The Storytelling Project Model was developed by Lee Anne Bell, a professor of education at Barnard College who has taught and facilitated numerous courses, workshops, and dialogues on race and racism over her four-decade career. In 2004–2005, Bell collaborated with a team of public-school teachers, academics, artists, and university students to pilot an anti-racist storytelling project in New York City that provided the model’s foundational design and insights.

The Storytelling Project Model is grounded in an extensive body of academic research, but it was also informed by the knowledge, expertise, and lived experiences of Bell’s many collaborators.

The Storytelling Project Model is described in Storytelling for Social Justice: Connecting Narrative and the Arts in Antiracist Teaching, which was originally published in 2010. A second edition of the book was released in 2019. Bell and her collaborators also developed a companion curriculum that is freely available for download.

The purpose of the Storytelling Project Model is to help communities “discover, develop, and analyze stories about racism that can catalyze consciousness and commitment to action.” While the model was originally developed for use with students in instructional contexts, it has been adapted for application in a wide variety of dialogue processes with adults and youth.

The model offers a framework that local leaders, facilitators, and organizers can use to explore “how racial stories and storytelling both reproduce and challenge the racial status quo, and how methods derived from storytelling and the arts might help us expose and constructively analyze pervasive patterns that perpetuate racism in daily life.” The final chapter of Storytelling for Social Justice—“Cultivating a Counter-Storytelling Community: The Storytelling Project Model in Action”—describes a step-by-step process for applying the model in schools and communities.

“As we link our individual stories into a collective story we discern patterns of racism. We see how dominance and subordination are engendered, even against our own desires. We witness how our stories are interconnected, how advantage and disadvantage are constructed. It becomes impossible for a white person to say, ‘I never owned slaves, so I’m not responsible for the aftermath.’ We come to know in our guts that we are responsible and must be responsive to what our collective history has wrought if we are ever to be truly free in the present.

Lee Anne Bell, Storytelling for Social Justice: Connecting Narrative and the Arts in Antiracist Teaching

We experience at a visceral level how everyone, regardless of race, is dehumanized, albeit in racially specific ways, through socialization in a racialized system. Such deep recognition creates the conditions for engaging more consciously with difference, recognizing the individual and collective work necessary to develop commitments to challenge these patterns in our institutions and personal lives. Through exercises such as this we (re)discover concealed stories about how racial consciousness is shaped and transmitted from within families and communities, but linked to patterns in the larger society that transcend individual experience.”

In Storytelling for Social Justice, Bell explains why she and her collaborators developed the model:

“Central to the Storytelling Project Model is our belief that a properly supportive counter-storytelling community must be intentionally created to bear witness to and support ‘the naming of trauma and the grief, rage, and defiance that follow’ [Aurora Levins Morales, Medicine Stories: History, Culture, and the Politics of Integrity]. Within an intentional storytelling community, people from different racial locations relate their own and hear other’s stories, working together to make connections that are hidden by the dominant narratives about racial life. Using written and performance exercises, interviews, dialogues, and discussions with people from one’s own racial group and with others from across racial groups, we evoke experiences with race and racism as a basis for revealing the patterns that connect.”

Read the Organizing Engagement interview with Lee Anne Bell, author of Storytelling for Social Justice: Connecting Narrative and the Arts in Antiracist Teaching →

Concepts for Understanding Race and Racism

In Storytelling for Social Justice, Bell describes four foundational concepts that inform the Storytelling Project Model:

1. Race is a social construction

The perception of different human “races” is not a biological fact, but an illusion that is manufactured by cultural assumptions, biases, and influences. All human groups are biologically and genetically similar, and there is more variation in human characteristics within any particular racial group than there is between groups. Yet the concept of race indelibly shapes the lived experiences of people in powerful ways by advantaging some groups and disadvantaging others. According to Bell, even though race is “constructed through ideas and language, rather than biology,” it still has “significant material consequences in the real world.”

2. Racism is a system that operates on multiple levels

Racism is most usefully understood as a system of social norms, behaviors, and power dynamics that operate at every level of society, not as isolated acts of racial prejudice committed by individuals. As Bell writes, racism “shapes our government, schools, churches, businesses, media, and other social institutions in multiple and complex ways that serve to reinforce, sustain, and continually reproduce an unequal status quo.” It is “a system that has been in place for centuries” and it “often operates outside of consciousness or deliberate intention.”

