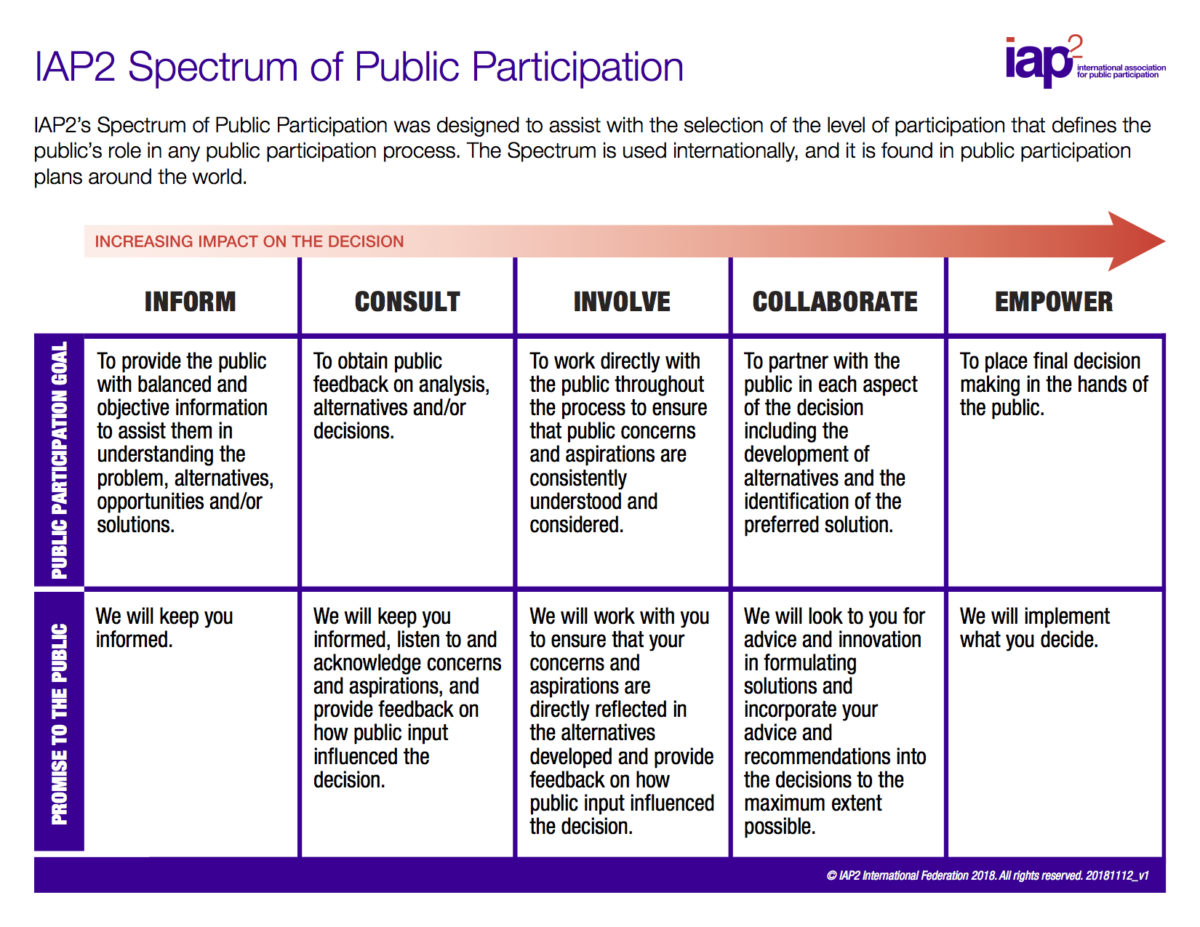

Developed by the International Association for Public Participation (IAP2)—an international professional organization that works to advance the practice of public participation globally—the influential Spectrum of Public Participation has been widely used and adapted by practitioners since it was first proposed in the early 2000s.

