and program implementation. Strengthening external mandates for community-organizing and capacity-building activities will reinforce the long-standing value of grassroots participation within CDCs and other community-based organizations.”

Acknowledgments

Organizing Engagement thanks Robert Silverman for his contributions to improving this introduction.

References

Silverman, R. M. (2005). Caught in the middle: Community development corporations (CDCs) and the conflict between grassroots and instrumental forms of citizen participation. Community Development: Journal of the Community Development Society, 36(2), 35–51.

Creative Commons

This work by Organizing Engagement is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. When excerpting, adapting, or republishing content from this resource, users should cite the source texts and confirm that all quotations and excerpts are accurately presented.