3. White supremacy and white privilege are neglected aspects of systemic racism

The concept of race can determine “access to resources and life possibilities in ways that benefit the white racial group at the expense of groups of color,” writes Bell, and seeing “whiteness as a central feature in the study of racism enables us to identify the power dynamics and unearned advantages that accrue to whites as a group.” For example, the dominant beliefs and social customs that are perceived as “normal” in society usually reflect white concerns, interests, and priorities. If these conventions are then routinely and unconsciously used to make judgments about individuals or groups, those judgments will disproportionately be biased in favor of whites.

4. The ideal of “color-blindness” is a barrier to racial progress

The common but naive perception that it is better to “not see” skin color or racial difference can shut down honest conversations about race. When race is routinely ignored or avoided in social, organizational, and political discourse, it plays a role in perpetuating racial inequality by allowing the status quo to persist unchallenged. To achieve racial progress, Bell writes, people must “surface stories that illustrate racism’s differential effects on white people and people of color so as to challenge color-blindness and generate more grounded and informed dialogue about racial realities.”

The Storytelling Project Model

The Storytelling Project Model can be used by local leaders, educators, facilitators, and organizers who want to host constructive dialogues on race in their schools and communities. The model utilizes different forms of narrative—such as personal stories, literature, poetry, visual arts, or dramatic performances—to convey the lived experiences of race in revealing ways, and to help participants understand and collectively analyze the many forms that racism can take in social interactions, cultural norms, institutional policies, political discourse, or the media.

For example, Bell discusses how the documentary film Race: The Power of an Illusion “shows the power of images and stories to name and challenge erroneous but popularly accepted (stock) stories about race” and “how race and white privilege have been constructed through law, government policy, and social practice.” Bell also produced a documentary Forty Years Later: Now Can We Talk? (2013), that can be used to engage groups in honest and potentially transformative dialogues on race and racism. The film tells the stories of the first class of African Americans to integrate their high school in the Mississippi Delta in 1967–1969. A companion discussion guide is also available.

In Storytelling for Social Justice, Bell describes the reasons why the model uses stories, and the storytelling process, to explore race and racism:

- “Stories are one of the most powerful and personal ways that we learn about the world, passed down from generation to generation through the family and cultural groups to which we belong. As human beings, we are primed to engage each other and the world through language, and stories can be deeply evocative sources of knowledge and awareness.”

- “Storytelling and oral tradition are also democratic, freely available to all, requiring neither wealth and status nor formal education. Indeed, stories have historically provided ways for people with few material resources to maintain their values and sense of community in the face of forces that would disparage and attempt to destroy them.”

- “Because stories operate at both individual and collective levels, they can bridge the sociological/abstract with the psychological/personal contours of daily experience. They help us connect individual experiences with systemic analysis, allowing us to unpack, in ways that are perhaps more accessible than abstract analysis alone, racism’s hold on us as we move through the institutions and cultural practices that sustain racism.”

- “Further, because stories carry within them historical/social formations and sedimented ways of thinking…stories offer an accessible vehicle for uncovering normative patterns and historical relations that perpetuate racial privilege. They also potentially enable conscious development of new stories that contest the racial status quo and offer alternative visions for democratic and socially just relations.”

In Storytelling for Social Justice, Bell also discusses ground rules and facilitation strategies for small-group conversations that utilize the Storytelling Project Model, including a set of guiding questions that were adapted from the discussion guide for Race: The Power of an Illusion:

- What is the difference between a biological and social view of race? How have biological assumptions about race become taken for granted “common knowledge”? How might these assumptions be challenged?

- How has whiteness been defined historically? What purposes have changing definitions of whiteness served in American society? To whose benefit?

- Why do the stories we tell about race matter? What purposes do they serve? How do we negotiate the fallacy of biological race with the reality of race as lived experience?

- What stories are erased, trivialized, or concealed by the dominant story? How does this happen?

