Proposed by Archon Fung in his influential 2006 Public Administration Review article “Varieties of Participation in Complex Governance,” the Varieties of Participation model describes different forms of public participation in governmental policy-making and decision-making. While Fung’s model has national-level application, he focuses his analysis on the functioning of local (e.g., municipal or educational) governments and institutions.

“If the best reason for public participation is the one that John Dewey gave—that the man who wears the shoe, not the shoemaker, knows best where it pinches—then participants need to do more than complain to policy makers.”

Archon Fung, Varieties of Participation in Complex Governance

In his article, Fung explains his reasons for developing the model:

“The multiplex conditions of modern governance demand a theory and institutions of public participation that are appropriately complex in at least three ways. First, unlike the small New England town or even the Athenian city-state, there is no canonical form of direct participation in modern democratic governance; modes of contemporary participation are, and should be, legion. Second, public participation advances multiple purposes and values in contemporary governance. Master principles such as equal influence over collective decisions and respect for individual autonomy are too abstract to offer useful guidance regarding the aims and character of citizen participation. It is more fruitful to examine the range of proximate values that mechanisms of participation might advance and the problems they seek to advance…. Third, mechanisms of direct participation are not (as commonly imagined) a strict alternative to political representation or expertise but instead complement them. As we shall see, public participation at its best operates in synergy with representation and administration to yield more desirable practices and outcomes of collective decision making and action [emphasis added].”

Fung’s final line above offers a particularly useful insight for those working in the fields of education organizing, engagement, and equity: student, family, and community participation in school governance and decision-making works best when participatory activities operate in synergy with the administration of schools. In many districts, schools, and communities, local leaders view organizing and engagement as an either/or trade-off: either school administrators are making the decisions without community participation or school administrators are handing over control and authority to community members. Either the educational experts are right and should therefore decide, or the parents are right and the educators should do what they say.

Even more common, however, it’s the fear—not necessarily the reality—that student, family, and community participation in school decision-making will inevitably result in the displacement or replacement of administrative authority, a fear that often leads many school administrators to be skeptical of or even hostile to the prospect of greater community participation in school governance.

For this reason, Fung’s model offers a useful framework for local leaders who are considering increasing community involvement in school governance and decision-making. By articulating the different forms of participation available, and some of the characteristics of each form, the Varieties of Participation model can help local leaders and participants move toward and adopt more synergistic—rather than oppositional or confrontational—varieties of participation.

Fung concludes his article with a discussion of the three foundational values of legitimacy, justice, and effectiveness in democratic processes and institutions.