The Spectrum of Public Participation is based on decades of research and practice in the field of public participation, and shares similarities with other models, notably the Ladder of Citizen Participation, Ladder of Children’s Participation, Ladder of Empowerment, Typology of Youth Participation and Empowerment Pyramid, and Youth Engagement Continuum, among others.

“Engagement professionals require professional agility and intellectual flexibility to adapt to the specific (and often specialist) nature of varying projects, and recognise that community and stakeholder roles will also alter depending on the required level of engagement in engagement. To respond to this special consideration IAP2 has developed the Public Participation Spectrum that is designed to assist with the level of influence that is required, depending on the community or stakeholder’s role in the engagement.”

Quality Assurance Standard for Community and Stakeholder Engagement, International Association for Public Participation

The model is also informed by the work of IAP2’s international network of affiliates and public-participation professionals, and it reflects the organization’s Code of Ethics and Core Values for the Practice of Public Participation:

- Public participation is based on the belief that those who are affected by a decision have a right to be involved in the decision-making process.

- Public participation includes the promise that the public’s contribution will influence the decision.

- Public participation promotes sustainable decisions by recognizing and communicating the needs and interests of all participants, including decision-makers.

- Public participation seeks out and facilitates the involvement of those potentially affected by or interested in a decision.

- Public participation seeks input from participants in designing how they participate.

- Public participation provides participants with the information they need to participate in a meaningful way.

- Public participation communicates to participants how their input affected the decision.

