First developed by Joyce Epstein and collaborators in the early 1990s, the Framework of Six Types of Involvement—sometimes called the “School-Family-Community Partnership Model”—has undergone revisions in the intervening years, though the foundational elements of the framework have remained consistent. Epstein’s Framework of Six Types of Involvement is one of the most influential models in the field of school, family, and community engagement and partnership.

To support ongoing research and practice related to school, family, and community partnerships, Epstein and colleagues founded the Center on School, Family, and Community Partnerships and the National Network of Partnership Schools, which are part of the Center for Social Organization of Schools in the School of Education at Johns Hopkins University.

“The way schools care about children is reflected in the way schools care about the children’s families. If educators view children simply as students, they are likely to see the family as separate from the school. That is, the family is expected to do its job and leave the education of children to the schools. If educators view students as children, they are likely to see both the family and the community as partners with the school in children’s education and development. Partners recognize their shared interests in and responsibilities for children, and they work together to create better programs and opportunities for students.”

Joyce Epstein, “School/Family/Community Partnerships,” Phi Delta Kappan

The most recent version of the Framework of Six Types of Involvement is described in School, Family, and Community Partnerships: Your Handbook for Action (4th Edition, 2019), which is co-authored by Epstein and several collaborators: Mavis G. Sanders, Steven B. Sheldon, Beth S. Simon, Karen Clark Salinas, Natalie Rodriguez Jansorn, Frances L. Van Voorhis, Cecelia S. Martin, Brenda G. Thomas, Marsha D. Greenfeld, Darcy J. Hutchins, and Kenyatta J. Williams.

In addition to the framework introduced here, the handbook outlines a comprehensive model of school-family-community partnerships that includes several components, including the development of a school-based action team that can lead partnership initiatives, the creation and implementation of an action plan outlining partnership strategies and programs, the evaluation of quality and progress, and the continual improvement of school-family-community partnerships from year to year. The authors note that the Framework of Six Types of Involvement is intended to support the development and implementation of a systemic approach to partnerships, ideally one that cultivates a “culture of partnerships” throughout a district or school.

The Framework of Six Types of Involvement builds off Epstein’s theory of overlapping spheres of influence. The theory distinguishes an interdependent view of school-family-community influences from what could be considered a separate view of influence. Epstein explains the theory with an example:

“In some schools there are still educators who say, ‘If the family would just do its job, we could do our job.’ And there are still families who say, ‘I raised this child; now it is your job to educate her.’ These words embody a view of separate spheres of influence. Other educators say, ‘I cannot do my job without the help of my students’ families and the support of this community.’ And some parents say, ‘I really need to know what is happening in school in order to help my child.’ These phrases embody the theory of overlapping spheres of influence.”

In other words, the most effective school-family-community partnerships—i.e., those that have the greatest positive influence on a student’s social, emotional, cognitive, and educational development and thriving—recognize that the three primary “spheres” of influence do not operate independently of one another, but are mutually reinforcing—or mutually undermining. Epstein further explains the theory by describing how authentic school-family-community partnerships (i.e., those that are positively mutually reinforcing) work in practice:

- Family-Like Schools: “In a partnership, teachers and administrators create more family-like schools. A family-like school recognizes each child’s individuality and makes each child feel special and included. Family-like schools welcome all families, not just those that are easy to reach.”

- School-Like Families: “In a partnership, parents create more school-like families. A school-like family recognizes that each child is also a student. Families reinforce the importance of school, homework, and activities that build student skills and feelings of success.”

- School- and Family-Like Communities: “Communities, including groups of parents working together, create school-like opportunities, events, and programs that reinforce, recognize, and reward students for good progress, creativity, contributions, and excellence. Communities also create family-like settings, services, and events to enable families to better support their children.

The Framework of Six Types of Involvement is based on decades of research and practice in the fields of educational engagement and school-family-community partnerships. Summarizing the large body of empirical evidence supporting the model, Epstein provides the following helpful synopsis of a few patterns identified in the research literature:

- “Partnerships tend to decline across the grades, unless schools and teachers work to develop and implement appropriate practices of partnership at each grade level.”

- “Affluent communities currently have more positive family involvement, on average, unless schools and teachers in economically distressed communities work to build positive partnerships with their students’ families.”

