In 2009, the researchers Neema Kudva and David Driskell proposed the Five Key Dimensions of Participation as Spatial Practice in the journal Community Development. The model is specifically focused on elucidating the features of adult-led organizations working to promote positive youth development, leadership, and participation.

Cast as “spatial practice,” the five dimensions “articulate a vocabulary and structure through which we can better understand the ways in which organizations create spaces for participation and thereby shape participatory processes.” If adult allies, practitioners, and organizational leaders do not intentionally create the conditions for positive youth development, leadership, and participation, most default adult-led spaces will suffer from conventional or habitual power imbalances that undermine authentic youth participation and empowerment.

“Participation in community development and planning is concerned with issues of power, and focuses its attention on the structures, processes, and methods through which power imbalances are alleviated (or not) and decisions are made with at least an attempt toward due consideration to the interests of those affected. What we recognize as ‘participatory’ depends on values, moral judgments, perceived goals, and intended outcomes. As importantly, there is always some debate on whether it is enough that space be provided for voicing concerns regardless of who might or might not speak or be heard, or whether the project of participation requires a more active approach, in which the unheard are sought out and ‘given voice.’”

Neema Kudva and David Driskell, “Creating Space for Participation,” Community Development

Importantly, the authors note that their model is “the product of ongoing dialog between our fieldwork and observations on the one hand, and the theoretical literature on organizations and participation on the other.” While Kudva and Driskell’s model draws on learning from a five-site Growing Up in Cities initiative in New York (led by Driskell), which supported young people’s participation in community research and action, it is rooted in their combined experience in community-based planning with public and private agencies in a wide variety of locations in the United States, India, and other countries.