The Varieties of Participation Model

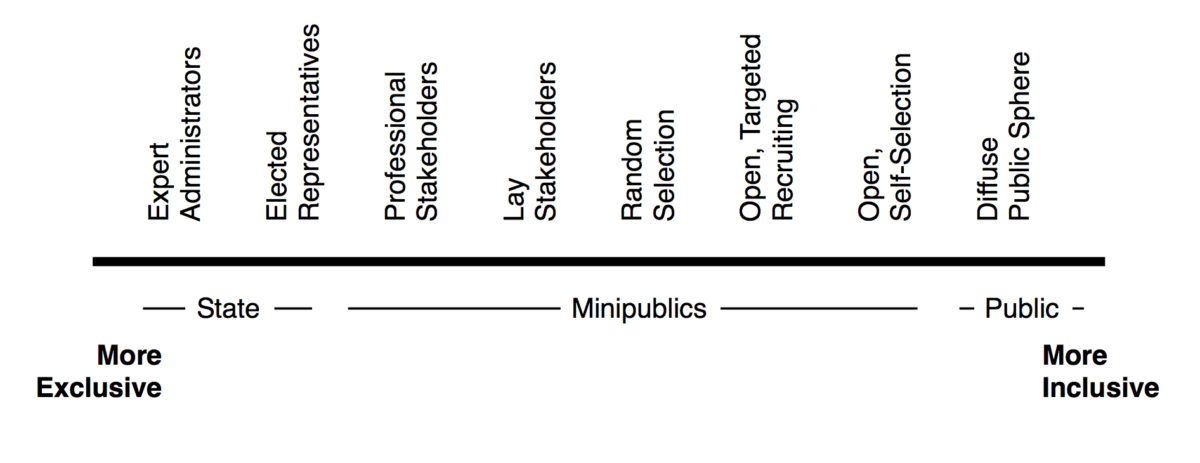

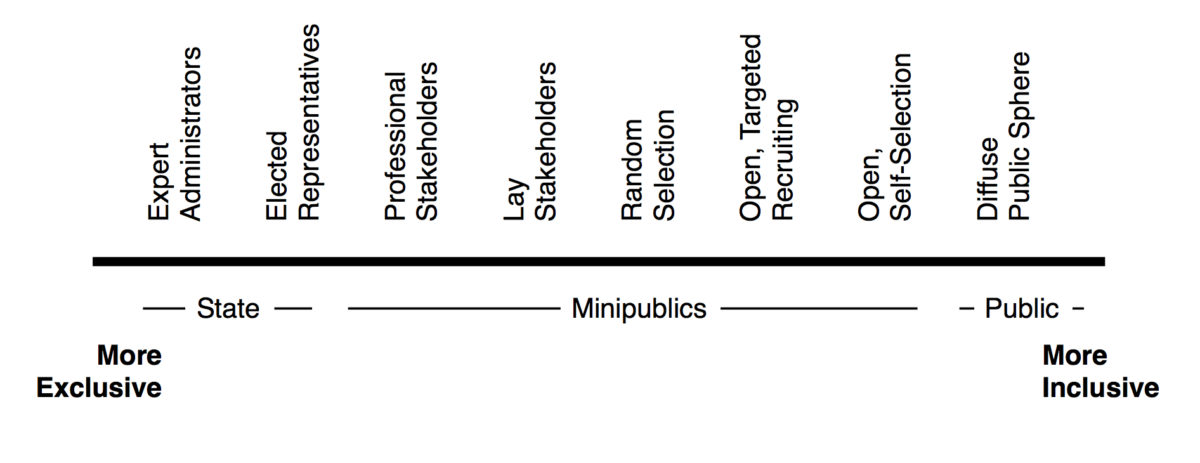

Fung’s Varieties of Participation model is presented as three continuums describing (1) the methods of participatory selection, (2) the modes of communication and decision-making provided to the public, and (3) the degrees of power and authority granted to public participants. These three continuums are then formulated into a three-dimensional model—what Fung calls the “democracy cube”—in which “varieties of participatory mechanism can be located and contrasted.”

Fung’s model primarily describes varieties of “institutional design,” meaning the ways in which institutions (governments, agencies, municipalities, schools, nonprofits, associations, etc.) are typically either designed for participation or design processes of participation.

Methods of Participant Selection

Fung describes the standard methods by which the public is selected for participation in governance, and the relative degree of exclusion and inclusion that attends each form of participant selection. On the left-hand side of the participant-selection continuum, the professional administrators hired to manage districts, schools, or governmental agencies represent the most exclusive form of participation, while the “diffuse public sphere,” which encompasses participation in everything from social-media commentary to town-square demonstrations, represents the most inclusive form of participation and governmental influence available to the public.

The continuum also tracks with general levels of influence in government. For example, administrators and elected officials typically have the most amount of direct influence in governance, while those commenting on Twitter or holding signs during protests typically have the least amount of direct influence.

The eight methods of participant selection:

- Expert Administrators: This variety of participation is limited to individuals who manage government agencies, institutions, and programs, and therefore it is the most exclusive. Participation requires specialized credentials or years of experience, and it is limited to those who are employed by governmental agencies.

- Elected Representatives: This variety of participation is limited to individuals who hold elected office, and therefore participation requires, for example, a successful electoral campaign and the financial backing required to fund such a campaign.

- Professional Stakeholders: This variety of participation is limited to individuals who are paid to be involved in governance (e.g., lobbyists, consultants, campaign directors, union representatives, the executive directors of professional associations, etc.), and therefore participation requires professional expertise and connections.

- Lay Stakeholders: This variety of participation is limited to “unpaid citizens who have a deep interest in some public concern” and “who are willing to represent and serve those who have similar interests and perspectives but choose not to participate,” and therefore participation requires lay stakeholders to possess requisite personal resources, such as money, disposable time, political education, or confidence.

- Random Selection: This variety of participation is limited to individuals who are randomly selected to participate in governance, and therefore participation requires selection through a randomized process. Examples include polls, such as voter opinion polls; focus groups, such as those conducted by campaign strategists to determine how typical voters in a target demographic view a particular issue; and juries, such as “citizen juries” in which randomly selected samples of residents or voters are recruited to participate in a deliberative process on a political issue or governmental decision.