The Public Participation Spectrum

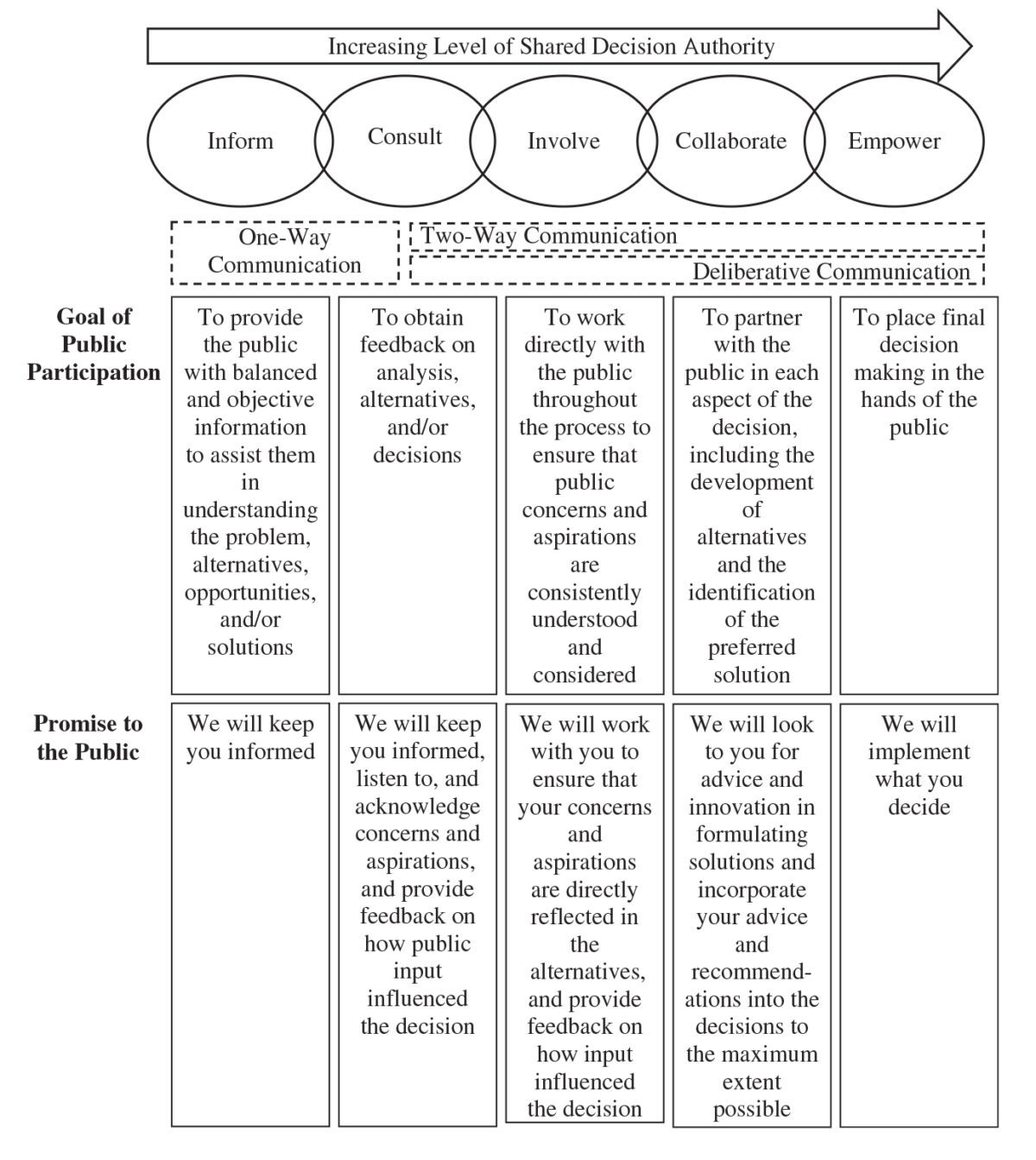

Due to its simplicity and descriptiveness, the Spectrum of Public Participation is particularly useful for those who are new to civic engagement and participation. The framework was developed to “help groups define the public’s role in any public participation process,” and therefore it can be applied in diverse engagement processes and contexts. Presented in a table format, the spectrum describes five general modes of public participation that fall on a progressive continuum of increasing influence over decision-making in a given civic-engagement process. Importantly, the model not only describes the goals of a given mode of public participation, but also the “promise” that each mode communicates—whether implicitly or explicitly—to the public.

Readers should note, however, that the Spectrum of Public Participation presents only a positive view of public participation at its most constructive, meaning that it does not consider ineffective, inauthentic, or deficient participatory practice—i.e., how a particular “promise” to the public may be broken or what consequences may result. For this reason, a brief discussion of negative forms of public participation has been included below to help readers understand both the beneficial and harmful applications of public participation.

The five modes of public participation:

1. Inform

The goal of an informing process is to “provide the public with balanced and objective information to assist them in understanding the problem, alternatives, opportunities, and/or solutions.” In an informing process, participants are largely passive recipients of information, though they may use the information they receive at a later time (e.g., when considering how to vote on a referendum issue or whether to become involved in a participatory process). At its most effective and beneficial, the information shared with the public is as objective, accurate, and fact-based as possible, and an informing process keeps the public apprised of the rationales motivating the decisions being made by leaders such as school administrators, public officials, or elected representatives.

An informing process can become problematic, however, when leaders are not fully transparent and withhold important or essential information, or when they provide biased information for the purposes of misrepresenting an issue and manipulating public perception. In its most potentially harmful manifestation, an informing process can be used as a manipulative tactic for mollifying legitimate public concerns or deceiving the public into supporting a decision or policy that is not in their interest.

2. Consult

The goal of a consulting process is to “obtain public feedback on analysis, alternatives, and/or decisions.” In a consulting process, participants contribute their viewpoints, opinions, or preferences, and leaders then use this information to inform their decisions. At its most effective and beneficial, a consulting process improves the outcomes of a decision-making process by giving public officials or school administrators a more accurate understanding of the beliefs, needs, concerns, or priorities of those who will be impacted by their decisions.

A consulting process can become problematic, though, when leaders collect public feedback but do not take it into consideration, or when they leave important constituencies or stakeholder groups—such as youth or communities of color—out of the process. At its most harmful, a disorganized consulting process can take up a large amount of the public’s time or resources, but produce few tangible results, or it can be manipulatively designed to make the public feel it has been heard, when in fact leaders ignore (or perhaps never intended to act on) the public’s recommendations. When consulting processes are inauthentic or unproductive, they can undermine public trust and confidence in a decision-making process or in public institutions generally.