- “Schools in more economically depressed communities make more contacts with families about the problems and difficulties their children are having, unless they work at developing balanced partnership programs that also include contacts about the positive accomplishments of students.”

- “Single parents, parents who are employed outside the home, parents who live far from the school, and fathers are less involved, on average, at the school building, unless the school organizes opportunities for families to volunteer at various times and in various places to support the school and their children.”

As the summary above illustrates, predictable patterns of school, family, and community disconnection will result unless educators, students, families, and community members take affirmative, proactive steps to address negative overlapping influences and build positive, mutually beneficial partnerships. That’s where the Framework of Six Types of Involvement comes in.

The Framework of Six Types of Involvement

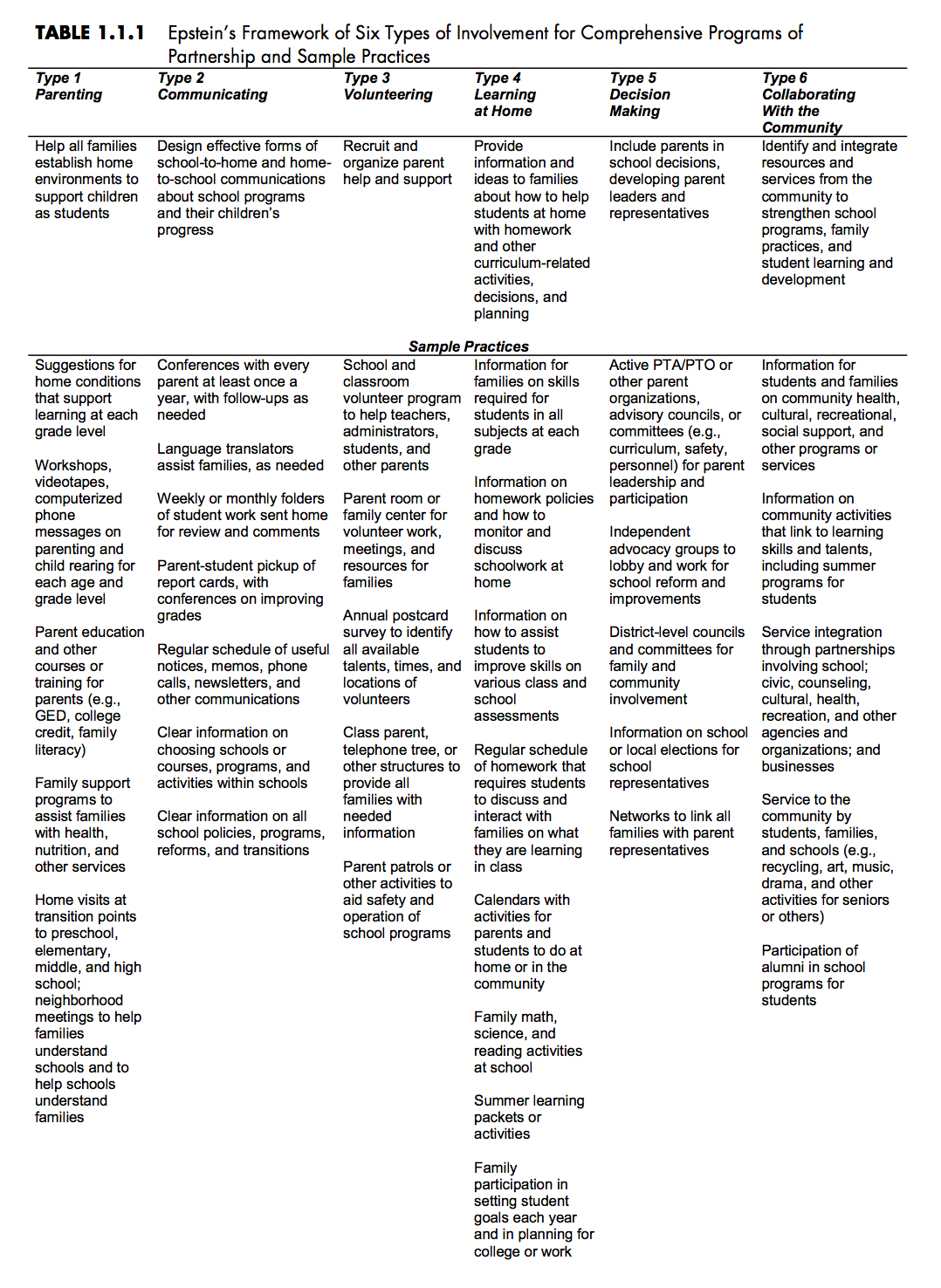

The full technical name of Epstein’s framework is the Framework of Six Types of Involvement for Comprehensive Programs of Partnership and Sample Practices. When discussing the framework, Epstein and her collaborators emphasize that each type of involvement is a two-way partnership—and ideally a partnership that is co-developed by educators and families working together—not a one-way opportunity that has been unilaterally determined by a school.

The six types of involvement are:

- Parenting: Type 1 involvement occurs when family practices and home environments support “children as students” and when schools understand their children’s families.

- Communicating: Type 2 involvement occurs when educators, students, and families “design effective forms of school-to-home and home-to-school communications.”

- Volunteering: Type 3 involvement occurs when educators, students, and families “recruit and organize parent help and support” and count parents as an audience for student activities.

- Learning at Home: Type 4 involvement occurs when information, ideas, or training are provided to educate families about how they can “help students at home with homework and other curriculum-related activities, decisions, and planning.”

- Decision Making: Type 5 involvement occurs when schools “include parents in school decisions” and “develop parent leaders and representatives.”

- Collaborating with the Community: Type 6 involvement occurs when community services, resources, and partners are integrated into the educational process to “strengthen school programs, family practices, and student learning and development.”