- Open, Targeted Recruiting: This variety of participation is limited to individuals who are selectively recruited to participate in governance, and therefore participation requires recruitment, whether it results from an active-recruitment process conducted by public officials, government leaders, administrators, organizers, or strategists, or a passive-recruitment process that incentivizes certain people to participate more than others. According to Fung, an example of active targeted recruitment might take the form of community organizers inviting people in a low-income community to attend a meeting on a proposed housing development, while an example of passive targeted recruitment would might take the form of a subset of citizens with strong ideological viewpoints or special interests—e.g., senior residents and voters concerned about increasing property taxes—attending a town hall or public meeting in larger numbers (thereby achieving a majority voice and level of influence) due to their greater personal investment in the topic and outcome. While the participatory process may be “open” to everyone, both the active and passive forms of recruitment result in a selective—but not exclusive or exclusionary—participation process.

- Open, Self-Selection: This variety of participation is open to anyone who would like to participate, and therefore participation requires only interest, willingness, availability, and whatever other basic resources are needed to participate (e.g., transportation, childcare, an ability to understand the language being used, etc.). While this form of participation is the least restrictive, and therefore potentially the most inclusive, Fung offers the following caution: “Though complete openness has an obvious appeal, those who choose to participate are frequently quite unrepresentative of any larger public. Individuals who are wealthier and better educated tend to participate more than those who lack these advantages, as do those who have special interests or stronger views.”

- Diffuse Public Sphere: This variety of participation is a form of self-selection open to anyone who would like to participate, but the barriers to participation are lower, as is the likely level of influence over governmental policy and decision-making. While a town-hall meeting or a legislative public-comment process would represent forms of open self-selection, individual political protests conducted either online or in a public square would represent forms of self-selection in the diffuse public sphere.

Modes of Communication and Decision

Fung describes the standard modes of communication and decision-making in governance, and the relative degree of intensity that attends each mode. On the left-hand side of the continuum, participation takes the form of passive observation and listening; on the right-hand side of the continuum, participation takes the form of tactical maneuvers deployed by experts and professionals.

Like the methods of participant selection, the continuum tracks with general levels of influence—i.e., passive listeners tend to have less influence that veteran political strategists and insiders who can manipulate governmental policy-making from behind the scenes. As Fung notes, the first three modes “do not attempt to translate the views or preferences into a collective view or preference,” whereas the second three attempt to do so in a variety of different ways.

The six modes of communication and decision-making:

- Listen as Spectator: This mode of communication and decision-making is the most common, given that “the vast majority of those who attend events such as public hearings and community meetings do not put forward their own views at all.” While during the process of listening spectators may gain information that they can use later on (e.g., when voting), this mode of participation is largely passive, and the participants “bear witness to struggles among politicians, activists, and interest groups.”

- Express Preferences: This mode of communication and decision-making occurs when participants express their opinions, beliefs, and preferences in a public forum, such as when residents stand up at a town-hall or school-board meeting to testify in support of a particular local policy proposal. While participants may express their views in these contexts, public officials and administrators are typically under no obligation to act on the preferences expressed by participants.

- Develop Preferences: This mode of communication and decision-making occurs when participants are given opportunities to “explore, develop, and perhaps transform their preferences and perspectives,” according to Fung. Processes that allow participants to develop preferences “encourage participants to learn about issues and, if appropriate, transform their views and opinions by providing them with educational materials or briefings and asking them to consider the merits and trade-offs of several alternatives.” In these cases, participants deliberate, question, and reason, rather than simply accept the views, preferences, or decisions of experts, advocates, politicians, or public officials.

- Aggregate and Bargain: This mode of communication and decision-making occurs when participants aggregate their preferences (e.g., through a majority-vote process) or bargain with one another (e.g., through a public debate) to reach a decision or compromise. As Fung notes, aggregation and bargaining processes can be “mediated by the influence and power” of different participants, meaning that more influential or powerful figures such as elected officials or public administrators can set the terms of the debate or manipulate the process to their advantage, which can result in the marginalization or disenfranchisement of some community groups and participants.

- Deliberate and Negotiate: This mode of communication and decision-making occurs when participants engage in a process of deliberation and negotiation to determine what they want as individuals or as a group. As Fung describes, “In mechanisms designed to create deliberation, participants typically absorb educational background materials and exchange perspectives, experiences, and reasons with one another to develop their views.” Fung identifies two features that distinguish deliberation and negotiation from other modes: “First, a process of interaction, exchange, and—it is hoped—edification precedes any group choice. Second, participants in deliberation aim toward agreement with one another (though frequently they do not reach consensus) based on reasons, arguments, and principles.”