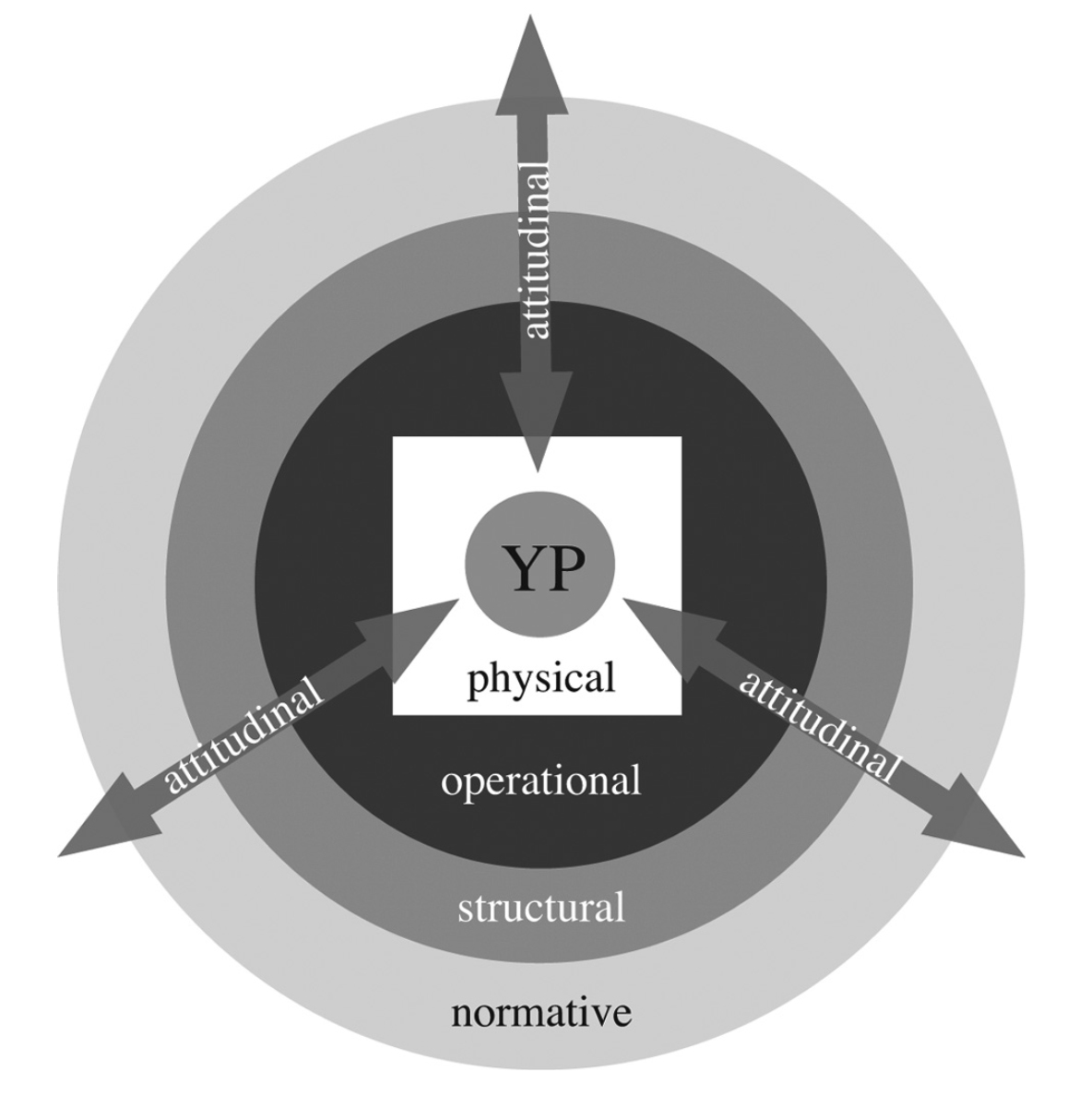

Five Key Dimensions of Participation as Spatial Practice Model

In their article, Kudva and Driskell discuss their rationale for developing the framework: “Analyzing participation as a spatial practice helps us to understand the ways in which these different dimensions and the spaces they create exist in relation to each other; an issue where conventional organizational analysis falls short.

The five key dimensions we note intersect differently at various points in time to both open and close-off opportunities for different forms of participation within a fluid, changing internal environment. Understanding the organization as framed by norms and values, organizational structures and physical plant, as well as by the interpersonal relations and identities of those who work within it, gives shape to these five dimensions that create participatory space.”

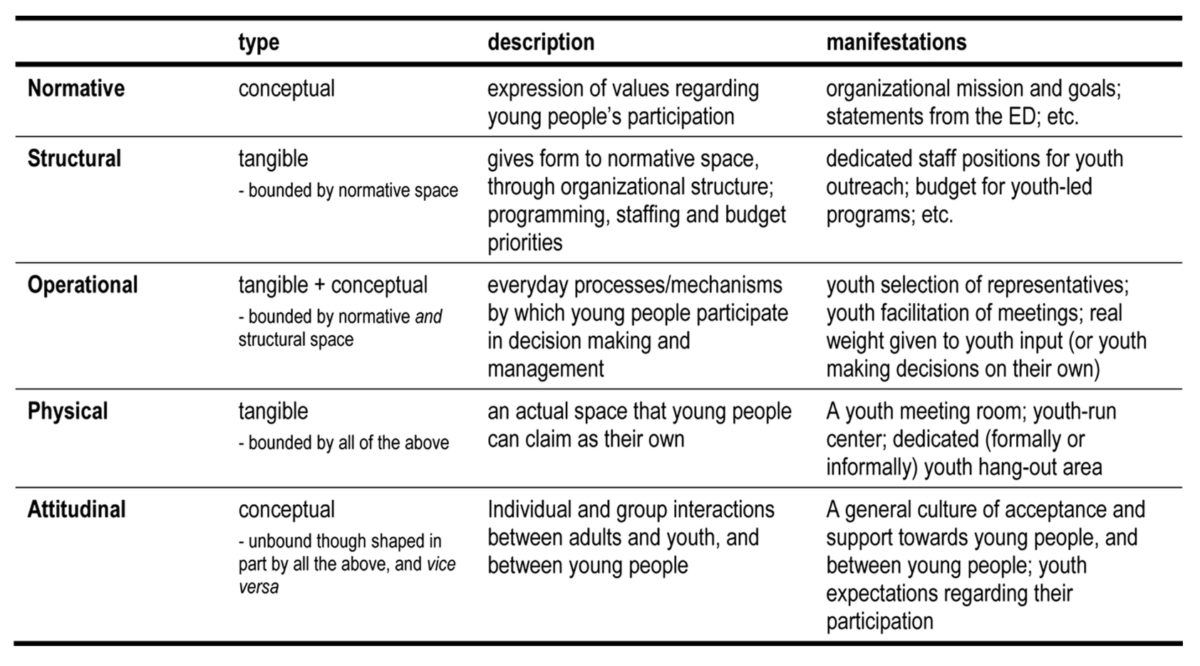

The five key dimensions of participation:

1. Normative

The normative dimension encompasses the “organization’s expression of values as it pertains to young people and their participation.” The normative dimension is the organization’s “public declaration” of its values and purpose, including the status, roles, and value of youth in that organization.