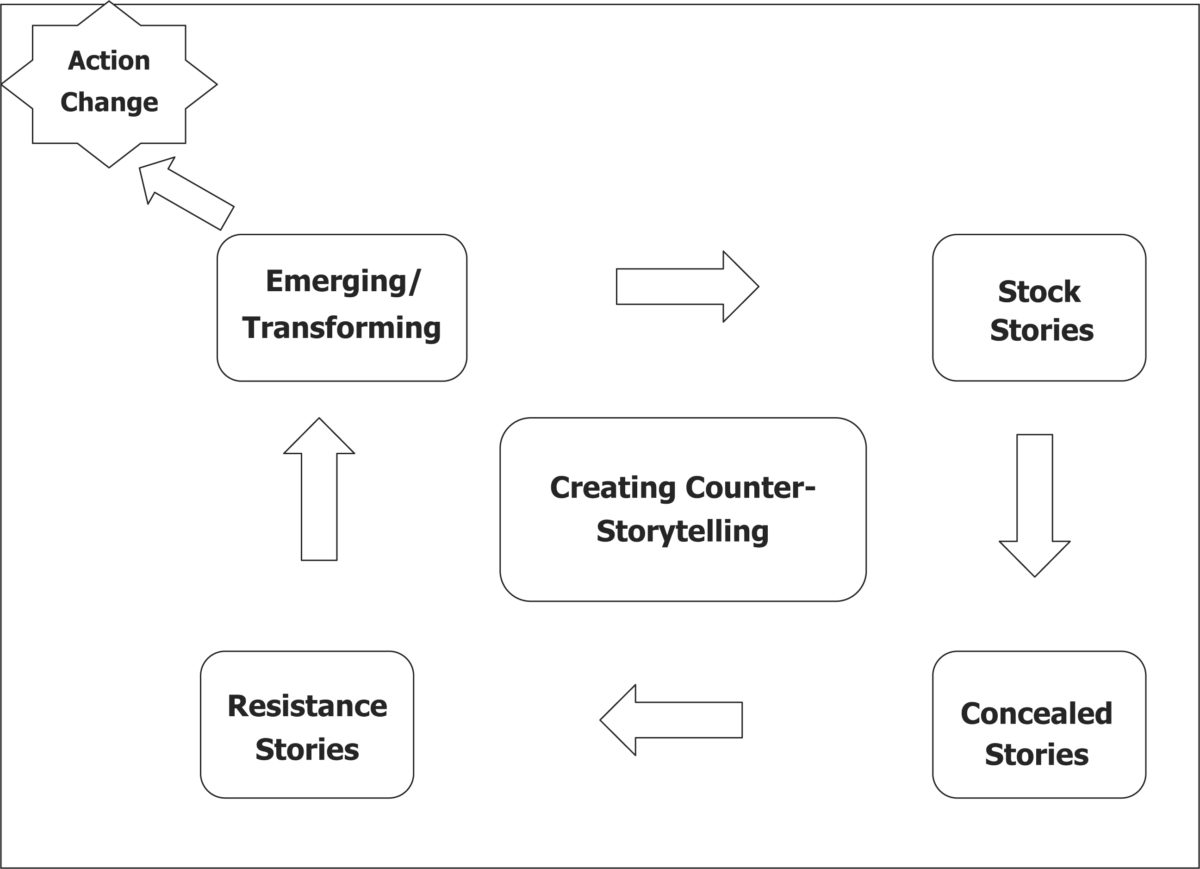

The Storytelling Project Model categorizes and describes four types of stories: (1) stock stories, (2) concealed stories, (3) resistance stories, and (4) emerging/transforming stories. According to Bell, the four story types are “connected and mutually reinforcing. Each story type leads into the next in a cycle that fills out and expands our understanding of and ability to creatively challenge racism. The story types provide language and a framework for making sense of race and racism through exploring the genealogy of racism and the social stories that generate and reproduce it…”

Each of the four types of story, when used in classrooms or dialogues, can “provide a way to engage body, heart, and mind to open up learning and develop a critical perspective that affords a broader understanding of cultural patterns and practices. Sensory engagement [through narrative and storytelling] without a way to critique social patterns may lead to a myopic focus on individual change that is at best anemic, but intellectual insight into broad patterns without sensory engagement can ultimately be distancing and disempowering.”