3. Involve

The goal of an involving process is to “work directly with the public throughout the process to ensure that public concerns and aspirations are consistently understood and considered.” In an involving process, participants are actively involved in a decision-making process organized by leaders such as school administrators and public officials. At its most effective and beneficial, an involving process includes members of the public in meaningful roles (e.g., by training them to be facilitators or giving them some degree of leadership authority, such as chairing a committee), and the public is included from the beginning stages of the process (e.g., during the identification of a problem and the development of a proposed process to tackle the problem) through its conclusion (e.g., reflecting on the process—what worked well, what didn’t work well—and evaluating the outcomes of the final decision).

An involving process can become problematic, however, when leaders and organizers do not provide the training, education, encouragement, or other forms of support that public participants may need to fully or competently participate, or when the opportunities provided for public involvement are inauthentic—e.g., when leaders are “forced” by policy to involve the public in a decision-making process, and then they merely go through the motions for the purpose of compliance, or when leaders unilaterally overrule participant decisions they disagree with. At its most harmful, an involving process can be intentionally and selectively exclusionary for the purpose of empowering some members, groups, or viewpoints over others, or it can be so mismanaged, disingenuous, or even fraudulent that the public begins to distrust those in leadership positions, lose faith in their public institutions, or question whether any participatory process can be genuine.

4. Collaborate

The goal of a collaborative process is to “partner with the public in each aspect of the decision including the development of alternatives and the identification of the preferred solution.” In a collaborative process, leaders such as school administrators and public officials work in partnership with members of the public to identify problems and develop solutions. At its most effective and beneficial, genuine collaborative processes and partnerships give leaders and participants equal status, and those who hold the power share some degree of control, management, or decision-making authority with participants.

A collaborative process can become problematic or harmful, however, when leaders use their position, authority, influence, or power to exploit or disempower their partners. For example, leaders may take advantage of partner’s network of supporters to win an election or vote, but then refuse to the honor promises they made during the campaign, or leaders may ask partners to do most of the work on a project while the leaders derive most of the benefits, funding, or accolades.

5. Empower

The goal of an empowering process is to “place final decision making in the hands of the public.” In an empowering process, leaders such as school administrators and public officials may partially or entirely turn over control, management, or decision-making authority to public participants, or the public may mobilize to develop a decision-making process in lieu of institutional leadership or action on an important issue. At its most effective and beneficial, an empowering process entrusts the public with decision-making authority, and thereby builds greater trust among the public, and it provides the necessary resources (e.g., political education, social connections, training, funding, interpreters, transportation, etc.) to members of the public who may be disadvantaged or unable to participate without accommodations or assistance.

An empowering process can become problematic or harmful, however, when organizations or individuals are entrusted to manage a process they may not have the capacity or resources to manage competently, or when institutional leaders, professionals, and experts remove themselves from a decision-making or problem-solving process that requires institutional leadership, specialized expertise, or professional skills to achieve a successful conclusion or resolution. While “empowerment” is often represented as the apex of public participation in models such as the Public Participation Spectrum, many academics, researchers, and practitioners have advised against viewing empowerment, or any other mode of participation or engagement, as universally or unequivocally good, given that all modes of participation entail both compromises and potentially abuses—as the above examples of negative forms of participation illustrate.

Acknowledgments

Organizing Engagement thanks Ellen Ernst for her contributions to improving this introduction, and the International Association for Public Participation for permission to reproduce excerpts and images from its publications.

References

International Association for Public Participation Australasia. (2016). Quality Assurance Standard for Community and Stakeholder Engagement. Victoria, Australia.

Nabatchi, T. (2012). Putting the public back in public values research: Designing participation to identify and respond to values. Public Administration Review, 72(5), 699–708.

Creative Commons

This work by Organizing Engagement is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. When excerpting, adapting, or republishing content from this resource, users should cite the source texts and confirm that all quotations and excerpts are accurately presented.