Examples include public expressions such as vision and mission statements, website content, presentations, speeches, and written policies. Kudva and Driskell note that even though the normative dimension is conceptual, it is nevertheless “seen, heard, and felt.” In addition, the normative dimensions are, in many ways, “the most critical spatial dimension for participation in organizational practice” because “without the normative space of participation, there is little room for much else.” The normative dimension, therefore, operates as a container for other dimensions: it creates the philosophical space—the standards, norms, and expectations—that allow positive youth participation and empowerment to take hold.

2. Structural

The structural dimension encompasses an organization’s budget, programming, staffing, and related priorities. As Kudva and Driskell point out, “Without appropriate structures, normative declarations ring empty, and efforts toward operationalizing participation can go adrift…. In other words, participation doesn’t just happen. Someone has to facilitate it. Someone has to pay for it. Someone should even be leading critical reflections on how to do it better.”

Examples of the structural factors that facilitate positive youth participation and empowerment include “dedicated staff positions for youth outreach and facilitation; resource allocations for youth training and youth-led program evaluations; and projects that are specifically intended to be either youth-run or youth-directed.” If the normative dimension creates the organization’s philosophical space, the structural dimension creates the organization’s programmatic space—its policies, priorities, and resource allocations.

3. Operational

The operational dimension encompasses “the everyday practice of the organization in action” and “the mechanisms by which young people have a meaningful say in organizational decision making and management.” While the operational dimension is “embedded within structural space,” the operational factors are “concerned with actual decision-making practices rather than the codified structures for them.

Kudva and Driskell provide an example: “While creation of a youth advisory board defines a structural space for youth input, the actual ways in which the advisory board works—its operational dimension—shapes its effectiveness as a space of participation.” If the structural dimension creates the organization’s programmatic space, the operational dimension creates the organization’s decision-making space—it’s day-to-day process for executing on philosophical and structural priorities.

4. Physical

The physical dimension encompasses “the provision of an actual space (be it a separate room, building, outdoor area, or even a cubicle) that young people can claim as their own, where they can work independently as well as in collaboration with adults.” Kudva and Driskell note, however, that “while the physical space for young people’s participation does not require a youth-only zone, it does call for a designated territory in which young people are clearly in-charge, and where they can ‘‘hang out’’ on their own terms.”

If the operational dimension creates the organization’s decision-making space, the physical dimension creates physical space in which youth participation actually occurs. As the authors note, “While participatory practice with young people may exist without physical space, its absence typically undercuts the form and substance their participation might otherwise take.”

5. Attitudinal

The attitudinal dimension encompasses “the multiform interactions and identities rooted in interpersonal relations,” the “dynamics of interactions between adults and young people as well as between young people themselves,” and the “young people’s own expectations of their right to participate, and their ability and commitment to claim that right.” Unlike the other four dimensions, which are nested in the model—i.e., the normative circumscribes and shapes the structural, the structural circumscribes and shapes the operational, and so on—the attitudinal dimension transects all the dimensions.

According to Kudva and Driskell, “Attitudinal space, buffeted by individual attitudes and personalities, is the most fluid and immeasurable space of participation, but also the most commonly identified barrier to meaningful participation.” While the attitudinal dimension is expressed through the culture of an organization—how youth are generally treated, supported, or empowered, for example—attitudinal influences are also expressed in interpersonal adult-adult, adult-youth, and youth-youth interactions. For example, while an organizational culture may generally present as inclusive, supportive, and empowering to youth, it’s possible for some problematic adult-youth relationships, or negative peer-to-peer interactions, to subvert the general positivity of the organizational culture, and therefore become barriers to participation.

Kudva and Driskell close their article with the following guidance:

“We hope to contribute to a larger project of refocusing debates on participation toward more careful consideration of the deliberate choices that shape organizations and to emphatically underscore the point: participation does not just happen. The design of public institutions and organizational practices serve to facilitate or constrain meaningful and sustained participation. As Fung reminds us, this is the result of ‘deliberate choices, rather than taken-for-granted habits.’”

Acknowledgments

Organizing Engagement thanks Neema Kudva for her contributions to improving this introduction.

References

Fung, A. (2003). Recipes for public spheres: Eight institutional design choices and their consequences. The Journal of Political Philosophy, 11(3), 338–367.

Kudva, N. & Driskell, D. (2009). Creating space for participation: The role of organizational practice in structuring youth participation. Community Development, 40(4), 367–380.

Creative Commons

This work by Organizing Engagement is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. When excerpting, adapting, or republishing content from this resource, users should cite the source texts and confirm that all quotations and excerpts are accurately presented.