In short, stories can help students and dialogue participants engage with issues of race both emotionally and intellectually, and they can connect the lived experiences of racism with the customs, concepts, and policies that perpetuate inequitable or unjust social and political systems. Bell considers the last three story types—concealed, resistance, and emerging/transforming stories—to be “counter-stories” that challenge the mythmaking and historical revisionism of stock stories.

The Storytelling Project Model’s four types of stories:

1. Stock Stories

Stock stories are “the tales told by the dominant group, passed on through historical and literary documents, and celebrated through public rituals, law, the arts, education, and media” that “explain racial dynamics in ways that support the status quo” and “legitimize the perspective of the dominant white racial group in our society.” According to Bell, “Because stock stories tell a great deal about what a society considers important and meaningful, they provide a useful starting point for analyzing how racism operates to valorize and advantage the dominant white group.” In the United States, stock stories often built around the concepts of individualism, meritocracy, and progress, and they tend to pass as unquestioned truth when they are repeated in conversations, textbooks, speeches, articles, or films. A few examples of stock stories:

- America is a land of opportunity.

- Everyone who works hard can achieve the American dream.

- America has made a lot of progress on race.

- America is a colorblind society.

- Slavery happened a long time ago.

While these stock stories make explicit claims about the American experience that often blend historical facts with national mythmaking, they also carry implicit meanings that serve to overwrite American history and obscure the realities of living in an unequal society:

- America is a land of opportunity (therefore if someone doesn’t succeed, it’s their fault).

- Everyone who works hard can achieve the American dream (therefore if someone fails, they must be lazy or irresponsible).

- America has made a lot of progress on race (therefore we don’t need to be concerned about racism anymore; it’s no longer a significant problem).

- America is now a colorblind/post-racial society (therefore people of color should not be complaining about racism anymore).

- Slavery happened a long time ago (therefore people today should not be blamed for the problems of racism, and it’s not their responsibility to fix them).

Bell provides examples of specific stock stories that are widely circulated in American culture:

- “With rare exceptions, we learn to uncritically view the founding fathers as wise visionaries, and the Constitution as an ideal document. We typically do not learn about race-based decisions that explicitly enshrine race, as well as gender, privilege in founding documents created by an all-white, male, land-owning group.”

- “We generally study slavery as a dark, but singular, episode in our past. We do not learn that slavery or legal segregation have been in place for almost 90 percent of our history as a nation and that the vestiges of this history persist in patterns of racism today.”

- “The happy stock story taught to school children that Native Americans welcomed the Pilgrims (the Thanksgiving stock story) has in some cases been modified to acknowledge that vast numbers of Native people were killed and their land stolen by Whites. Yet the realities of the lives of Native American Indians today, even the fact of their contemporary existence, remain invisible, locked in stereotyped images of the past, with no exploration of ongoing white complicity and responsibility for their situation today.”

The Storytelling Project Curriculum offers a set of guiding questions that can be used in facilitated discussions about stock stories:

- What are the stock stories about race and racism that operate in U.S. society to justify and perpetuate an unequal status quo?

- How do we learn these stories?

- Who benefits from stock stories and who pays?

- How are these costs and benefits obscured through stock stories?

2. Concealed Stories

Concealed stories “are stories about racial experience eclipsed by stock stories that colonize the limelight.” As Bell writes, “While stock stories offer the sanitized official version at the center of public life, concealed stories embody the teeming, unruly, and contradictory stories that leak out from the margins…. While stock stories control mainstream discourse and naturalize white racial dominance, concealed stories narrate the ways that race differentially shapes life experiences and opportunities, disputing the unblemished tales of color-blindness, opportunity, and laudatory progress propagated by stock stories.”

The term concealed refers to stories “that are just beneath the surface; not so much unknown as constantly overshadowed, pushed back into the margins, and conveniently ‘forgotten’ or repressed. Like unwelcome company, concealed stories disconcert stock stories, challenging their smug complacency and assumed normality by insisting on a different accounting of experience. Through alternative renderings of the lived experience of racial subordination and racial advantage, concealed stories present a more encompassing view of reality, one that exposes the partiality and self-interest in stock stories. Concealed stories challenge stock stories by offering different accounts of and explanations for social relations.”