- Deploy Technique and Expertise: This mode of communication and decision-making is executed by experts, strategists, and other professionals (e.g., regulators, urban planners, social workers, police officers, school administrators, teachers, etc.), and it typically excludes citizens, residents, youth, and other members of the lay public. While many forms of technical participatory governance are beneficial given that specialized training and expertise is often required to solve public problems (such as regulating businesses appropriately, evaluating potential public contractors, educating children, etc.), the absence of robust public participation—and the accountability and transparency that such participation brings—may render decision-making by experts more susceptible to influence peddling, graft, corruption, and other factors that can subvert the public interest.

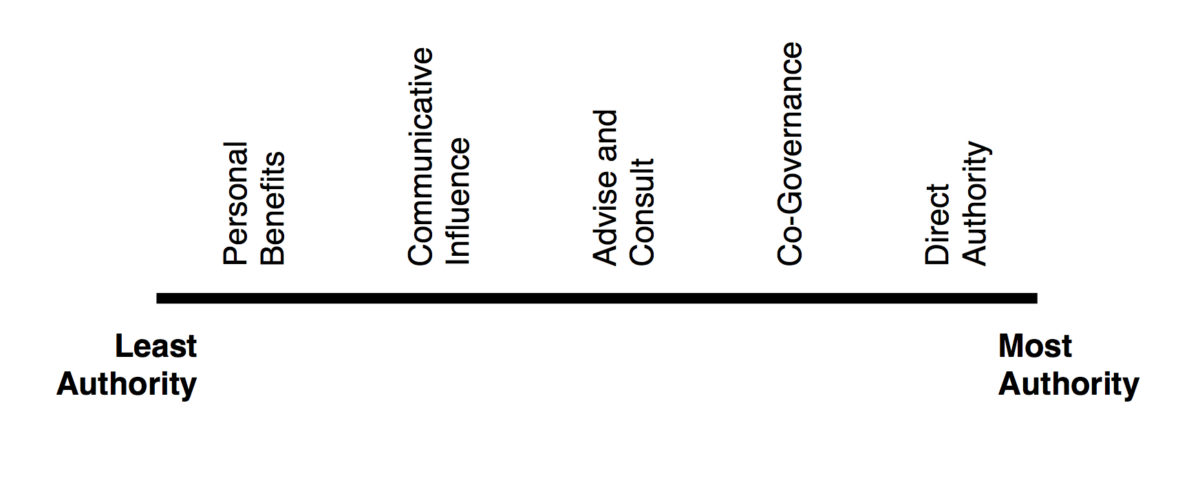

Forms of Authority and Power

Fung describes the standard modes of authority and power in governance, and the relative degree of influence that attends each form. On the left-hand side of the continuum, personal benefits from governmental decisions represent the least authority; on the right-hand side of the continuum, the direct exercise of power represents the greatest authority. Like the preceding methods and modes, the continuum also describes general levels of participant influence in governmental processes.

The five forms of participant authority and power:

- Personal Benefits: As Fung points out, “In many (perhaps most) participatory venues, the typical participant has little or no expectation of influencing policy or action. Instead, he or she participates to derive personal benefits of edification or perhaps fulfill a sense of civic obligation.” In this form, people participate for reasons of personal principle or fulfillment, and therefore their potential influence in a process may be either irrelevant (to the participant) or negligible (within the process).

- Communicative Influence: This form of influence occurs, according to Fung, when “participatory mechanisms exert influence on the state or its agents indirectly by altering or mobilizing public opinion.” Communicative influence occurs when officials holding government office or managing public agencies and institutions are swayed by public testimony, advocacy, debates, or protests, whether it takes the form of an organized advocacy campaign or the public backlash that can follow a well-publicized incident of prejudice or corruption.

- Advise and Consult: This form of influence occurs when “officials preserve their authority and power but commit themselves to receiving input from participants,” writes Fung. Public hearings, town-hall forums, and open school-board meetings are generally considered opportunities for the public to “advise and consult” with public officials (although, of course, in many of these forums public officials often decline to consult the public in an authentic way or take what the public says under advisement).

- Co-Governance: This form of influence occurs, according to Fung, when members of the public “join with officials to make plans or policies or to develop strategies for action.” Fung provides an example from the public school system in Chicago: the schools are governed by administrators working in collaboration with a “Local School Council” composed of parents and community members.

- Direct Authority: This form of influence occurs when public participants exert direct authority or control over a governing process, such as in the classic case of the New England town meeting that turns policy-making over to local residents.

References

Fung, A. (December 2006). Varieties of participation in complex governance. Public Administration Review, 66–75.

Creative Commons

This work by Organizing Engagement is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. When excerpting, adapting, or republishing content from this resource, users should cite the source texts and confirm that all quotations and excerpts are accurately presented.