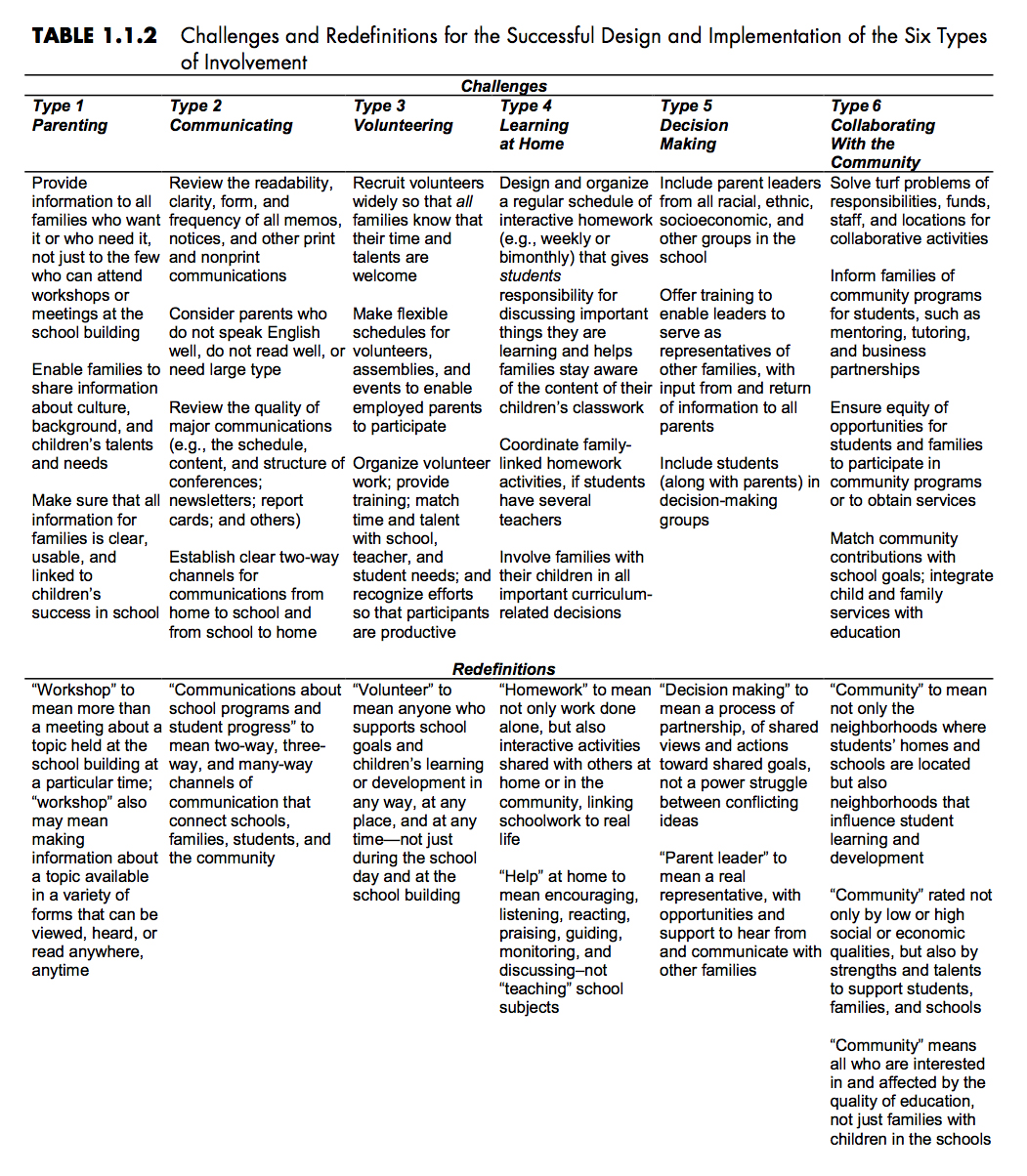

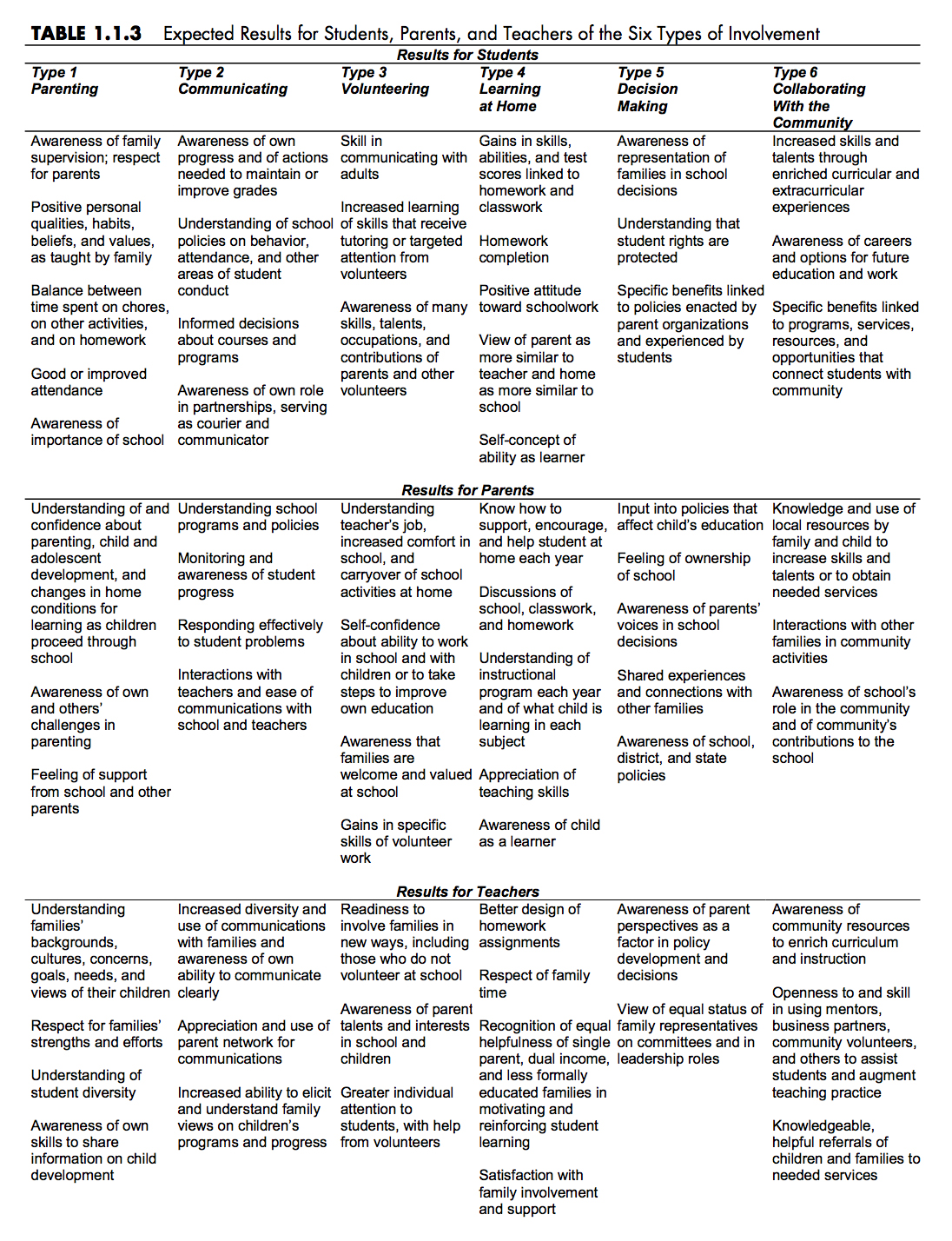

What distinguishes Epstein’s framework from many similar frameworks is the extensive lists of descriptive examples that Epstein provides to illustrate how each type of involvement works in real-life settings. Rather than relying on an abstract metaphorical presentation (such as a Venn diagram) to explain the model, Epstein and her colleagues developed a set of three comprehensive tables:

1. The first table describes the six types of involvement above and provides an attendant set of representative practices and strategies:

2. The second table—entitled Challenges and Redefinitions for the Successful Design and Implementation of the Six Types of Involvement—presents a set of “challenges” to forms of involvement (i.e., alternative methods and problems that will need to be solved), as well as redefinitions of conventional terms such as workshop, volunteer, or community:

3. The third table—entitled Expected Results for Students, Parents, and Teachers of the Six Types of Involvement—provides descriptions of representative outcomes of the six types of involvement for students, parents, and teachers:

While the Framework of Six Types of Involvement provides a level of detailed description absent from similar models, Epstein addresses a few limitations of the framework. For example, Epstein writes, “The tables cannot show the connections that occur when one practice activates several types of involvement simultaneously.” The tables are useful because they provide simplified, well-organized presentations of