Bell provides several examples that illustrate different types of concealed stories:

- “Concealed stories by people of color tell about how racism is experienced by those subjected to racism and, for reasons of safety and survival, are often told outside of the hearing of the dominant group.”

- Concealed stories “are embodied in the everyday talk of people on the margins as they articulate their experiences, the challenges they face, the struggles to make it, and their aspirations and despairs living with the burdens of racism.”

- Concealed stories “catalogue ‘community cultural wealth,’ the strengths, capacities, and resilience within marginalized communities that are invisible, ignored, or trivialized in stock stories.”

- Concealed stories “creatively express the trauma of being dehumanized by racism as well as the hard-won knowledge, wisdom, and strength to carry on in the face of injustice.”

- Concealed stories “can also be discovered in the stories of white people who have become conscious of racism’s effects and expose how whiteness is taught and learned as an ideology of dominance…revealing how racism is learned and reinforced within white communities, thus exposing from the inside the dynamics of how privilege is reproduced.”

- Concealed stories told by white people also “subvert norms of complicity with business as usual and open the way for white people to create more inclusive and authentic relationships with people of color, relationships that can sustain alliances to work against racism.”

- Concealed stories “enable people of all racial groups to develop a more critical awareness about how racism operates so as to more consciously challenge its grip on our relationships and social structures.”

Guiding questions from the Storytelling Project Curriculum that can be used in facilitated discussions about concealed stories:

- What are the stories about race and racism that we don’t hear?

- Why don’t we hear them?

- How are such stories lost/left out?

- How do we recover these stories?

- What do these stories teach us about racism that the stock stories do not?

3. Resistance Stories

Resistance stories “narrate the persistent and ingenious ways people, both ordinary and famous, resist racism and challenge stock stories that support it in order to fight for more equal and inclusive social arrangements,” writes Bell. “They draw from a cultural/historical repository of narratives by and about people and groups who have challenged racism and injustice; stories we can learn from and build on to challenge stock stories we encounter today…. By illustrating antiracist perspectives and practices, resistance stories expand our vision of what is possible and form the foundation for ongoing creation of new stories that can inspire and direct antiracism work in the present.”

According to Bell, “Resistance stories, as a heritage of collective struggle to which we can lay claim in the present, are too seldom taught (often remaining as concealed stories that need to be unearthed and reclaimed). Yet they have the potential to inspire and mobilize people to see themselves as proactive agents and participants in democratic life. Such stories have the capacity to instruct and educate, arouse participation and collective energy, insert into the public arena and validate the experiences and goals of people who have been marginalized, and model skills and strategies for effectively confronting racism and other forms of inequality.”

Bell offers useful examples of how resistance stories can challenge stock stories:

- Even when resistance stories are told in mainstream culture, Bell writes, “they too often focus on iconic stories about heroic individuals; stories that obscure and sanitize the collective struggles that drive social change, and thus fail to pass on necessary lessons about how such change actually comes about. The Rosa Parks story is one example. In the typical mainstream story, Parks is most often presented as a woman who one day was simply too tired to stand and courageously refused to move to the back of the bus. The full story of Rosa Parks and the Montgomery bus boycott, however, is one of careful and organized planning over time by a group of people committed to challenging segregation.”

- “As counter-stories to the status quo, resistance stories (like concealed stories) challenge stock stories that reinforce power relations by bending resistance to suit their own ends,” writes Bell. “For example, resistance when framed in opposition to British domination in the Revolutionary War serves as a foundational story about the American spirit of independence and drive for freedom, a story that is preserved and passed on in textbooks, movies, and public rituals. Yet, Native American resistance to the domination by those same colonists is characterized as savage, hostile, and legitimately to be subjugated. When people of color resist the oppressive authority of the dominant white racial group, resistance is often characterized as negative, angry, inappropriate, something requiring suppression and subjugation. The lessons of resistance in our history as a nation are plentiful but too often hidden under the crust of official stock stories that serve the interests of the status quo. Yet, resistance stories are there to be resurrected and used to inspire people today, and indeed offer ways to make history relevant and meaningful to the present.”

Guiding questions from the Storytelling Project Curriculum that can be used in facilitated discussions about resistance stories:

- What stories exist (historical or contemporary) that serve as examples of resistance?

- What role does resistance play in challenging the stock stories about racism?

- What can we learn about anti-racist action by looking at these stories?

4. Emerging/Transforming Stories

Emerging/transforming stories are “new stories we construct to challenge stock stories, build on and amplify concealed and resistance stories, and take up the mantle of antiracism and social-justice work through generating new stories to catalyze contemporary action against racism,” writes Bell. “Such stories enact continuing critique and resistance to stock stories, subvert taken-for-granted racial patterns, and enable imagination of new possibilities for inclusive community.” Counter-stories develop when people discuss and analyze the larger cultural dynamics of stock, concealed, and resistance stories. What emerges from these story-based dialogues is a transformed understanding of oneself and others, and how systems of bias, prejudice, and discrimination can be challenged and rebuilt.

Bell shares several examples of emerging and transforming stories told by students and teachers who participated in dialogues based on the Storytelling Project Model:

- “There is no ‘neutral’ story, as stories by their very nature are full of perspective and personal experience, which makes them all the richer as models for learning. Too often I feel that curricula attempt to erase their inescapable political foundations and biases, instead of using these explicitly to encourage students to critically analyze and grow as thinkers.” —Student

- “The truth is that there is no such thing as an un-racialized situation…. The concealed story is that the color-blind mentality is detrimental to the goal of tolerance and equity… [T]o teach a child through your actions and words that race doesn’t matter is to belittle that child’s very being, and the identity they have created for themselves up to this point. In addition, ignoring any influence of race prevents you as a teacher from identifying and challenging institutional racism.” —Teacher

- “I realized I had fallen into the stock story that I was not a racist, that this was not my problem. I saw racism as something that I could help other people solve so they would not be discriminated against. I also hadn’t understood until then how race (specifically) and privilege (generally) affected my relationships with people on individual levels, and the kind of difficult community building that is needed is to lay these issues out on the table instead of only pretending they operated on some macro level, floating above our daily interactions.” —Student

- “Teaching resistance and counter-stories is much more than just asking higher order questions, though it is teaching students to examine and question their surroundings. It’s not watering down what you teach to token holidays but rather addressing the realities of the world and all of the difficult issues in it, such as racism, sexism, poverty, and violence, and giving students the ability to actively make changes through social action projects. It’s helping them realize that the society in which they live is not set in stone but rather shaped by the policies and people in it, and that they have the power to effect change. Resistance and counter-stories can provide powerful examples of how this has happened in the past and serve as a model for what can be done now.” —Teacher

Guiding questions from the Storytelling Project Curriculum that can be used in facilitated discussions about emerging and transforming stories:

- What can we draw from resistance stories to create new stories about possibilities for human community where differences are valued?

- What kinds of communities based on justice can we imagine and then work to embody?

- What kinds of stories can raise our consciousness and support our ability to speak out and act where instances of racism occur?

In summary, Bell writes that the “four story types are intricately connected. Stock stories and concealed stories are in effect two sides of the same coin, reflecting on the same ‘realities’ of social life, but from different perspectives. Resistance and counter stories are also linked through their capacity to challenge the stock stories. Resistance stories become the base upon which counter stories can be imagined and serve to energize their creation. Counter stories then build anew in each generation as they engage with the struggles before them and learn from and build on the resistance stories that preceded them.”

Acknowledgments

Organizing Engagement thanks Lee Anne Bell for her contributions to improving this introduction and for permission to republish excerpts and an image from Storytelling for Social Justice: Connecting Narrative and the Arts in Antiracist Teaching.

References

Bell, L. A. (2019). Storytelling for Social Justice: Connecting Narrative and the Arts in Antiracist Teaching. New York, NY: Routledge.

Creative Commons

This work by Organizing Engagement is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. When excerpting, adapting, or republishing content from this resource, users should cite the source texts and confirm that all quotations and excerpts are accurately presented.