complex social and organizational dynamics, but like all simplifying models the tables cannot take into account every factor that may positively or negatively impact different forms of involvement and school-family-community partnership, including the myriad cultural dynamics at play in any given school or community.

Epstein also points out that the tables “simplify the complex longitudinal influences that produce various results over time.” Even the best-designed programs can produce poor results for reasons that may be elusive to those involved. And as time goes on, and the conditions of any given program or approach evolve, the parsing of positive and negative influences and causes may be even more difficult to isolate and identify.

For example, the tables do not directly address larger questions, such as disproportionality in school-family-community power; the harmful effects of influences such as institutionalized bias, discrimination, and racism; or strategies such as community organizing and protest that aim to wrest some degree of power away from institutions that may be reluctant or unwilling to share power or partner in authentic ways with students and families. One of the hazards of omitting frank discussions of power, privilege, or prejudice, for example, is that people may start doing the right things, but they may do them for the wrong reasons, which can result in new programs that merely reproduce the same problems, conflicts, discrimination, or inequitable results as the old programs.

Summarizing the options available to school, family, and community partners, Epstein provides readers with the following consideration:

“Schools have choices. There are two common approaches to involving families in schools and in their children’s education. One approach emphasizes conflict and views the school as a battleground. The conditions and relationships in this kind of environment guarantee power struggles and disharmony. The other approach emphasizes partnership and views the school as a homeland. The conditions and relationships in this kind of environment invite power-sharing and mutual respect, and allow energies to be directed toward activities that foster student learning and development. Even when conflicts rage, however, peace must be restored sooner or later, and the partners in children’s education must work together.”

Acknowledgments

Organizing Engagement thanks Joyce Epstein for her contributions to improving this resource and for permission to reproduce images from School, Family, and Community Partnerships: Your Handbook for Action (Third Edition).

References

Epstein, J. L., et al. (2019). School, Family, and Community Partnerships: Your Handbook for Action. Fourth edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Epstein, J. L. (May 1995). School/family/community partnerships: Caring for the children we share. Phi Delta Kappan, 76(9), 701–712.

Creative Commons

This work by Organizing Engagement is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. When excerpting, adapting, or republishing content from this resource, users should cite the source texts and confirm that all quotations and excerpts are accurately presented.